Research Is Ongoing, but an Anti-acne Vaccine Is Still a Long Way Away, If It Ever Arrives

The Essential Info

An acne vaccine would prevent acne from developing and help many people avoid years of acne treatment. In the past five decades, researchers have made major strides toward creating an acne vaccine. However, many technical obstacles remain, and an anti-acne injection at your doctor’s office is still years away from becoming reality, if in fact it ever does.

The Science

- What Exactly Is a Vaccine?

- Why Target C. acnes?

- How Would an Acne Vaccine Work?

- Why Isn’t an Acne Vaccine Available Yet?

Improving your acne can be a slow process, often involving trial and error until you find a treatment that works for you. To make matters worse, some of the commonly prescribed treatments, such as isotretinoin (Accutane®) and antibiotics, can also come with significant side effects.

Imagine the frustration and pain we could prevent if every child could go to his doctor for a routine checkup and, together with the vaccine against measles and mumps, get a quick injection to ward off acne.

Scientists are working on a few different approaches that show promise for an acne vaccine in the future. However, we are still years away from knowing whether a safe and effective vaccine will become a reality.

Let’s take a look at how an acne vaccine would work and what scientists still need to do to create one. But first, we need to understand exactly what a vaccine is.

What Exactly Is a Vaccine?

A vaccine is like a harmless version of an infection that we intentionally bring into the body to train our immune system to fight it. Once the immune system has learned to recognize and attack the harmless version, it will “remember” and be prepared when the harmful version comes along, rendering it inert before it creates disease.

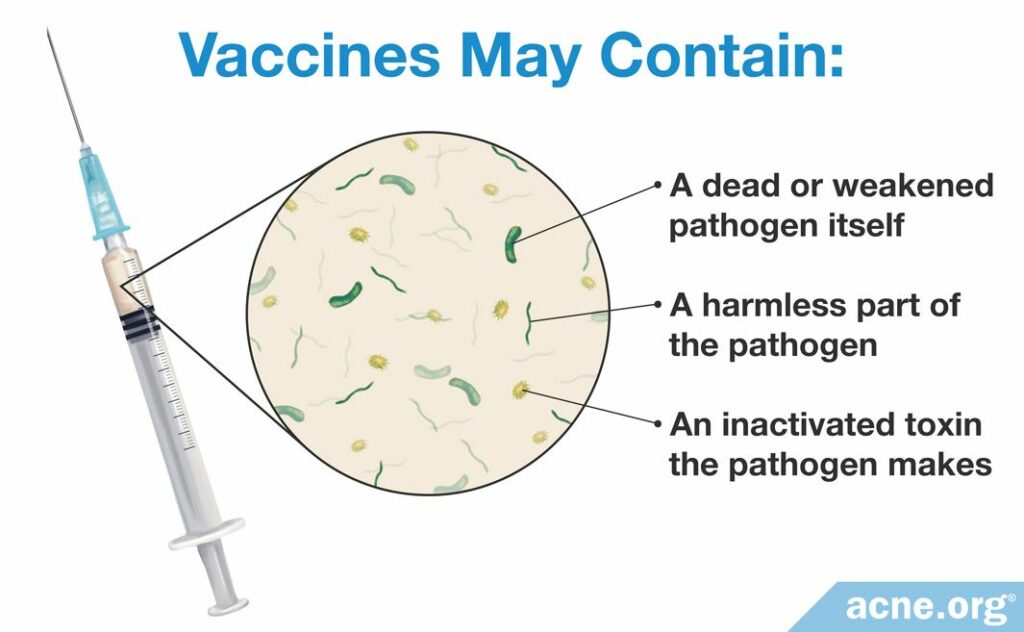

How exactly do we make a harmless version of an infection? Infections occur when a pathogen (usually some kind of bacteria or virus) enters the body and produces toxins or otherwise wreaks havoc. A vaccine usually consists of one of the following:

- A dead or weakened pathogen itself

- A harmless part of the pathogen

- An inactivated toxin the pathogen makes1-3

Vaccines have played an enormous role in preventing infectious diseases around the world. In fact, certain diseases, like polio, are almost completely eradicated thanks to vaccines.2

Now, you might be thinking, “But acne is not an infectious disease.” This is true, but a type of pathogen, in this case a type of bacteria called C. acnes, does contribute to acne. Let’s take a look at how targeting this type of bacteria might allow scientists to design a vaccine against acne.

Why Target C. acnes?

C. acnes is a type of bacteria that lives in the skin of almost all humans. It can contribute to acne by:

- Increasing skin oil production: C. acnes may stimulate the skin to produce too much skin oil, which is a key step in how acne begins.

- Stimulating skin cells to overgrow: C. acnes may speed up the production of new skin cells, and too many skin cells can clog pores.

- Increasing inflammation: C. acnes can intensify inflammation (redness, itching, and soreness) in skin pores, which is a critical part of how acne develops and worsens.4

In other words, C. acnes makes acne worse. Therefore, getting rid of C. acnes should improve acne. In fact, we know that treatments that kill C. acnes, like benzoyl peroxide and antibiotics, can improve acne.4

All of this gives scientists hope that a vaccine that trains the body to attack C. acnes could improve or perhaps even fully eliminate acne. However, the case is not so cut and dry. There are also good reasons why attacking C. acnes might not work, might only work somewhat, or might even be harmful to our health.

Targeting C. acnes might be a bad idea

Some scientists have doubts that attacking C. acnes would significantly reduce or eliminate acne, because acne can develop without this type of bacteria. Even inflammation, which is such a critical component of acne, can occur without C. acnes. Most likely, C. acnes only plays a role in the later stages of acne, increasing inflammation and making acne worse. In other words, getting rid of all C. acnes on a person’s skin might still allow acne to develop, but perhaps the acne would simply be milder without C. acnes.4

There is another good reason to approach a vaccine against C. acnes with caution. Almost everyone has C. acnes in their skin, and, under normal circumstances, this type of bacteria may be necessary for skin health.

According to a 2018 article published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, “Although C. acnes is suspected to be [disease-causing] in acne…[it] is also crucial for skin [health].”8 That is to say, it is possible that C. acnes is only harmful when it overgrows, whereas under normal circumstances, it is actually beneficial to skin health.

On balance, though, scientists still think designing a vaccine that targets C. acnes is worth a try. According to the authors of a 2013 article in the American Journal of Clinical Dermatology, “Despite many unanswered questions about C. acnes, [vaccination] with C. acnes holds promise for acne therapy.”4

How Would an Acne Vaccine Work?

As we have seen, an acne vaccine would have to contain one of the following:

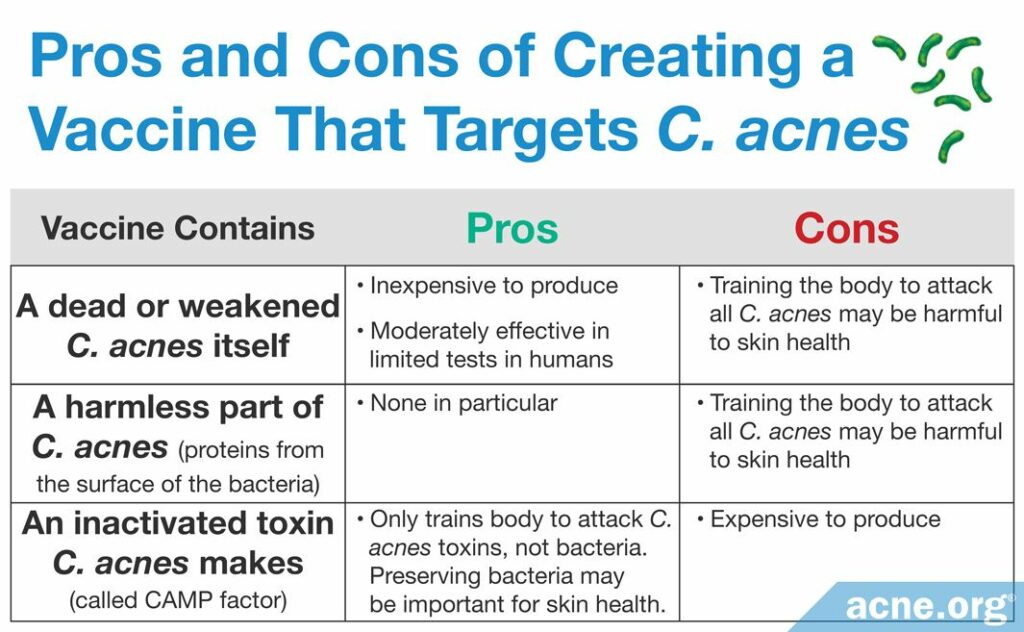

- A dead or weakened C. acnes itself: Scientists have recently tested a vaccine containing inactivated C. acnes on mice and found that it suppressed inflammation, which is a key component of acne.9

- A harmless part of C. acnes: Scientists have tried to develop a vaccine containing some proteins from the surface of C. acnes.4

- An inactivated toxin C. acnes makes: Today, scientists are working on a vaccine containing a toxin that C. acnes produces called CAMP factor (named after the initials of three scientists: Christie, Atkins, and Munch-Petersen). Currently, this approach shows the highest promise and is receiving the most attention from researchers. One reason why using an inactivated toxin is preferable to injecting dead bacteria or parts of bacteria is that this way is less likely to disrupt the so-called microbiome, which is the community of microorganisms that normally live in the body and contribute to its healthy functioning.4-6,10

Each of these vaccine types has some disadvantages.

The research on acne vaccines: The full scoop

Experiment 1: In 1979, scientists experimented with a vaccine containing a mix of killed C. acnes and another type of bacteria, P. granulosum. They tested this vaccine on people who already had severe acne. It is important to note that this is not the way doctors normally use a vaccine. Normally, a person receives a vaccine preemptively, before they actually come down with the disease itself, and the vaccine prevents them from ever getting sick from the disease. However, in this case, researchers gave the vaccine to people already suffering from acne and found that the vaccine improved acne in more than half of the participants.4

Experiment 2: In 2008, researchers tested another vaccine containing inactivated C. acnes, this time on mice. Mice don’t normally get acne, so the researchers first infected the mice with C. acnes, which caused inflammation of the mice’s ears. Next, the scientists gave the mice the vaccine. They found that the vaccine suppressed the growth of C. acnes and reduced inflammation in the skin of the mice.9 The researchers published their findings in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology in 2008.

To see whether an inactivated C. acnes vaccine might also reduce inflammation in humans, the same scientists went a step further. They took some human skin cells growing in a petri dish in the lab and infected them with C. acnes, which caused inflammation in the cells. The scientists then turned to the mice who had received the C. acnes vaccine, and removed some of the antibodies the mice’s bodies had produced in response to the vaccine. Antibodies are substances produced by the immune system to fight against a specific invader, in this case, C. acnes. The researchers then injected these antibodies into the human skin cells. As they had hoped, the antibodies produced by the mice thanks to the vaccine did reduce inflammation in the human skin cells. In a very roundabout way, this experiment yielded some evidence that an inactivated C. acnes vaccine might work in humans to fight the inflammation that occurs in acne.9

Despite these encouraging results, scientists were concerned that using a vaccine that trained the body to attack C. acnes might do more harm than good. Scientists speculate that only some specific types of C. acnes are harmful to humans, while others are actually beneficial to human skin health. They may be an important part of the so-called microbiome (a diverse set of bacteria that lives on and in the human body and helps protect us from disease).7 Therefore, in the decades that followed, researchers tried other approaches to creating an acne vaccine.

New approaches to an acne vaccine

More recently, scientists designed a vaccine using proteins from the surface of C. acnes called sialidases. Like the vaccine containing killed C. acnes, this vaccine trains the body to attack all C. acnes, even if the bacteria is not doing any harm. This again raises the concern that such a vaccine might actually damage skin health by killing useful bacteria.4,7

Now, scientists are working on a vaccine containing CAMP factor. This toxin triggers inflammation in the body. In other words, it may be that the bacteria is harmless in itself, and it is only the CAMP toxin it produces that worsens acne. Therefore, teaching the body to fight the toxin should decrease inflammation and help with acne.10

Experiment 3: To test this idea, researchers used mice that had C. acnes living in their skin. The scientists produced a vaccine containing CAMP factor and gave it to the mice. After receiving the vaccine, the mice exhibited decreased inflammation. Of course, since mice never develop acne, the researchers could not confirm that the vaccine also helped with acne. The scientists published the results of this study in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology in 2018.8 Although these results are promising, it is too early to tell whether the vaccine would work in people with acne.

Why Isn’t an Acne Vaccine Available Yet?

Despite promising research, we are still a long way off from an acne vaccine being available at your doctor’s office. Here are a few reasons why:

- There is no good animal model for acne. Normally, scientists test a vaccine on animals first before trying it in humans. However, since most animals do not suffer from acne, there is no reliable way to test whether a vaccine is likely to be safe and effective before trying it in humans.

- Testing a new vaccine and getting it approved for use in patients is a long process. To determine that a new vaccine is safe and effective, researchers have to conduct extensive testing in clinical trials (rigorous tests in a large number of patients). Regulators require such thorough, prolonged testing to ensure that the vaccine does not cause serious side effects. This process can take a decade or longer.

- Researchers need to find a cost-effective way to produce the vaccine. Theoretically, a person would receive the acne vaccine as a child to prevent developing acne at an older age. If the vaccine is too expensive, people may be reluctant to pay for it, especially since they do not know for sure whether they are even likely to develop acne. Therefore, researchers face the challenge not only of developing a safe and effective vaccine but also of ensuring that it is affordable.4,5

Other Promising Research Directions for Acne Treatment

Apart from trying to create a vaccine against acne, scientists are investigating other ways to combat the disease.

In a study published in 2018 in the journal Nature Communications, researchers looked at the DNA of a large number of people. They looked specifically at genes that control the shape of skin pores. The researchers found that certain variations in these genes result in skin pore shapes that are more prone to acne.11 In other words, the shape of your skin pores, which you may inherit from your parents, may make you more likely to develop acne. Now that scientists are beginning to learn which genes predispose people to acne, they can work on new genetic treatments to help prevent the disease.

Another promising strategy to combat acne is using topical probiotics. Probiotics are products containing beneficial bacteria that may help prevent the overgrowth of C. acnes on the skin. Normally, different species of bacteria living on the skin exist in a balance, and probiotics may help to restore that balance in acne-prone skin. However, probiotics that specifically target acne are still under investigation.12

The History of Vaccines

The first person to create a vaccine was an English doctor and scientist named Edward Jenner. He wanted to design a vaccine against smallpox, a disease that killed many people in the 18th century. Smallpox is caused by the smallpox virus. For his vaccine, Jenner used a similar, but weaker and less dangerous, virus called cowpox, which affects cows. People can also catch the virus from cows.

To produce the vaccine, Jenner took pus containing the cowpox virus from a sick milkmaid. In 1796, to test whether the vaccine protected people against smallpox, he injected the vaccine into an eight-year-old boy who was his gardener’s son. The boy came down with cowpox, which was an unpleasant but not dangerous infection. Then, Jenner exposed the boy to the lethal smallpox virus. By today’s standards, this was a highly unethical and dangerous experiment, but it worked. The boy was safe from smallpox. Jenner’s method became known as a “vaccine” after the Latin word for cow, vacca.2

References

- Ginglen, J. G. & Doyle, M. Q. Immunization. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459331/

- Vaccine, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vaccine

- Clem, A. S. Fundamentals of vaccine immunology. J Glob Infect Dis 3, 73 – 78 (2011). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3068582/

- Simonart, T. Immunotherapy for acne vulgaris: current status and future directions. Am J Clin Dermatol 14, 429 – 435 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24019180

- Liu, P. F., Nakatsuji, T., Zhu, W., Gallo, R. L. & Huang, C. M. Passive immunoprotection targeting a secreted CAMP factor of Propionibacterium acnes as a novel immunotherapeutic for acne vulgaris. Vaccine 29, 3230 – 3238 (2011). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21354482

- Kim, J. Acne vaccines: therapeutic option for the treatment of acne vulgaris? J Invest Dermatol 128, 2353 – 2354 (2008). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022202X15336411

- Contassot, E. Vaccinating against acne: Benefits and potential pitfalls. J Invest Dermatol 138, 2304 – 2306 (2018). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30170784

- Wang, Y. et al. The anti-inflammatory activities of Propionibacterium acnes CAMP factor-targeted acne vaccines. J Invest Dermatol 138, 2355 – 2364 (2018). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29964032

- Nakatsuji, T., Liu, Y. T, Huang, C. P., Zouboulis, C. C., Gallo, R. L & Huang, C. M. Antibodies elicited by inactivated Propionibacterium acnes-based vaccines exert protective immunity and attenuate the IL-8 production in human sebocytes: relevance to therapy for acne vulgaris. J Invest Dermatol 128, 2451-2457 (2008). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18463682/

- Keshari, S., Kumar, M., Balasubramaniam, A., Chang, T. W., Tong, Y. & Huang, C. M. Prospects of acne vaccines targeting secreted virulence factors of Cutibacterium acnes. Expert Rev Vaccines 18, 433-437 (2019). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30920859/

- Petridis, C. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis implicates mediators of hair follicle development and morphogenesis in risk for severe acne. Nat Commun 9, 5075 (2018). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-07459-5

- McLaughlin, J., Watterson, S., Layton, A. M., Bjourson, A. J., Barnard, E. & McDowell, A. Propionibacterium acnes and acne vulgaris: New insights from the integration of population genetic, multi-omic, biochemical and host-microbe studies. Microorganisms 7, 128. (2019). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31086023/

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products