Good Bacteria Keep Us Healthy, and Taking Antibiotics Kills Good Bacteria

The Essential Info

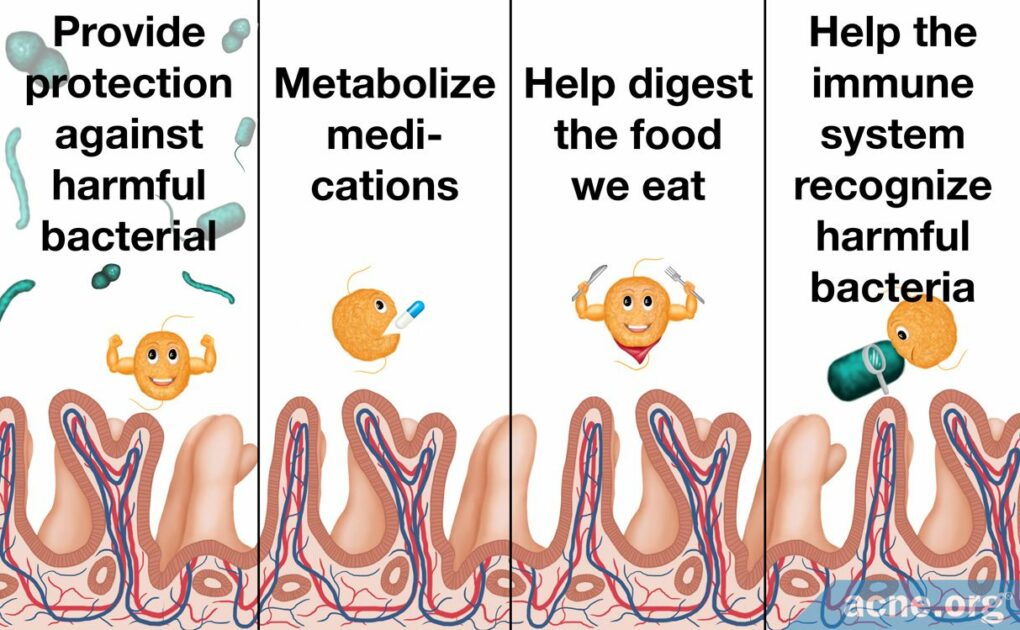

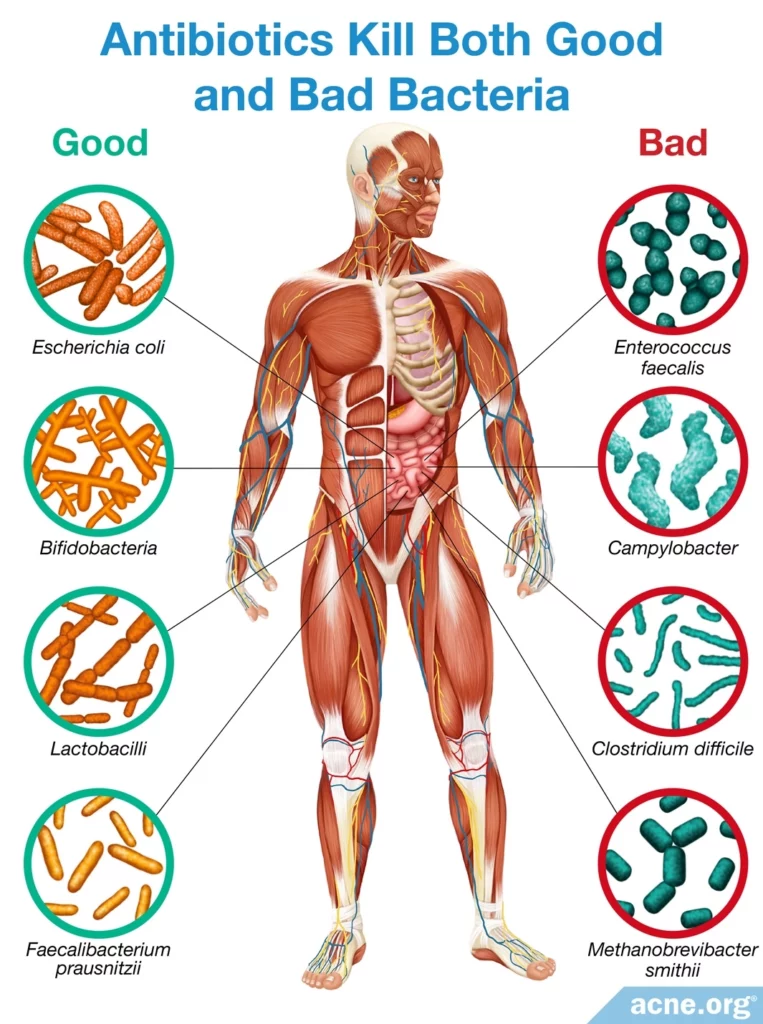

Trillions of bacteria live peacefully in our bodies and help to keep us healthy. Among other functions, these good bacteria help digest our food and help our immune systems recognize and fight off harmful bacteria.

Interestingly, recent evidence is showing us that in people with acne, the normal balance of gut bacteria may be disrupted. This might mean that it’s especially important for people with acne to avoid further disrupting the good bacteria present in their digestive systems.

The importance of a healthy gut microbiome should make all of us wary of taking antibiotics unless they are absolutely necessary. Despite their unimpressive effectiveness, oral antibiotics are sometimes prescribed for acne. When oral antibiotics disrupt the balance of bacteria in the body, side effects such as nausea and diarrhea can occur. In addition, when antibiotics kill good bacteria, this causes many other problems, including overgrowth of harmful bacteria that can cause disease, and antibiotic resistance.

Be Your Own Advocate: If your doctor prescribes an oral antibiotic for your acne, do not simply accept it. Be sure to ask about alternatives. And remember, your gut bacteria might be important in the fight against acne, so it’s safer to leave your gut alone whenever possible.

The Science

- Oral Antibiotics and Acne

- What Are Good Bacteria and What Is the Microbiome?

- Good Bacteria May Play a Role in Skin Health and Acne

- Treating Acne with Antibiotics Might Worsen Acne in the Long Term

- What Can Go Wrong When Antibiotics Kill Off the Good Bacteria?

- The Bottom Line

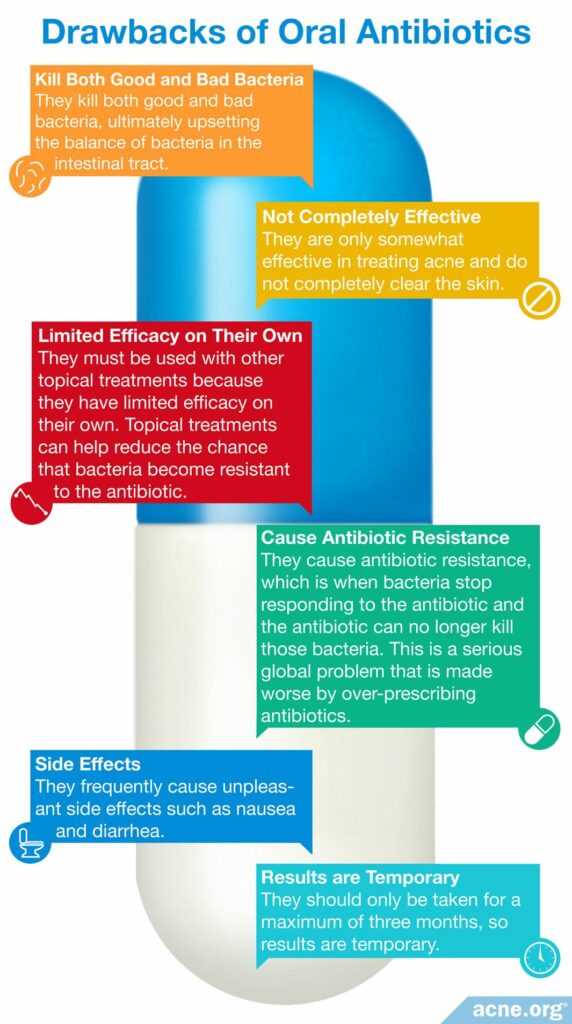

Despite declining popularity amongst both doctors and acne sufferers due to their incomplete efficacy, ability to provide only temporary relief, and worrying side effects, oral antibiotics remain a common acne treatment.

One of the ways antibiotics cause the most harm is through their ability to kill good bacteria and disrupt the balance of bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract. Since good bacteria perform important functions, the resulting imbalance causes health problems.

Oral Antibiotics and Acne

Doctors sometimes prescribe oral antibiotics for severe acne, truncal acne (acne on the chest and back), and moderate acne that does not respond to topical (applied to the skin) medications.

The most commonly prescribed oral antibiotics for acne are:

- Doxycycline

- Tetracycline

- Minocycline

- Erythromycin

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX)

- Amoxicillin

- Azithromycin1,2,5

Oral antibiotics can help improve acne by:

- Killing and preventing the growth of acne bacteria (C. acnes)

- Reducing inflammation1,2

Any oral antibiotic must be used alongside other topical treatments because they have limited efficacy on their own, and topical treatments can help reduce the chance that bacteria become resistant to the antibiotic.1-4

Common Side Effects of Oral Antibiotics for Acne

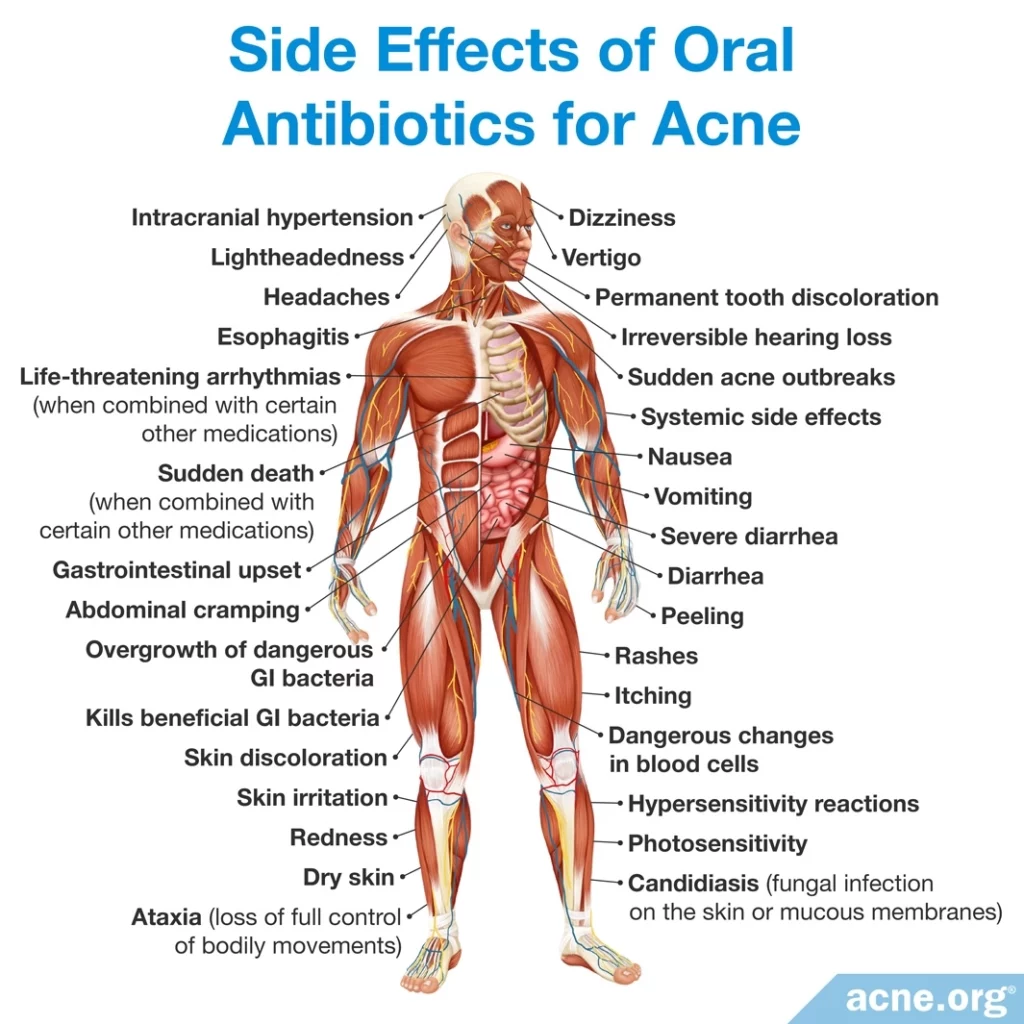

Because oral antibiotics kill not only bad bacteria but also good bacteria, they cause a variety of side effects, including gastrointestinal distress such as nausea and diarrhea. They can also reduce the ability of the body to absorb vitamins and medications, increase vulnerability to infections, and allow an overgrowth of harmful bacteria.

Expand to learn more about common side effects of oral antibiotics

Oral antibiotics are particularly well known for their ability to produce uncomfortable diarrhea:

According to a 2014 article in Annual Review of Microbiology, “Perhaps one of the most common side effects observed immediately after administration of antibiotics was antibiotic-associated diarrhea.”3

The most frequently prescribed oral antibiotics for acne, all of which kill good bacteria in the gut (intestines), are called tetracycline antibiotics (doxycycline, tetracycline, and minocycline). Their most common side effects are:

- Gastrointestinal distress, including diarrhea, in up to 50% of patients.

- Photosensitivity (increased sensitivity to sunlight) and other skin reactions such as itching or rashes, in up to 30% of patients.

- Permanent (lifelong) grey or blue color on the skin where an acne lesion was, or on the gums.

- Permanent (lifelong) yellow, grey, or brown tooth discoloration, in up to 3% of patients, mostly in children who are still growing.5

Tetracycline antibiotics are what are called “broad-spectrum antibiotics,” meaning they kill a wide array of bacteria, both good and bad. Let’s break this down and look at the major side effects of each of the tetracycline antibiotics:

- Doxycycline is the most prescribed oral antibiotic for acne in the United States. It causes gastrointestinal problems such as nausea and diarrhea in 20% to 30% of patients and photosensitivity in about 6% of patients.

- Tetracycline causes gastrointestinal problems in up to 50% of patients and skin reactions in up to 30% of patients. Tetracycline can also cause a vaginal fungal infection called vaginal candidiasis in some women.

- Minocycline causes the same side effects as the other two tetracyclines, but in addition it can cause severe side effects such as: dizziness, in up to 67% of patients; bluish-grey skin discoloration, in up to 3% of patients; and, rarely, drug-induced lupus (a chronic inflammatory disease).5

Some of these side effects are caused by properties of the antibiotics themselves. The gastrointestinal side effects, however, are a result of the way that oral antibiotics change the balance of bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract.

Most oral antibiotics do not only kill the particular bacteria that doctors are targeting; instead, they kill all bacteria in their path. This causes an imbalance in the types of bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract, and can lead to symptoms such as cramps, bloating, and diarrhea.4

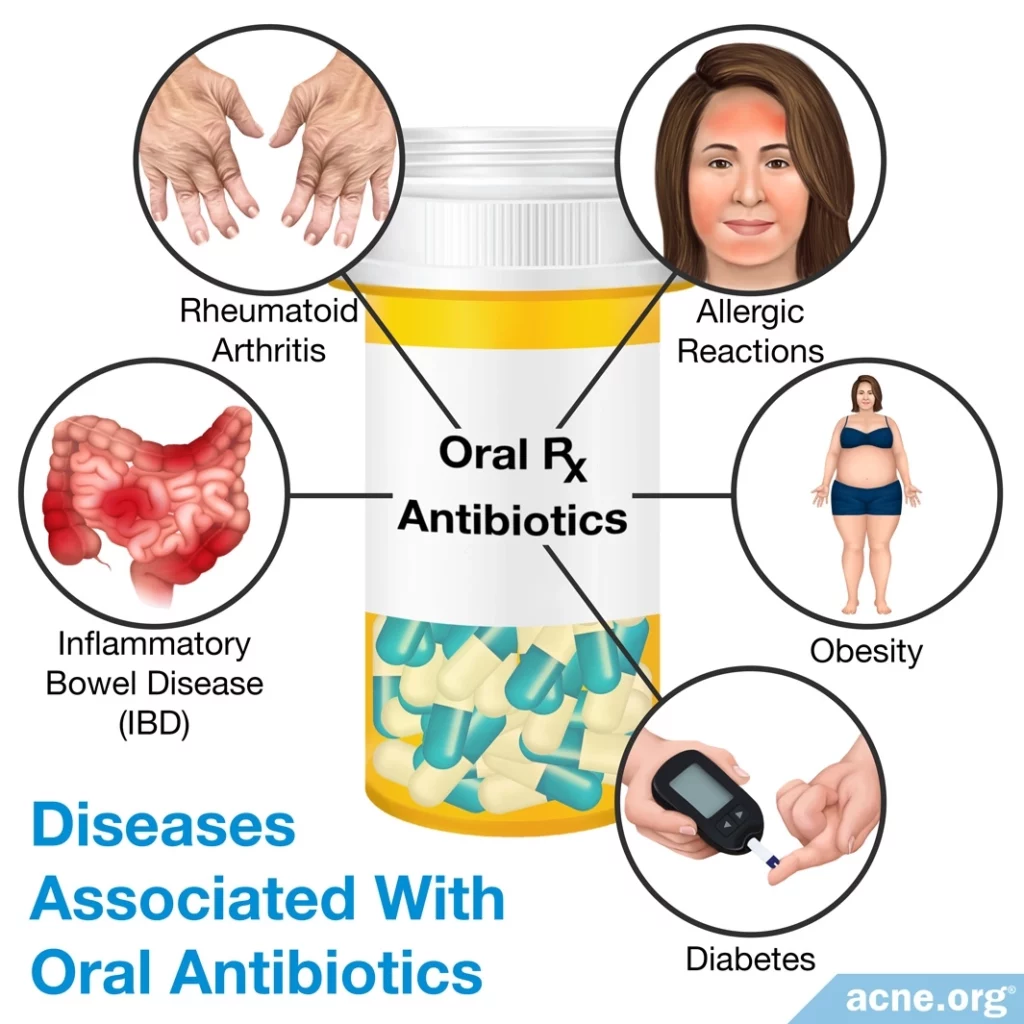

Diseases Associated With Oral Antibiotics

The imbalance of good bacteria caused by antibiotics can cause long-term health problems. In fact, research has shown an association between such an imbalance and chronic diseases that involve the immune system, such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, allergic reactions, and obesity. Harmful bacteria in the gut can influence these diseases because the bacteria interact with immune cells and can make the immune system overreact to things that it would not normally react to. These reactions can then spread through the bloodstream throughout the body and cause disease.3

A 2014 article in Annual Review of Microbiology underlines the point that good bacteria are needed to prevent disease:

“A common feature of diseases linked to microbial [imbalance] is a significant reduction in bacterial diversity.”3

What Are Good Bacteria and What Is the Microbiome?

We take antibiotics to kill bacteria that are harmful. However, not all bacteria are harmful. In fact, many trillions of bacteria live in and on our bodies and play an important role in keeping us healthy. Scientists estimate that the human body has 10 times more cells from bacteria than human cells. Most of these species live in the gastrointestinal tract, especially in the colon.3,5

According to a 2010 article in Microbiology, “Practically all surfaces of the human body exposed to the environment are normally inhabited by [microbes]. The intestine constitutes an especially rich and diverse microbial habitat. Approximately 800-1000 different bacterial species and >7000 different strains inhabit the gastrointestinal tract.”4

Bacteria living in the human body interact with each other and with our cells. Good bacteria provide protection against harmful bacterial species, help the immune system recognize which bacteria are harmful, and provide many other functions that keep us healthy. Scientists call the relationship between good bacteria and humans symbiotic, meaning that the relationship benefits both bacteria and humans.3,4,6

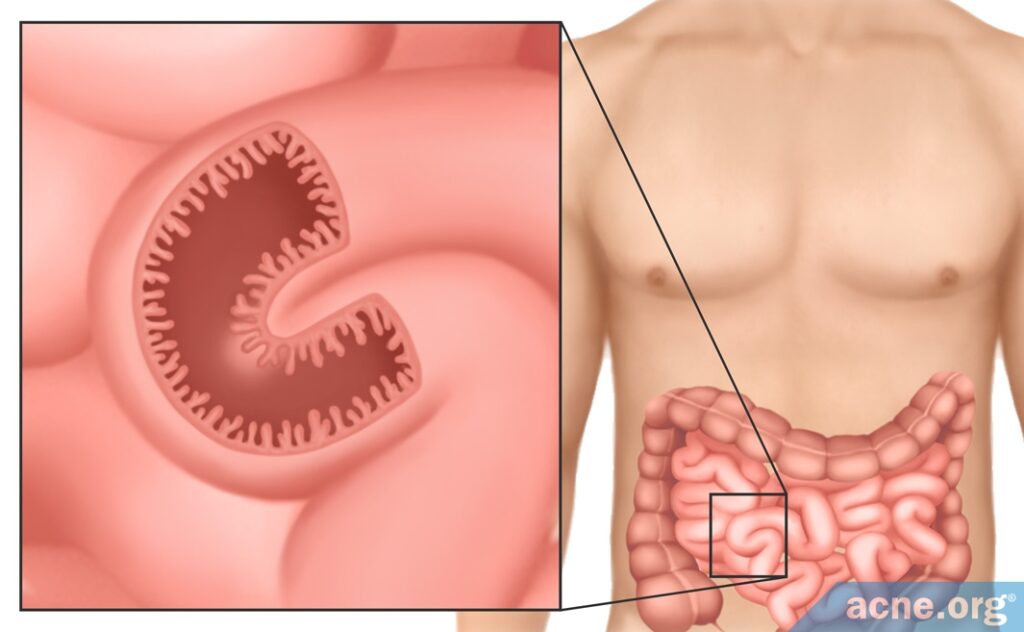

Bacteria that live in the gut in particular help digest food, produce vitamins, and maintain healthy intestines. In addition, gut bacteria in a developing fetus are necessary for it to develop a normal, healthy gastrointestinal tract. Gut bacteria help the developing intestines to form the blood supply, immune system, and intestinal barrier. The intestinal barrier is a protective layer of cells that allows the intestinal wall to absorb nutrients from food while at the same time keeping harmful bacteria out. Because the gut is always processing the food we eat, the protective layer of cells needs to be renewed constantly in order to keep the barrier intact. Normally, the barrier can be completely renewed within a week, but without good bacteria, it takes twice as long. In another example of how important these bacteria are, studies have shown that the intestines develop abnormally in mice that have no bacteria in their guts. As we can see, good bacteria are essential to healthy gut function.4,7

Scientists refer to the collection of microbes that lives in us as the microbiota, and to the entire ecosystem of the microbiota, which includes the microbes, their genes, and the environment in which they live, as the microbiome. The study of the microbiome is an area of ongoing research, and there is still much that we don’t know about it. For example, scientists don’t know exactly which species or combinations of species are necessary for a healthy microbiome.3,6

Good Bacteria May Play a Role in Skin Health and Acne

Surprisingly, good bacteria living in the gut may also play an important role in the health of the skin. Over the past century, scientists have been developing a theory about the so-called gut-brain-skin axis. The idea is that these three parts of the body are linked, and an imbalance in the bacteria living in the gut can have negative effects on skin health.8

Studies show that people with acne have fewer different types of gut bacteria compared to people without acne. In addition, people with acne may have higher concentrations of some specific types of gut bacteria as well.9 So, scientists speculate that having less variety of good bacteria in the gut can make a person more vulnerable to developing acne.10,11

Expand to read details of studies

A study published in the journal Acta Dermato-Venereologica in 2018 looked at the gut microbes of 43 people with acne and 43 people without acne. To see what types of bacteria were living in the intestines, the researchers collected feces from all the participants. The scientists found a significant difference in the balance of gut bacteria in people with acne compared to people without acne. People with acne were lacking in several species of beneficial gut bacteria, such as Clostridia, Clostridiales, Lachnospiraceae, and Ruminococcaceae.9

Similarly, another study published in The Journal of Dermatology in 2018 also looked at the difference in gut microbes between people with and without acne. In this study, researchers collected fecal samples from 31 people with moderate-to-severe acne and 31 people without acne. After analyzing the samples, the scientists found that, compared to people without acne, people with acne were lacking in beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium, Butyricicoccus, Coprobacillus, Lactobacillus, and Allobaculum. These types of bacteria help to maintain a healthy internal environment in the intestine and aid the gut in recovering from severe inflammatory reactions.11

As for the role that the brain plays in this theory, researchers speculate that psychological stress may change the activity of gut bacteria, causing them to trigger inflammation, which can worsen acne. Scientists wonder whether this might explain why stress sometimes goes hand-in-hand with acne flare-ups.10

According to a 2019 article in the Journal of Clinical Medicine, “Until recently, diet and psychological stress were thought to have little relevance to the [development] of acne. However, with the understanding that the brain-gut-skin axis exists, it is now clear that intestinal microbes have significant effects on acne.”10

Treating Acne with Antibiotics Might Worsen Acne in the Long Term

Considering that an imbalance in gut bacteria may contribute to acne, treating acne with antibiotics may come with pros and cons:

- Pro: On the one hand, antibiotics may provide short-term improvement by killing bad bacteria on the skin.

- Con: On the other hand, antibiotics may cause more skin problems in the long run by disrupting the balance of good bacteria in the gut.

What Can Go Wrong When Antibiotics Kill Off the Good Bacteria?

Because oral antibiotics kill bacteria indiscriminately, they change the balance of bacteria in the gut, which can lead to problems, including the many side effects associated with antibiotics, particularly gastrointestinal upset.

The impact of antibiotics on the microbiome depends on the antibiotic used. The factors that affect how harmful an antibiotic is to the microbiome include:

- The variety of species that it kills: Many oral antibiotics, including the tetracyclines, are broad-spectrum antibiotics, meaning that they kill a wide variety of bacterial species.

- The dose and duration of treatment: Taking antibiotics in higher doses or for a longer period of time makes it more likely that they will harm the microbiome. Antibiotics for acne are normally taken for 3 months or more, which is a very long time.

- The way the body processes the antibiotic: Antibiotics that take longer to be absorbed stay inside the intestines and will kill more bacteria inside the intestines.4,7

The Loss of Colonization Resistance

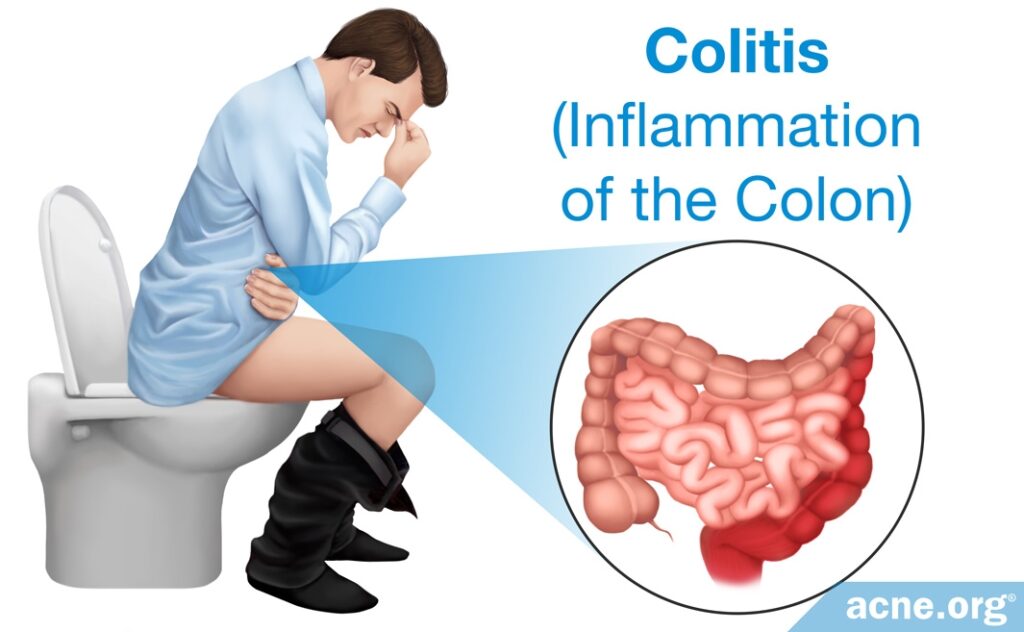

Since the 1950s, evidence has been accumulating that when antibiotics kill good bacteria and change the balance of the microbiome, this can lead to infections by something called “opportunistic pathogens.” Opportunistic pathogens are microbes that normally live in the body without causing problems but that take advantage of an imbalance in the microbiome to cause infection. Antibiotics give opportunistic pathogens an opportunity to cause harm. Normally, good bacteria prevent the growth of harmful bacteria. This prevention strategy is called colonization resistance, meaning that the good bacteria prevent harmful bacteria from taking up residency in the gut. When antibiotics kill good bacteria, harmful bacteria can grow and cause disease. For example, antibiotics such as oral clindamycin can lead to overgrowth of C. difficile, a strain of bacteria that is responsible for gastrointestinal problems such as diarrhea and colitis (inflammation of the colon). C. difficile can cause severe, life-threatening diarrhea.3,12

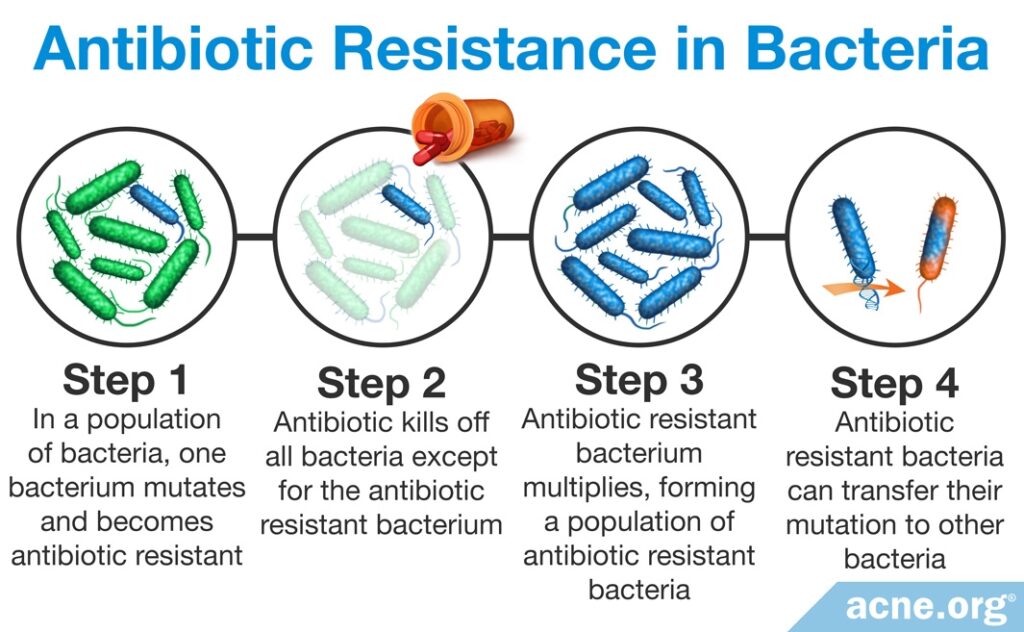

Spread of Resistant Bacteria

When you take an antibiotic, some harmful bacteria become resistant to the antibiotic and survive. Since most antibiotics kill many good bacteria, resistant harmful bacteria have an opportunity to grow and multiply. When you stop taking the antibiotic, the good bacteria can no longer contain the resistant harmful bacteria, and the resistant bacteria settle in the gut and can live there for many years. If these bacteria later cause infection, it will be impossible to kill them with the same antibiotic because they are now resistant to the antibiotic. Often, these bacteria become resistant to multiple antibiotics. Antibiotic resistance is a very serious threat to human health because there will come a time when many different bacteria are resistant to all antibiotics and we will not be able to treat bacterial infections. When this happens, routine infections such as strep throat that we now treat with antibiotics will be untreatable and may lead to death.4

The Bottom Line

Oral antibiotics can literally be lifesavers when they are absolutely required to cure a disease. However, particularly when taken for long periods of time, like they often are in acne patients, they can become harmful. If your doctor prescribes antibiotics for your acne, ask her if there are other options that could help that are as effective with less side effects.

References

- Costa, C. S. & Bagatin, E. Evidence on acne therapy. Sao Paulo Med. J. 18, 193 – 197 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23903269

- Oudenhoven, M. D., Kinney, M. A., McShane, D. B., Burkhart, C. N. & Morrell, D. S. Adverse effects of acne medications: recognition and management. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 16, 231 – 242 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25896771

- Keeney, K. M., Yurist-Doutsch, S., Arrieta, M.-C. & Finlay, B. B. Effects of antibiotics on human microbiota and subsequent disease. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 68, 217 – 235 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24995874

- Jernberg, C., Löfmark, S., Edlund, C. & Jansson, J. K. Long-term impacts of antibiotic exposure on the human intestinal microbiota. Microbiology 156, 3216 – 3223 (2010). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20705661

- Tripathi, S. V, Gustafson, C. J., Huang, K. E. & Feldman, S. R. Side effects of common acne treatments. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 12, 39 – 51 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23163336

- Findley, K. & Grice, E. A. The skin microbiome: a focus on pathogens and their association with skin disease. PLoS Pathog. 10, 10 – 12 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4231143/

- Moens, E. & Veldhoen, M. Epithelial barrier biology: Good fences make good neighbours. Immunology 135, 1 – 8 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22044254

- Mahmud, M. R., Akter, S., Tamanna, S. K., et al. Impact of gut microbiome on skin health: gut-skin axis observed through the lenses of therapeutics and skin diseases. Gut Microbes 14, 2096995 (2022). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35866234/

- Deng, Y., Wang, H., Zhou, J., Mou, Y., Wang, G. & Xiong, X. Patients with acne vulgaris have a distinct gut microbiota in comparison with healthy controls. Acta Derm. Venereol. 98, 783-790 (2018). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29756631/

- Lee, Y. B., Byun, E. J. & Kim, H. S. Potential role of the microbiome in acne: A comprehensive review. J. Clin. Med. 8, 987 (2019). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6678709/

- Yan, H. M., Zhao, H. J., Guo, D. Y., Zhu, P. Q., Zhang, C. L. & Jiang, W. Gut microbiota alterations in moderate to severe acne vulgaris patients. J. Dermatol. 45, 1166-1171 (2018). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30101990/

- Bäumler, A. J. & Sperandio, V. Interactions between the microbiota and pathogenic bacteria in the gut. Nature 535, 85 – 93 (2016). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27383983

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products