Excoriation Disorder, Also Called Skin Picking Disorder, Is a Psychiatric Disorder That Can Make Acne Worse

The Essential Info

Picking at the skin is one of the worst things someone with acne can do to their skin, because it:

- Delays healing: Acne lesions heal more slowly when they are picked.

- Causes physical irritation: Anything that physically irritates the skin may lead to more acne.

- Increases the chance of scarring: Dermatologists who specialize in acne scar revision often blame picking more for scarring than the acne itself.

In short, don’t pick!

However, sometimes just being told not to pick isn’t realistic. When picking becomes compulsive, at that point it gets a medical name: excoriation disorder. Medications and psychotherapy can help treat excoriation disorder, but results are mixed. If you find it difficult to stop picking at your acne lesions or other parts of your skin, talk to your doctor about finding a therapist who can help you.

The Science

- What Is Excoriation Disorder?

- How Does Excoriation Disorder Relate to Acne?

- How Common Is Excoriation Disorder?

- What Other Disorders Occur along with Excoriation Disorder?

- What Causes Excoriation Disorder?

- How Do You Treat Excoriation Disorder?

Q: What is the worst thing someone with acne can do to perpetuate the cycle of acne and cause it to scar?

A: Pick at their skin.

It’s as simple as that. Picking at the skin delays healing of acne lesions and causes rampant physical irritation to the skin. Anything that physically irritates the skin can make acne worse, so picking at existing lesions just creates more lesions, and a vicious cycle is born. Picking also dramatically increases the chances that acne will scar.

But sometimes, stopping picking is easier said than done. For some people, picking becomes compulsive, and at that point it gets a diagnosis of excoriation disorder. When it’s picking at acne lesions in particular, the diagnosis gets even more specific and is called acne excoriée.

If you can stop picking now, do it. If you can’t seem to be able to quit, read on as we will look more deeply into excoriation disorder and its connection to acne.

What Is Excoriation Disorder?

Excoriation disorder, also called skin picking disorder or dermatillomania, is a psychiatric disorder in which people repetitively and compulsively pick at their skin, causing tissue damage.

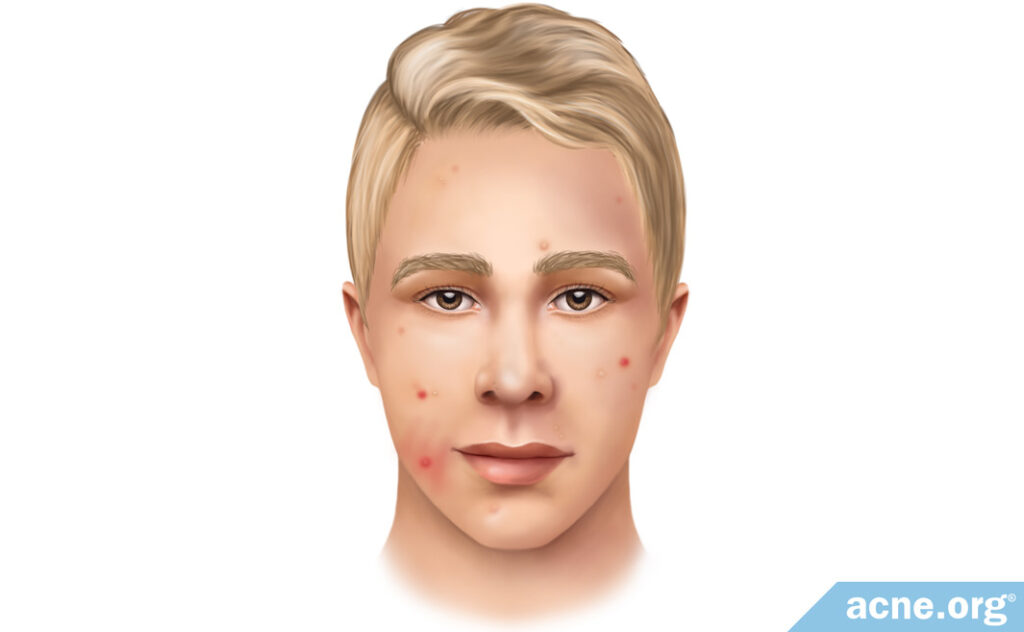

This skin picking is compulsive, meaning that people feel like they have to do it and they can’t stop even if they want to. People with excoriation disorder might pick at acne lesions, scabs, or other skin irregularities. When the picking is specifically on acne lesions, scientists refer to it as acne excoriée.1-4

Excoriation disorder has a connection to OCD in that people often feel powerless to stop and are highly distressed by it.4-6

Expand to see how the medical community describes it similarly to OCD

The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), which is the manual that the American Psychiatric Association uses to diagnose mental illnesses, classifies excoriation disorder under the heading of obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders. This is because excoriation disorder has a connection with the genetic predispositions and symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).4

A 2002 article in the journal Depression and Anxiety notes, “As is characteristic of obsessive-compulsive…spectrum disorders, patients acknowledge the self-inflicted nature of these lesions, and are distressed by their inability to control this behavior.”5

The DSM-5 gives the following criteria for a diagnosis of excoriation disorder:

- Recurrent skin picking that results in skin lesions.

- Repeated, unsuccessful attempts to decrease or stop skin picking.

- The skin picking causes clinically significant distress or impairment in important areas of functioning (such as functioning at work or in social situations).

- The skin picking cannot be attributed to the effects of a substance or another medical or mental condition.

- The skin picking cannot be better explained by the symptoms of another mental disorder (such as delusions or intentional non-suicidal self-injury).6

In addition to finding that skin picking has similarities to OCD, research also shows that some people who pick at their skin may be driven by feelings of disgust toward their appearance.7,8

Expand to read more about the connection between skin picking and disgust

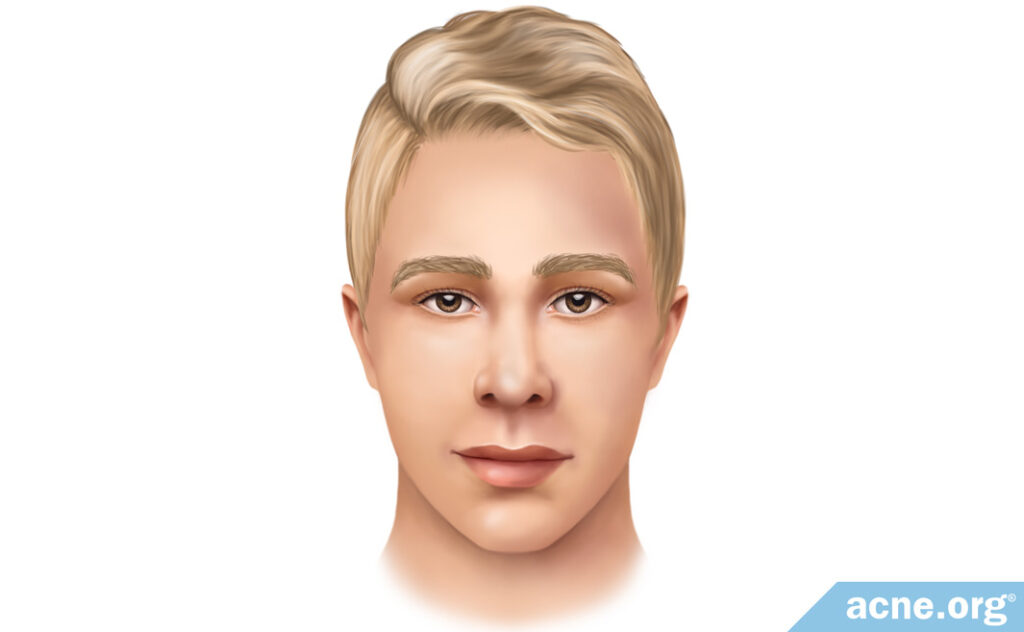

In a 2018 study published in the journal Brain Imaging and Behavior, researchers looked for a connection between skin picking and feelings of disgust. They showed participants with skin-picking disorder and without skin-picking disorder two types of images:

1. Images showing smooth skin

2. Images showing skin irregularities

The participants suffering from skin-picking disorder showed more disgust when looking at skin irregularities compared to participants without this disorder. In addition, the participants with skin-picking disorder felt an urge to pick at their skin when viewing images of imperfect skin, and their brains showed more activity in areas that process disgust compared to participants without skin-picking disorder.7

How Does Excoriation Disorder Relate to Acne?

When acne first begins, this is often the catalyst for the start of excoriation disorder. People with excoriation disorder do not just pick at acne lesions a bit and move on, however. The picking becomes compulsive and they continue picking even after the lesion clears.9

And as we have learned, this repetitive picking can physically irritate the skin and lead to more acne, leaving the person in a vicious cycle of acne and picking.10,11

According to a 2013 article in the British Journal of Dermatology, “A very small, observational study showed that picking at acne lesions worsened the inflammation and [pimples].”10

Skin lesions caused by picking in people with excoriation disorder can range from just a few in mild cases to hundreds in severe cases. Repeated picking at these lesions can result in significant tissue damage and even serious medical complications such as infections and septicemia, which is a life-threatening condition that results when an infection gets into the bloodstream.9

How Common Is Excoriation Disorder?

Excoriation disorder occurs in approximately 1% – 5% of the general population, though it tends to occur more often in people with other psychiatric disorders such as OCD, anxiety, depression, or eating disorders.1,6,9-12

It also tends to occur slightly more often in females than in males.1,4,12

What Other Disorders Occur along with Excoriation Disorder?

Excoriation disorder often occurs along with other psychiatric disorders. In particular, studies have reported that excoriation disorder occurs alongside:

- Body dysmorphic disorder

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder

- Trichotillomania (hair pulling disorder)

- Eating disorders

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Substance use disorders2,9,13-15

While scientists don’t know exactly why excoriation disorder often occurs with these other disorders, at least some of the overlap is probably because they share biological characteristics.2,13

What Causes Excoriation Disorder?

Researchers don’t know what causes excoriation disorder, but both biological and psychological factors appear to contribute to it.

- Biological factors likely include genetic predisposition. In other words, if your mom or dad was a “picker,” you are more likely to be one yourself. Studies back this up, with some studies showing that up to 43% of people with excoriation disorder may have inherited it from their parents. Twin studies have also shown a strong genetic component to excoriation disorder.9,16

Scientists have zeroed in on two different genes that may play a role in predisposing someone to develop excoriation disorder:

The first gene is called HOXB8, a gene that helps regulate the formation of organs and tissues in a developing fetus. At least one study has found that altering this gene in mice is associated with excessive grooming that leads to hair loss and skin lesions.

The second gene is called SAPAP3, a gene that helps brain cells communicate with each other. A study in mice demonstrated that mice that were lacking this gene engaged in compulsive grooming behaviors that led to bald patches and open sores. Another study looking at families with OCD found that a variation in this gene was associated with the development of grooming disorders such as nail biting.9

- Psychological factors might include attempts to avoid uncomfortable emotions or reduce obsessive thoughts, or impulsivity (the tendency to act on a whim, without thinking about it).9,17 To put it succinctly, someone might pick at their skin in a subconscious attempt to avoid thinking about the fact that they are unhappy.

How Do You Treat Excoriation Disorder?

Excoriation disorder can be treated with medications, with psychotherapy, or a combination of both. Sadly, research suggests that less than 20% of people suffering from excoriation disorder seek treatment. Without treatment, excoriation disorder is more likely to become chronic and can continue for decades.15,18

Treatment is also not a guarantee, as long-term results have been mixed and sometimes unimpressive.17 Let’s take a closer look at the available treatment options.

Medications

Medications that can treat excoriation disorder include:

- Antidepressants, especially SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) and TCAs (tricyclic antidepressants)

- Opiate antagonists, such as naltrexone

- Atypical antipsychotics, such as olanzapine3,4,17

Medications do not always work. When they do work, they can require patience. For example, antidepressants often take 2 to 6 weeks to start working.

Antidepressants, which are most commonly prescribed, can have unpleasant side effects such as nausea, diarrhea, significant weight gain, insomnia, sedation, and loss of libido.3

Finally, medications do not address psychological factors that may contribute to excoriation disorder. For this reason, medications should ideally be prescribed along with psychotherapy.17

Psychotherapy

There are several different psychotherapy approaches that can help with excoriation disorder:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT): Cognitive behavioral therapy involves learning to change problematic patterns of thinking and behavior. In CBT, therapists help their clients to first identify, then challenge, and then change their thoughts and behaviors related to skin picking.

- Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT): Acceptance and commitment therapy is a form of cognitive behavioral therapy that uses mindfulness, acceptance, and behavioral change strategies to reduce skin picking behavior. Clients learn to identify urges to pick, and then learn to tolerate the uncomfortable emotions that arise when they do not pick.

- Habit reversal training (HRT): Habit reversal training involves learning to be aware of the urge to pick, and then replacing picking behaviors with healthier behaviors.18

All three of these therapies can be effective in treating excoriation disorder, at least in the short term. However, results have been inconsistent in the long term.4,17

If you feel like you can’t stop picking at your skin, ask your doctor for a referral to a psychiatrist (can prescribe medications) or psychologist (can only provide counseling) who can help. Once you stop picking at your skin, you will be able to stay clear of acne much more easily, and you will dramatically reduce the chance that any acne that you do have will scar.

References

- Odlaug, B.L. & Grant, J.E. Pathologic skin picking. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 36, 296-303 (2010). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20575652

- Snorrason, I., Belleau, E.L. & Woods, D.W. How related are hair pulling disorder (trichotillomania) and skin picking disorder? A review of evidence for comorbidity, similarities and shared etiology. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 32, 618-29 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22917741

- Bethany L.Gelinas, M.G. Pharmacological and psychological treatments of pathological skin-picking: A preliminary meta-analysis. J. Obsessive Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2, 9 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK138035/

- Paylo, M.J., & Zins, A.A. Excoriation disorder: a new diagnosis in the DSM-5. American Counseling Association website: http://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/ethics/practice-briefs_june-2015.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2017.

- Lochner, C., Simeon, D., Niehaus, D.J. & Stein, D.J. Trichotillomania and skin-picking: a phenomenological comparison. Depress Anxiety 15, 83-6 (2002). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11891999

- Scheinfeld, N.S. Excoriation disorder. Medscape Updated Jan 26, 2016. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1122042-overview. Accessed: March 23, 2017.

- Schienle, A., Übel, S. & Wabnegger, A. Visual symptom provocation in skin picking disorder: an fMRI study. Brain Imaging Behav. 12, 1504-1512 (2018). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29305750

- Davey, G. C. Disgust: the disease-avoidance emotion and its dysfunctions. Philos. Trans R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 366, 3453-3465 (2011). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22042921

- Grant, J.E. et al. Skin picking disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 169, 1143-9 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23128921

- Bhate, K. & Williams, H.C. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br. J. Dermatol. 168, 474-85 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23210645

- Williams, H.C., Dellavalle, R.P. & Garner, S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet 379, 361-72 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21880356

- Grant, J. E. & Chamberlain, S. R. Prevalence of skin picking (excoriation) disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 130, 57-60 (2020). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32781374/

- Grant, J.E.P. & Potenza, M.N. The Oxford Handbook of Impulse Control Disorders (Oxford University Press, 2011). https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195389715.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780195389715

- Leibovici, V. et al. Excoriation (skin picking) disorder in Israeli University students: prevalence and associated mental health correlates. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 36, 686-9 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25150776

- Grant, J. E. & Chamberlain, S. R. Characteristics of 262 adults with skin picking disorder. Compr. Psychiatry 117, 152338 (2022). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35843137/

- Monzani, B. et al. Prevalence and heritability of skin picking in an adult community sample: a twin study. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 159B, 605-10 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22619132

- Stargell, N.A., et al. Excoriation disorder: assessment, diagnosis, and treatment. The Professional Counselor 6, 50-60 (2016). https://tpcjournal.nbcc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Pages_50-60-Stargell.pdf

- Torales, J., Díaz, N. R., Barrios, I., Navarro, R., García, O., O’Higgins, M., Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., Ventriglio, A. & Jafferany, M. Psychodermatology of skin picking (excoriation disorder): A comprehensive review. Dermatol. Ther. 33, e13661 (2020). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32447793/

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products