Retinoids, Antibiotics, and Benzoyl Peroxide Top the List

The Essential Info

The 5 most frequently prescribed acne medications are:

- Tretinoin – topical retinoid

- Isotretinoin* – oral retinoid

- Minocycline – oral antibiotic

- Benzoyl Peroxide – topical antibacterial that also unclogs pores

- Doxycycline – oral antibiotic

*Isotretinoin comes with severe and potentially lifelong side effects, and is only approved for use in people with severe and scarring acne that does not respond to other treatments. However, because of its effectiveness, doctors sometimes controversially prescribe it for milder acne as well.

Be Your Own Advocate: To avoid a medication merry-go-round, do your own research in order to understand your options. Don’t simply accept any prescription your doctor advises. Arm yourself with knowledge on the available options, and ask questions. And make sure you are speaking to a dermatologist who is an expert in acne.

The Science

Several studies have looked into the question of which prescriptions are most common for acne. The most recent data comes from a 2023 study that analyzed more than 30 million patient visits to the doctor between 1993 and 2016 in the US.1 According to that comprehensive study, the top 5 medications doctors prescribed for acne during that time were:

- Tretinoin – a topical retinoid

- Isotretinoin – an oral retinoid

- Minocycline – an oral antibiotic

- Benzoyl peroxide – a topical antibacterial that also unclogs pores

- Doxycycline – an oral antibiotic

As we can see from the study, doctors frequently prescribe antibiotics for acne, despite significant drawbacks and underwhelming results. I’ll discuss this more later in this article.

In this article, we will discuss in more detail the top 5 most commonly prescribed medications.

The 5 Most Commonly Prescribed Acne Medications

1. Tretinoin

Despite providing only moderate benefit to acne, tretinoin is the single most frequently prescribed acne medication. Various treatment guidelines, such as those recommended by the American Academy of Dermatology, consider topical (applied to the skin) retinoids, such as tretinoin, to be the preferred treatment for acne, except in severe cases. Many guidelines continue to recommend topical retinoids as the first choice of treatment for mild-to-moderate acne. However, it should be noted that since retinoids like tretinoin only produce partial clearing of acne, they are almost always prescribed alongside other treatments.

Tretinoin has been one of the primary acne treatments for over 40 years, largely because of its ability to:

- Help skin cells shed, thus keeping the skin turning over properly and preventing clogged pores

- Treat mild acne lesions as well as papules and pustules, which are inflamed “pimples” or “zits,” when used in combination with other medications

- Reduce skin inflammation

- Prevent acne-induced scarring

- Prevent disease progression – in other words, preventing acne from getting worse3

The following research from the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, American Journal of Clinical Dermatology, and Journal of Dermatological Treatment speak about how retinoids help unclog pores, and can help clear acne when used alongside other medications.

Expand to read details of research

The American Academy of Dermatology’s guidelines of 2016, published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, states, “Retinoids are the core of topical therapy for acne because they [open clogged pores], resolve the precursor microcomedone lesion, and are antiinflammatory. These agents enhance any topical acne regimen and allow for maintenance of clearance after discontinuation of oral therapy. Retinoids are ideal for comedonal acne and, when used in combination with other agents, for all acne variants.”2

A 2003 article in the American Journal of Clinical Dermatology notes, “Preclinical data suggest that topical retinoids and retinoid analogs may also have direct anti-inflammatory effects. A wealth of clinical data confirms that topical retinoids and retinoid analogs significantly reduce inflammatory lesions.”3

Despite the fact that dermatologists consider topical retinoids to be the preferred therapy for acne, and the fact that guidelines have recommended since 2003 that all patients who have mild-to-moderate acne be treated with a topical retinoid, a 2013 study in the Journal of Dermatological Treatment found that doctors prescribed topical retinoids to only 40% of patients. This study also found that doctors were more likely to prescribe a topical retinoid to young patients and also to female patients, regardless of their age. The authors noted, “Based on the strong clinical evidence, acne management guidelines have recommended since 2003 that almost all acne patients should be treated with a topical retinoid except for those with the most severe cases. Nevertheless, according to our findings from the most recent data available, the frequency of topical retinoid use for acne vulgaris remains low.”4

2. Isotretinoin

Isotretinoin, often known by its brand name Accutane®, is the second-most prescribed acne medication. It is a highly effective oral medication which typically is only approved for the most severe cases of acne. Patients take isotretinoin usually for 15 – 20 weeks, and in that time it successfully shrinks skin oil glands, usually permanently. Because of its long-lasting effects, it can offer long-term relief from acne symptoms in the majority of people who take an adequate dosage. In 14.6 to 52% of people, acne returns to some degree after isotretinoin treatment, but often the acne that comes back is less severe than before treatment.

Because of isotretinoin’s effectiveness, doctors increasingly prescribe it for mild-to-moderate acne as well. This practice is highly controversial because isotretinoin is such a powerful medication that it can cause severe birth defects if a patient takes it when pregnant. It also can cause severe, sometimes long-term, side effects. The FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration) recommends isotretinoin only for severe nodular acne.

3. Minocycline

Minocycline is the third most commonly prescribed acne medication. It is an oral antibiotic that belongs to the class of antibiotics known as tetracyclines, which are the most widely prescribed oral antibiotics for acne because of their effectiveness against acne bacteria and their anti-inflammatory effects.

Antibiotics, whether topical or oral, should only be used for a maximum of 3 months. The reason for these restrictions is that bacteria can become resistant to antibiotics over time. Furthermore, antibiotics do not work for everyone. When they do work, they only provide moderate benefit, and can come with many side effects, particularly gastrointestinal discomfort.

Minocycline is prescribed more often than other oral antibiotics because, as is discussed in the following 2011 article in The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology, it may accumulate more in the skin, providing for better acne-killing properties and lowered risk of creating resistant bacteria. In addition, it may be better absorbed in the gut and have less food interactions compared with other oral tetracyclines. On the downside, it comes with more side effects, so doctors often prescribe the extended-release form of minocycline to reduce these unwanted effects.

A 2011 article in The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology found that minocycline accumulated in skin tissue in significantly greater amounts than did other tetracyclines. It also noted that in a 6-week study comparing minocycline to other tetracyclines, minocycline decreased acne bacteria levels 10 times more than did the other tetracyclines, the reduction in acne bacteria persisting 3 weeks after the course of treatment. These results may be due to minocycline’s enhanced ability to penetrate skin tissue, thereby reducing the development of resistant bacteria. The authors noted, “Minocycline treatment may have an advantage compared with tetracycline or doxycycline because enhanced tissue penetration may be accompanied by a lower incidence of emergence of resistant [acne bacteria] strains.”5

The same article described another study that tested antibiotic resistance in 73 strains of acne bacteria. Compared to other antibiotics, minocycline was the only one that effectively targeted all 73 strains. This result demonstrates that minocycline is effective against most antibiotic-resistant strains of acne bacteria, which increases its viability.5

Minocycline possesses other characteristics that make it better than other oral antibiotics:

- It is absorbed into the gastrointestinal tract better than other oral antibiotics, which increases the amount of medication available.

- It doesn’t interact with as many foods as other oral antibiotics.

4. Benzoyl Peroxide

Benzoyl peroxide is a mainstay of acne treatment and works by quickly and almost completely killing acne bacteria as well as drying the skin and shedding skin cells, thus keeping pores from becoming clogged. It is available by prescription in up to 10% strength. It is also available in this same strength over-the-counter. One benefit of benzoyl peroxide is that bacteria cannot become resistant to it. Thus, it is not surprising that dermatologists frequently prescribe benzoyl peroxide for acne.

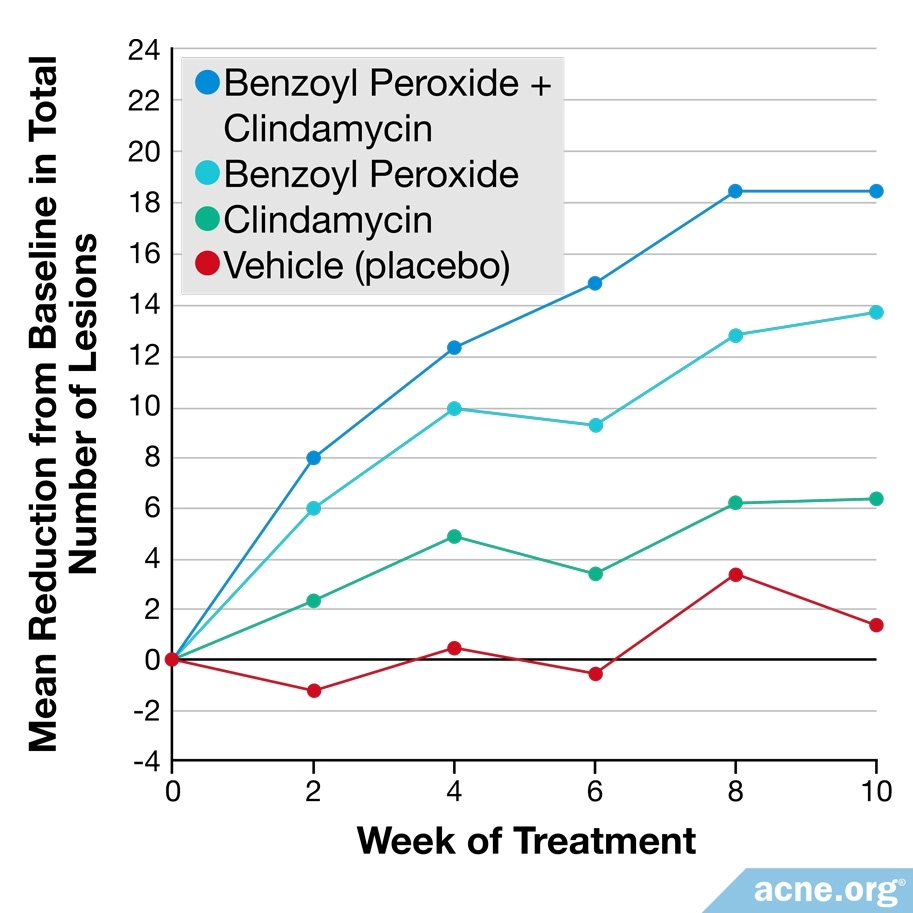

While benzoyl peroxide is a popular acne-fighting medication on its own, it is sometimes prescribed in combination with other medications, such as topical retinoids or topical antibiotics.6 These combinations tend to have slightly higher efficacy than benzoyl peroxide by itself.

5. Doxycycline

Doxycycline is an oral antibiotic that kills acne bacteria and also reduces inflammation. Like other antibiotics, it should only be taken for a maximum of 3 months. Doxycycline only works moderately well and only in some people, and it has a relatively high chance of producing side effects. Nonetheless, it is in the top 5 most-prescribed acne medications because it tends to help with severe acne, at least in the short term.

Why is doxycyline still prescribed when minocycline has been shown to work better for acne? This is because doxycycline often has a lower incidence of serious side effects, lower chance of photosensitivity (sunburn), and also sometimes just because it is more widely available across the globe.

Prescribing Practices Change Gradually Over Time

Past medical records suggest that prescribing practices for acne medications have been slowly changing over the past few decades. Data collected since 1993 reveals 2 interesting observations:

- Tretinoin has consistently been the most frequently prescribed acne medication for at least 27 years.

- In recent years, experts have been urging doctors to limit antibiotic prescriptions, including those for acne. Widespread use of antibiotics increases the chances of bacteria developing antibiotic resistance, which can ultimately result in a global health crisis when antibiotics stop working against bacterial infections altogether. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has begun a campaign to educate medical professionals about when it is appropriate to prescribe antibiotics. Both the CDC and the World Health Organization (WHO) also organize an annual Antibiotic Awareness Week to draw attention to the problem of excessive antibiotic use.7-9 Although doctors have been slow to adopt the new guidelines,10 we are likely to see a decline in antibiotic prescriptions for acne in the future.

References

- Perche, P. O., Peck, G. M., Robinson, L., Grada, A., Fleischer, A. B. Jr. & Feldman, S. R. Prescribing trends for acne vulgaris visits in the United States. Antibiotics (Basel) 12, 269-277. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36830180/

- Zaenglein, A. et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2016). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26897386

- Millikan, L. The rationale for using a topical retinoid for inflammatory acne. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology 4, 75 – 80 (2003). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12553848

- Tan, X. et al. Factors associated with topical retinoid prescriptions for acne. Journal of Dermatological Treatment 25, 110 – 114 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23802699

- Leyden, J. & Del Rosso, J. Oral antibiotic therapy for acne vulgaris: Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic perspectives. The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology 4, 40 – 47 (2011). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21386956

- Leyden, J. et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of a combination topical gel formulation of benzoyl peroxide and clindamycin with benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin and vehicle gel in the treatments of acne vulgaris. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology 2, 33 – 39 (2001). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11702619

- Del Rosso, J. Q., Webster, G. F., Rosen, T. et al. Status report from the scientific panel on antibiotic use in dermatology of the American Acne and Rosacea Society: Part 1: Antibiotic prescribing patterns, sources of antibiotic exposure, antibiotic consumption and emergence of antibiotic resistance, impact of alterations in antibiotic prescribing, and clinical sequelae of antibiotic use. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 9, 18‐24 (2016). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4898580/

- King, L. M., Fleming-Dutra, K. E. & Hicks, L. A. Advances in optimizing the prescription of antibiotics in outpatient settings. BMJ 363, k3047 (2018). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6511972/

- Dessinioti, C. & Katsambas, A. Antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance in acne: Epidemiological trends and clinical practice considerations. Yale J Biol Med 95, 429-443 (2022). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36568833/

- Hoover, W. et al. Topical antibiotic monotherapy prescribing practices in acne vulgaris. Journal of Dermatological Treatment 25, 97 – 99 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24171409

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products