Treating Acne in Black Skin

The Essential Info

As with all ethnicities, acne is common in black skin.

Like any non-Caucasian ethnicity, Black people also experience more hyperpigmentation (dark/red spots left behind after an acne lesion heals).

Black people also tend to have more of an issue with raised/keloid scarring.

Treatment for acne is more or less the same regardless of skin color, but people with darker skin should ask more questions if they embark upon laser therapy, chemical peels, or photodynamic therapy, all of which can cause pigmentation changes after the procedure.

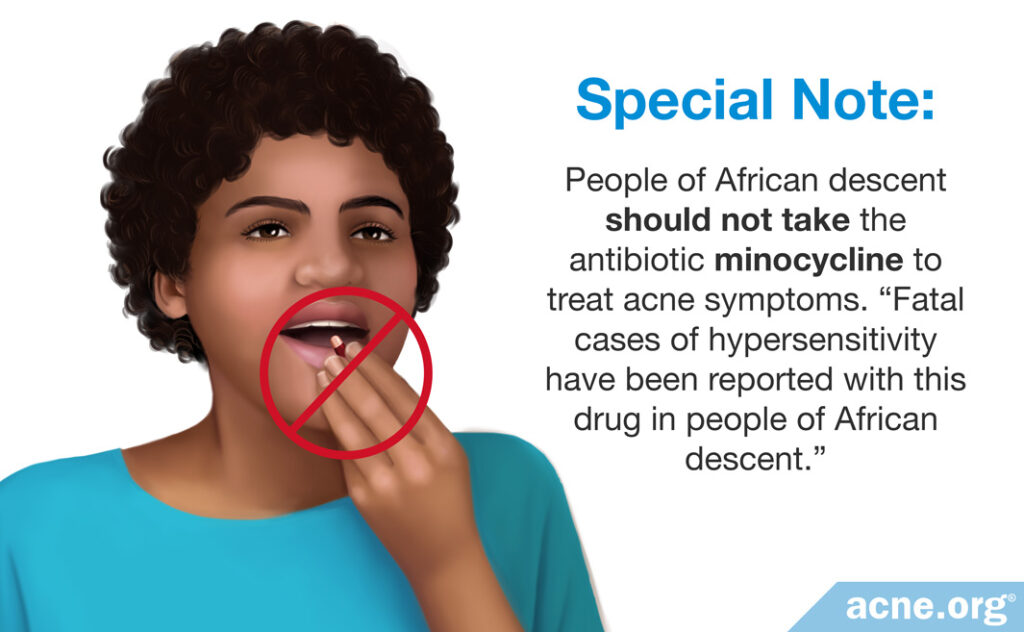

Finally, people of African descent should not take the oral antibiotic minocycline, which is the most prescribed oral antibiotic for acne, because it can cause “fatal cases of hypersensitivity.”

The Science

Overview

Acne is the most common skin disorder in black adolescents and black adults and is often the primary reason for a visit to a doctor or dermatologist, according to several studies.1-7

Expand to read details of studies

According to the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, “Acne vulgaris is an extremely common dermatological problem in Africans and people of African descent worldwide.”4 Acne is also the most common skin disease in people with black skin in the United States.5

From 2007 to 2018, acne was the most common reason for black African Americans to visit dermatologists, as reported in the Southern Medical Journal.6

In 2007, the medical journal Cutis published a study that included 1412 patients from the Skin of Color Center at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center in New York. According to this study, the most common diagnosis for Black patients was acne.7

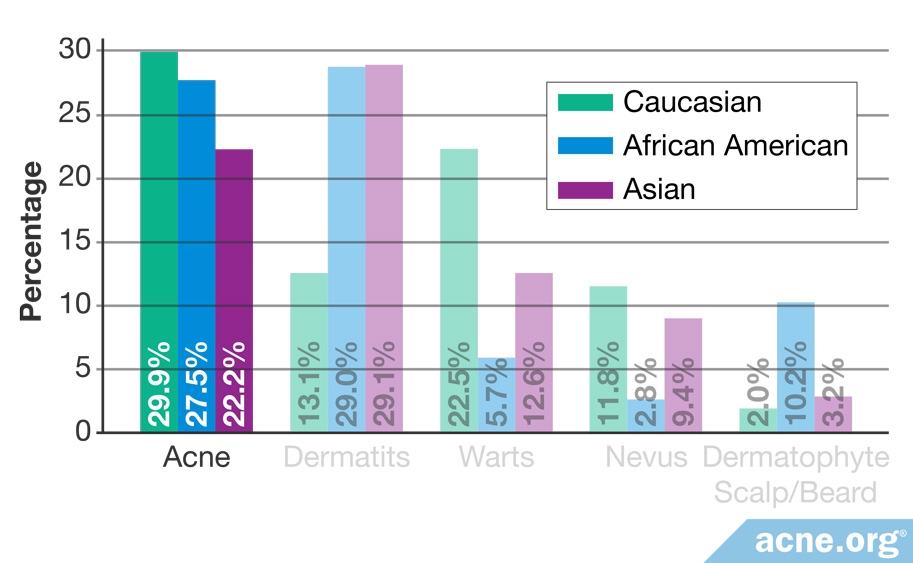

One recent study found that Black adolescents experience slightly less acne than White adolescents, but slightly more than Asian adolescents.8

Expand to read details of study

A 2012 study published in Pediatric Dermatology found that African American adolescents suffer with acne at a slightly higher rate when compared to Asian American adolescents and a slightly lower rate when compared to Caucasian American adolescents.8

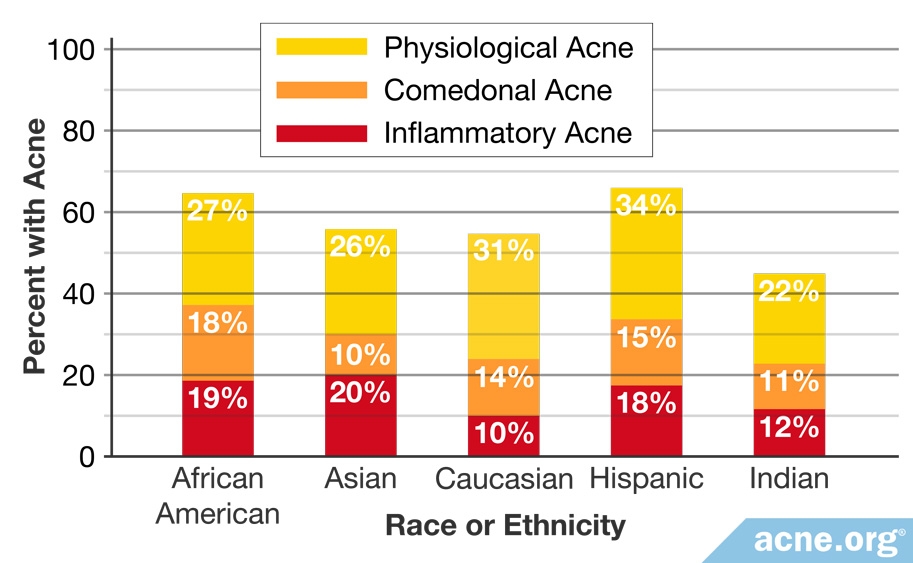

Another study looked at acne in women of all ages, and found that women of African descent experience more acne overall than any other ethnic group except Hispanic women.9

Expand to read details of study

Another study published in 2011 in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology researched women of all ages, and showed a higher level of acne in women of African descent when compared to Caucasians, Asians, or Indians, with only Hispanics showing overall higher levels. When looking specifically at what researchers deemed “clinical acne,” another term for the usual acne people experience during adolescence with clogged pores (non-inflammatory acne) and inflamed lesions (inflammatory acne), women of African descent had the highest levels of any subgroup. “Physiologic” acne, or acne which tends to show up in adult women and tends to be less severe, was also higher in women of African descent than in any other subgroup except for Hispanic women.9 What is clear is that there is a high prevalence of acne in people of African descent. Unfortunately, relatively few acne-related studies have been conducted specifically on people with black skin.

So when it comes to how much acne Black people get compared to other ethnicities, while it might be true that Black adolescents land somewhere in the middle, and Black women might experience a bit more acne, it is impossible to confidently know the real story with the amount of data we have so far. Suffice it to say that acne is a real and serious problem for Black people.

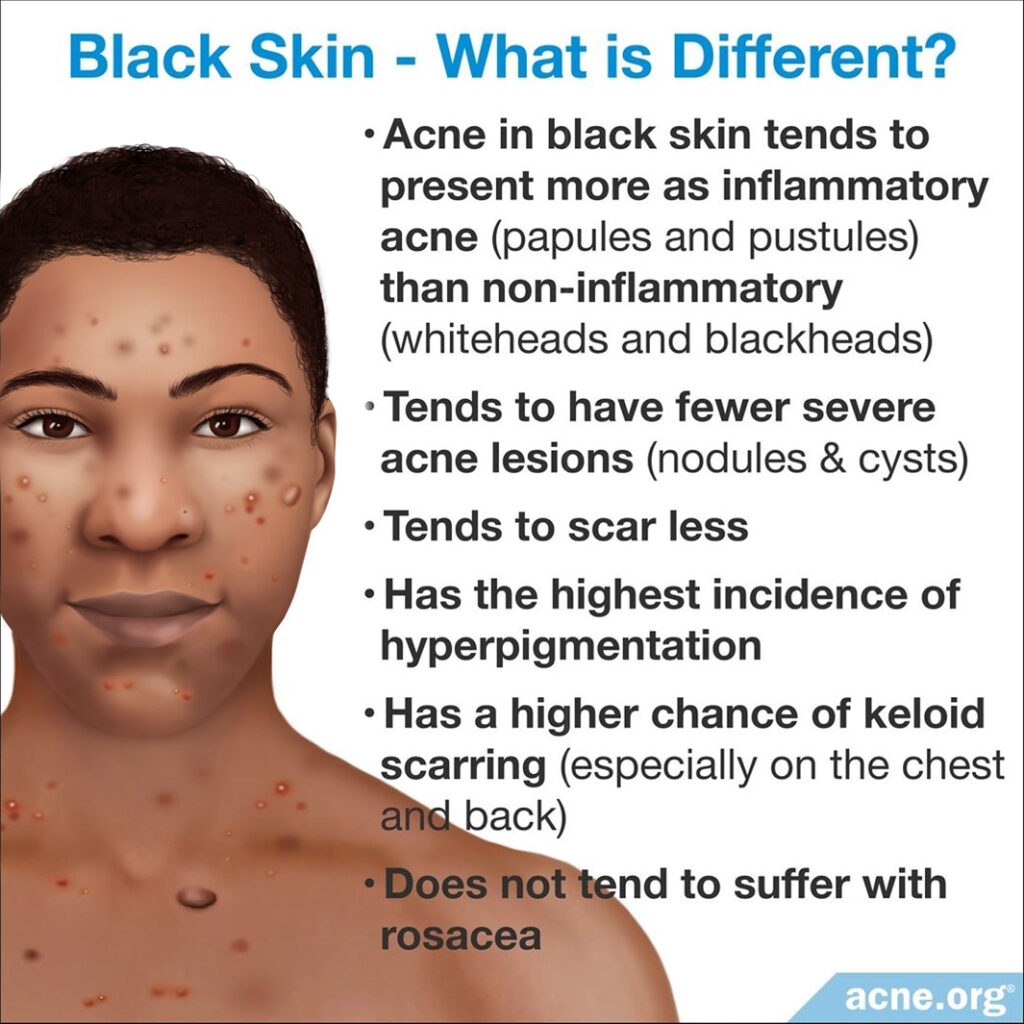

What Is Different about Black Skin

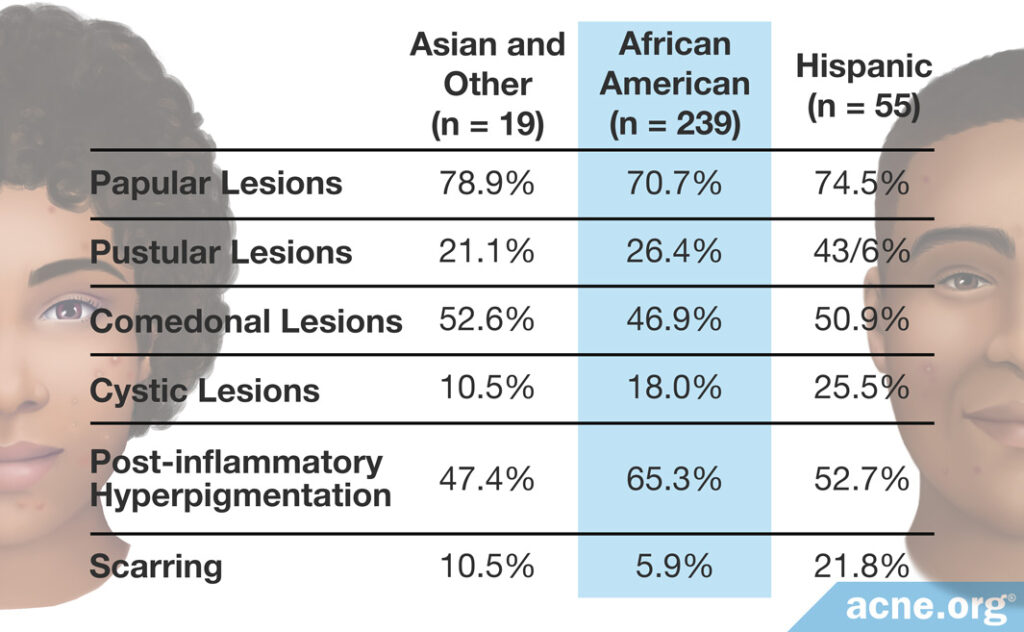

People with black skin tend to experience what is referred to as inflammatory acne–the most common type of acne that comes with lesions that are red and sore. This is actually good news because inflammatory acne can be easier to treat than non-inflammatory acne, which includes lesions that are neither red nor sore, like whiteheads and stubborn blackheads.

Black people also tend to have fewer severe acne lesions (nodules and cysts), which are most prone to scarring. For this reason, Black people tend to have less scarring overall compared to other ethnicities.10

Despite the fact that people of African descent tend to develop less severe lesions, when scarring does occur, it can come with a particularly vicious type of scar called a keloid scar that is raised above the skin instead of being indented in the skin. These keloid scars are most common on the chest and back and are extremely resistant to scar revision procedures.11 This is why effective acne prevention is paramount when it comes to black skin, particularly preventing body acne.

Next, while all non-Caucasian skin types tend to have a higher incidence of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, a medical term for marks left after acne goes away, from the research we have thus far, people of African descent have the greatest incidence of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation.10

Picking at the skin can make these marks worse, so people with darker skin types are strongly urged to avoid picking.

Dermatologists often remark on how their Black patients consider these marks worse than the acne itself.2,10-13

A study published in 2011 in The Journal of Dermatology (see table below) has shown that these marks are very common in black skin and last much longer than acne itself.5 The authors state, “These data confirmed that hyperpigmentation as a consequence of acne is a much more important problem for patients with skin of color than for white ones…The hyperpigmentation persists for months to years: much longer than the acne lesions themselves.”5

Because black skin is more prone to hyperpigmentation, Black people should exercise extra caution when considering acne treatments like laser therapy, chemical peels, or photodynamic therapy, all of which can cause pigmentation changes after the procedure.

Finally, people of African heritage do not tend to suffer with rosacea, which is not acne, but is another skin condition that is sometimes confused with acne.12

How to Treat Acne in Black Skin

Acne develops and is treated the same way regardless of skin color. There are several options including topical treatment as well as Accutane (isotretinoin) for people with severe, widespread, and scarring acne.

According to the International Journal of Dermatology, “benzoyl peroxide is particularly effective for the inflammatory component.” Benzoyl peroxide is a mild drying and peeling agent, but people with black skin tend to have less flakiness and scaling of the skin and tolerate it well.16,17

What is most important is to treat acne early and aggressively, since black skin is prone to hyperpigmentation and keloid scarring.18 Choose a treatment regimen that avoids irritating the skin, since skin irritation can itself trigger or worsen hyperpigmentation.19

Black Hair Products – A Special Concern: Black people sometimes use pomade and/or skin oil to relax the hair. These products can contain pore-clogging ingredients and can cause acne around the hairline.

Ingrown Hairs – Another Special Concern: Black men are far more susceptible to ingrown hairs on the neck when shaving. Ingrown hairs are not acne, but can look like acne.

Minocycline – Caution: Because of the potential for hypersensitivity, Black people should not take minocycline, an antibiotic that is sometimes prescribed for acne.

References

- Dunwell, P. & Rose, A. Study of the skin disease spectrum occurring in an Afro-Caribbean population. Int. J. Dermatol. 42, 287 – 289 (2003). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01358.x

- Alexis, A. F. & Lamb, A. Concomitant therapy for acne in patients with skin of color: a case-based approach. Dermatol. Nurs. 21, 33 – 36 (2009). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19283960

- Yahya, H. Acne vulgaris in Nigerian adolescents–prevalence, severity, beliefs, perceptions, and practices. Int. J. Dermatol. 48, 498 – 505 (2009). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19416381

- Jacyk, W. K. Adapalene in the treatment of African patients. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 15 Suppl 3, 37 – 42 (2001). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11843232

- Morrone, A. et. al. Clinical features of acne vulgaris in 444 patients with ethnic skin. J. Dermatol. 38, 405 – 408 (2011). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21544948

- Peck, G. M., et al. Reasons for visits to the dermatologist stratified by race. Southern Medical Journal 115, 780-783 (2022). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36191915/

- Alexis, A. F., et al. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis 80, 387-94 (2007). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18189024/

- Henderson, M. D. et. al. Skin-of-color epidemiology: a report of the most common skin conditions by race. Pediatr. Dermatol. 29, 584 – 589 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22639933

- Perkins, A. C., Cheng, C. E., Hillebrand, G. G., Miyamoto, K. & Kimball, A. B. Comparison of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris among Caucasian, Asian, Continental Indian and African American women. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 25, 1054 – 1060 (2011). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21108671

- Taylor, S. C., Cook-Bolden, F., Rahman, Z. & Strachan, D. Acne vulgaris in skin of color. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 46, S98 – 106 (2002). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11807471

- Frazier, W. T., et al. Common dermatologic conditions in skin of color. American Family Physician 107, 26-34 (2023). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36689965/

- Halder, R. M. & Nootheti, P. K. Ethnic skin disorders overview. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 48, S143 – 148 (2003). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12789168

- Shah, S. K. & Alexis, A. F. Acne in skin of color: practical approaches to treatment. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 21, 206 – 211 (2010). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20132053

- Davis, E. C. & Callender, V. D. A review of acne in ethnic skin: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and management strategies. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 3, 24 – 38 (2010). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20725545

- Bhate, K. & Williams, H. C. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br. J. Dermatol. 168, 474 – 485 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23210645

- Kane, A., Niang, S. O., Diagne, A. C., Ly, F. & Ndiaye, B. Epidemiologic, clinical, and therapeutic features of acne in Dakar, Senegal. Int. J. Dermatol. 46 Suppl 1, 36 – 38 (2007). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17919205

- Poli, F. Acne on pigmented skin. Int. J. Dermatol. 46 Suppl 1, 39 – 41 (2007). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17919206

- Yin, N. C. & McMichael, A. J. Acne in patients with skin of color: practical management. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 15, 7 – 16 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24190453

- Alexis, A. F., Harper, J. C., Stein Gold, L. F. & Tan, J. K. L. Treating Acne in Patients With Skin of Color. Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 37(3S), S71-S73 (2018). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30192346

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products