Facial Skin Is More Delicate and Requires Special Care

The Essential Info

Skin on the Face: Skin pores on the face are smaller than on the rest of the body and contain a higher concentration of skin oil glands. Skin oil is essential for the development of acne, and this is why we see acne affect the face so often. Skin on the face is also thinner and more delicate than it is on the body, and therefore needs a gentler treatment regimen.

Skin on the Body: Skin pores and skin oil glands on the body are larger than they are on the face. This is why when acne lesions occur on the body, the lesions tend to be larger in size. Skin on the body is thicker and hardier than it is on the face, and can therefore handle a more aggressive treatment regimen.

The Science

- Epidermis

- Comparing the Epidermis of the Face to That of the Body

- Comparing the Dermis of the Face to That of the Body

- Hypodermis

- Treat Your Facial Skin More Gently

The skin on the face and body differ in these key areas:

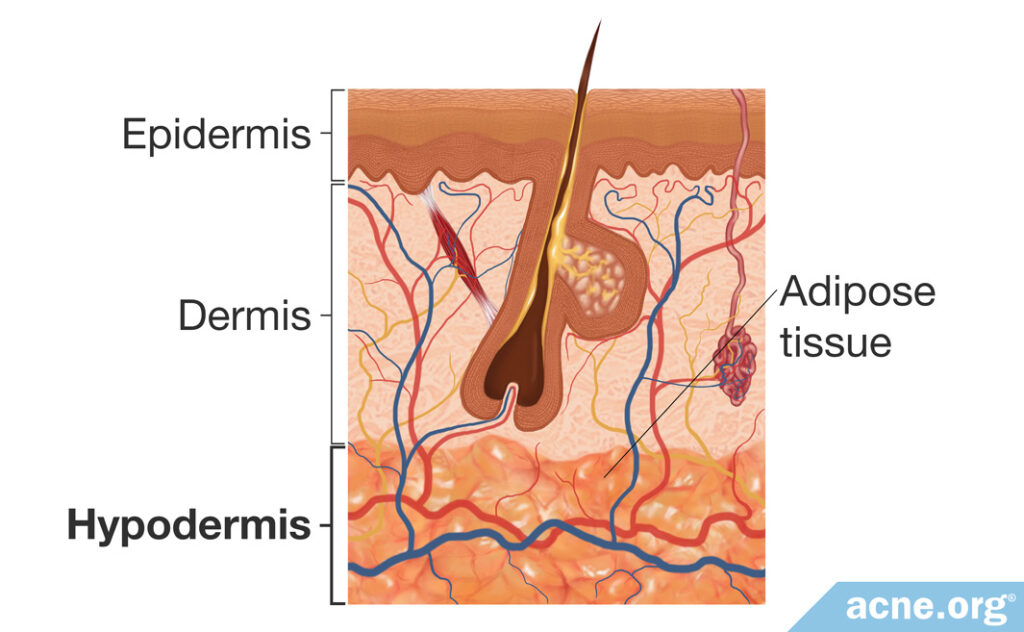

- Anatomy: Skin consists of three layers and differences between facial skin and bodily skin are present in each of these layers:

1. Epidermis (top)

2. Dermis (middle)

3. Hypodermis (bottom) - Skin care / Acne care: Caring for the skin on your face requires a gentler regimen while skin on the body can normally handle a more aggressive regimen.

Let’s have a look at how the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis differ between the face and body, and why the skin on the face needs to be treated more gently.

Caution – lots of deep science ahead: I’m going to get pretty deep into anatomy. If you enjoy learning that kind of thing, read on. If not, just know that the skin of the face is thinner and more sensitive than the body and must be treated more gently.

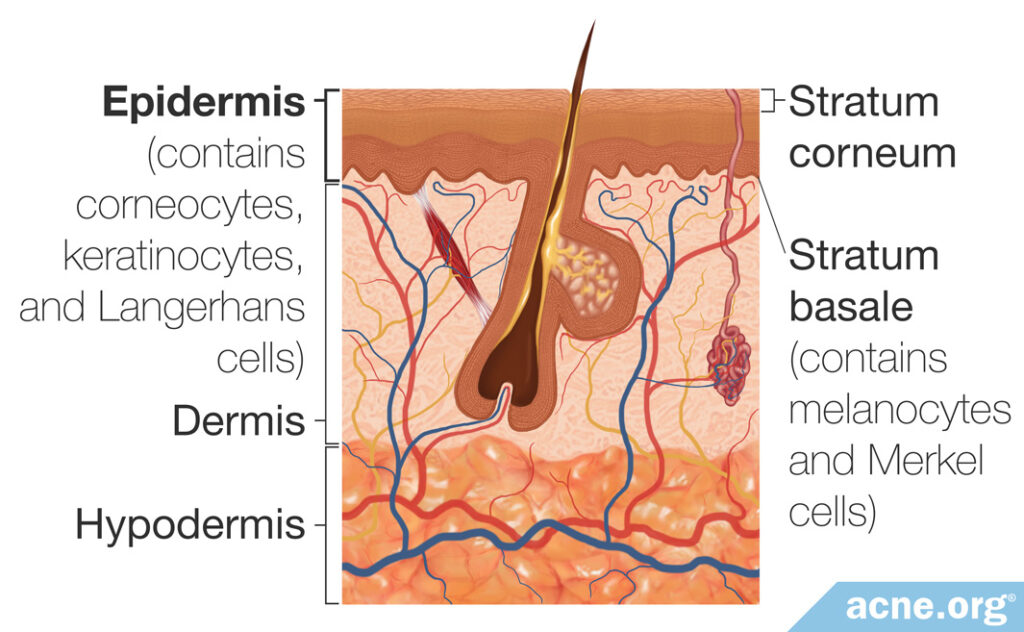

Epidermis

The epidermis is the outer layer of the skin, responsible for preventing entry of foreign substances into the skin as well as preventing water loss from the skin.

It is further divided into several sublayers, which include the stratum basale and the stratum corneum. These sublayers are composed of different types of cells.1

The stratum basale is the innermost layer of the epidermis. Different cells in the stratum basale contribute to the skin’s color, sense of touch, and protective effects:

- Keratinocytes make up 90% of epidermal cells. In the stratum basale, they undergo repeated cell division to form new cells that continuously replace older cells. As old keratinocytes are replaced, they move through the upper layers of the epidermis toward the skin’s surface, where they undergo structural and chemical changes that transform them into cells called corneocytes.

- Melanocytes are cells that produce a pigment called melanin, which gives rise to skin and hair color. Melanin also provides protection from harmful ultraviolet rays present in sunlight.

- Langerhans cells form part of the skin’s immune system. These cells help detect foreign substances and defend the body from infection. However, they also are responsible for the development of skin allergies.

- Merkel cells, also called tactile cells, are modified nerve endings that are responsible for the detection of touch.2,3

The stratum corneum is the outermost layer of the epidermis. It is relatively waterproof and, when undamaged, prevents most bacteria, viruses, and other foreign substances from entering the body.

Corneocytes are the main component of the stratum corneum. These cells acquire structures called desmosomes on their surface so that they adhere to one another. A lipid (fat) layer envelopes the corneocytes, helping to prevent water loss. They also contain proteins and molecules that make up part of the natural moisturizing factor (NMF), which is made up of molecules that bind water and hydrate the skin. As they mature, corneocytes become tougher, creating the skin’s protective outer layer.4

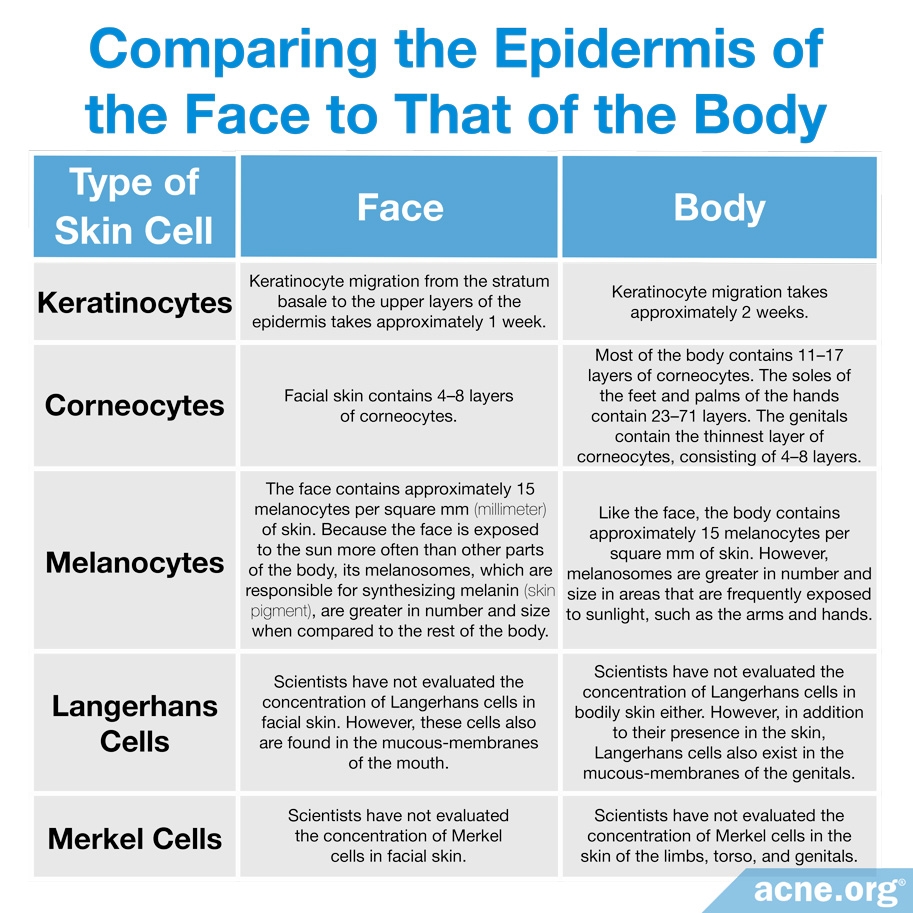

Comparing the Epidermis of the Face to That of the Body

The distribution of different types of cells varies throughout the body. In general, the epidermis of the face is thinner than the epidermis of the rest of the body, except on the genitals. In facial skin, corneocytes are smaller in size yet higher in number when compared to those on the rest of the body. The table below describes how the cells of the epidermis on the face are different from those on other parts of the body.

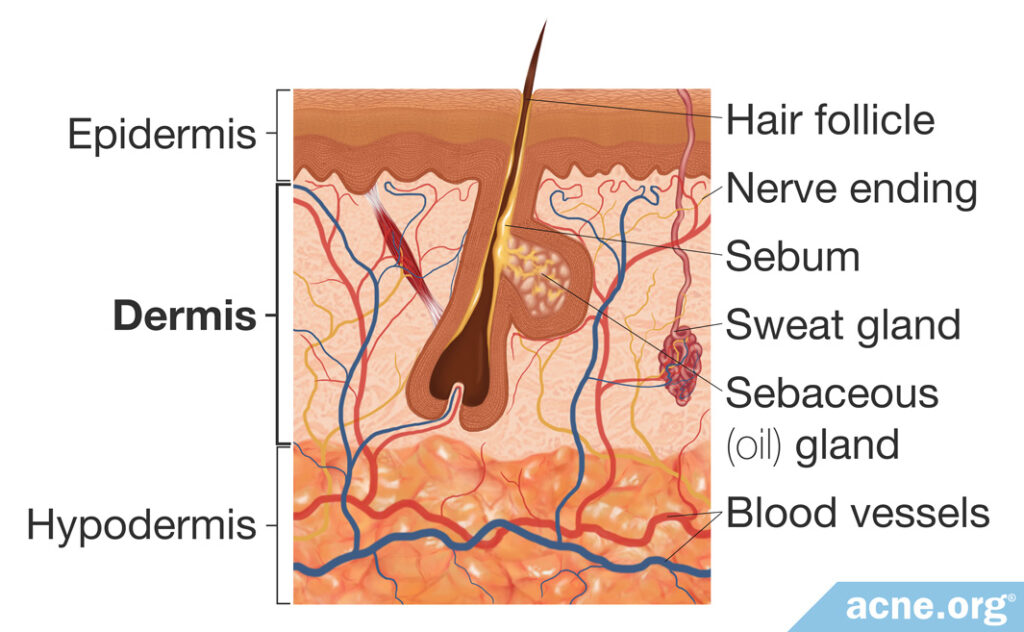

Dermis

The dermis lies below the epidermis. The fibrous and elastic tissue of the dermis is responsible for the skin’s strength and elasticity. It also contains blood vessels, sweat glands, sebaceous (oil) glands, hair follicles, and nerve endings.

- Blood vessels of the dermis provide nutrients to the dermis and epidermis. Because the epidermis does not contain blood vessels, it depends on the blood vessels of the dermis to provide nourishment. The blood vessels of the dermis are important also in temperature regulation, which is a vital function of the skin. High temperatures cause enlargement of blood vessels so that more blood flows near the skin’s surface, where heat is released. Conversely, cold temperatures cause the blood vessels to constrict. This reduces blood flow to the surface of the skin in order to conserve heat.7,8

- Sebaceous glands usually are attached to hair follicles. They secrete an oily substance called sebum, which lubricates and waterproofs the skin. Sebaceous glands also provide antibacterial protection.9

- Sweat glands are divided into two types: (1) apocrine glands and (2) eccrine glands. Apocrine glands develop in areas that contain an abundance of hair, such as the armpits and groin. There they secrete a milky fluid that develops an odor when it interacts with bacteria on the body. Eccrine glands are not associated with hair follicles. They produce clear sweat, which helps control body temperature as it evaporates off the skin.10

- Hair follicles are responsible for producing hair which, on the skin, helps regulate body temperature as well as enhances sensation. There are two types of bodily hair: (1) vellus hair and (2) terminal hair. Vellus hairs are soft, fine, and lightly pigmented. Vellus hair is common in infants and children but largely are replaced by terminal hair in adults. Terminal hair is longer, coarser, and darker than vellus hair. During puberty, terminal hair grows on the genital area and armpits of both males and females, and also on the face, chest, arms, and feet of men.1

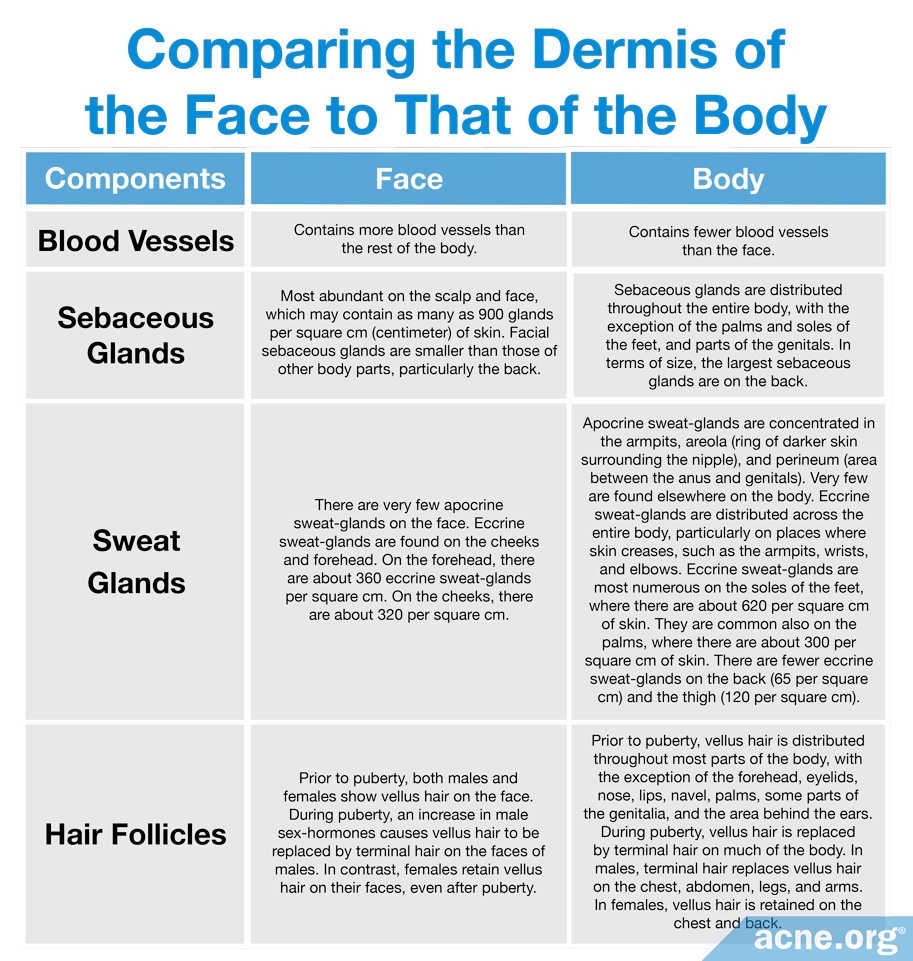

Comparing the Dermis of the Face to That of the Body

The components of the dermis vary depending on location. For example, the face contains more blood vessels and sebaceous glands than other parts of the body,8 but it contains very few apocrine sweat glands. The table below describes how the components of the dermis are distributed on the face in contrast to other parts of the body.

Hypodermis

The hypodermis is the innermost layer of the skin. It contains a layer of fat cells that insulate the body, protecting it from heat and cold.11 The fatty tissue of the hypodermis is called adipose tissue. Adipose tissue also provides a protective padding and stores energy for the body to use during times of caloric deficiency.12

Comparing the Hypodermis of the Face to That of the Body

Genetic factors affect the distribution of adipose tissue. Environmental factors such as diet and exercise determine its thickness. In general, the hypodermis is thickest in the thighs, hips, and buttocks in females. In males, it is thickest in the abdomen and thighs. In both sexes, the hypodermis of the face is thickest in the cheeks. Evidence suggests that the number of adipocytes (fat-storage cells) remains constant after puberty in lean individuals. However, when people consume excess calories, adipocytes can increase in volume, and new adipocytes can be generated. Short-term overeating increases the size of adipocytes in lean individuals. In obese individuals, overeating also increases the size but appears to increase the number of adipocytes as well.12,13

Treat Your Facial Skin More Gently

Because the skin of the face is thinner and more delicate when compared to skin on the body, it needs a gentler treatment regimen. In contrast, the skin on the body is thicker and tougher, and can normally handle a more aggressive treatment regimen.

The face is also exposed to wind and harsh weather conditions and is more likely to dry out compared to other parts of the body, which are usually covered.14 This means moisturizing may be particularly important for the skin of the face in the colder months of the year.

References

- Amirlak, B. Skin Anatomy. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1294744-overview#a2

- Eckert, R. L. & Rorke, E. A. Molecular biology of keratinocyte differentiation. Environ. Health Perspect. 80, 109 – 116 (1989). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2466639

- Thingnes, J., Lavelle, T. J., Hovig, E. & Omholt, S. W. Understanding the melanocyte distribution in human epidermis: An agent-based computational model approach. PLoS ONE 7, e40377 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22792296

- Van Logtestijn, M. D. A., Dominguez-Hittinger, E., Stamatas, G. N. & Tanaka, R. J. Resistance to water diffusion in the stratum corneum is depth-dependent. PLoS ONE, e0117292 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25671323

- Tagami, H. Location-related differences in structure and function of the stratum corneum with special emphasis on those of the facial skin. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 30, 413 – 434 (2008). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19099543

- Mohammed, D., Matts, P. J., Hadgraft, J. & Lane, M. E. Variation of stratum corneum biophysical and molecular properties with anatomic site. AAPS J. 14, 806 – 812 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3475846/

- Sandby-Møller, J., Poulsen, T. & Wulf, H. C. Epidermal thickness at different body sites: relationship to age, gender, pigmentation, blood content, skin type and smoking habits. Acta Derm. Venereol. 83, 410 – 413 (2003). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14690333

- Khavkin, J., Ellis, D. A. Aging skin: histology, physiology, and pathology. Facial Plast. Surg. Clin. North Am. 19, 229-234 (2011). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21763983/

- Ebling, F. The Sebaceous Glands 16, 495 – 411 (1965).

- Taylor, N. A. & Machado-Moreira, C. A. Regional variations in transepidermal water loss, eccrine sweat gland density, sweat secretion rates and electrolyte composition in resting and exercising humans. Extrem. Physiol. Med. 2, 4 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3710196/

- Arens, E. A. & Zhang, H. The skin’s role in human thermoregulation and comfort. Thermal and Moisture Transport in Fibrous Materials, eds N. Pan and P. Gibson, Woodhead Publishing Ltd, pp 560-602 (2006). https://viterbik12.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/2006-Thermal-and-Moisture-Transport-in-Fibrous-Materials-Arens2c-Zhang-The-skin’s-role-in-human-thermoregulation-and-comfort2.pdf

- Svensson, H. Human adipose tissue morphology and function: relation to insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance with focus on pregnancy and women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus. (Institute of Biomedicine. Department of Clinical Chemistry and Transfusion Medicine, Gothenburg, 2015). https://gupea.ub.gu.se/handle/2077/39574

- Kruglikov, I., Trujillo, O., Kristen, Q., Isac, K., Zorko, J., Fam, M., Okonkwo, K., Mian, A., Thanh, H., Koban, K., Sclafani, A. P., Steinke, H. & Cotofana, S. The facial adipose tissue: A revision. Facial Plast. Surg. 32, 671-682 (2016). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28033645/

- Machado, M., Hadgraft, J. & Lane, M. E. Assessment of the variation of skin barrier function with anatomic site, age, gender and ethnicity. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 32, 397‐409 (2010). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20572883

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products