Acne Is a Complex Disease That Forms Through a Series of Complicated Biological Processes

The Essential Info

In this article, we’ll take a deep dive into theories of acne development. For a simpler, easy-to-understand article, visit the What Is Acne page.

Normally I’ll summarize the article up here in The Essential Information area, but there’s too much detail when it comes to theories on acne development to tie it up in a bow like that, so I recommend just getting nerdy and reading the full article below.

If I was forced to summarize it quickly, basically it comes down to inflammation and exactly where inflammatory molecules get involved in acne development. In the past, acne researchers thought inflammation came late in an acne lesion’s development, but the more research that comes in, the more it looks like inflammation is actually there from the very start of an initial clogged pore. In other words, acne really may be at its very core a chronic inflammatory disease.

The Science

- The Sebaceous Follicle

- What Causes a Clogged Pore

- Early Stages in Clogged Pore Development

- How Inflammation Is Involved in the Early Stages of Acne

- Formation of Non-inflammatory Acne Lesions: Microcomedones and Comedones

- Formation of Inflammatory Acne Lesions: Papules and Pustules

- Severe Acne

This article will take a deep dive into how acne is formed. If you prefer a simpler explanation, see our What Is Acne page.

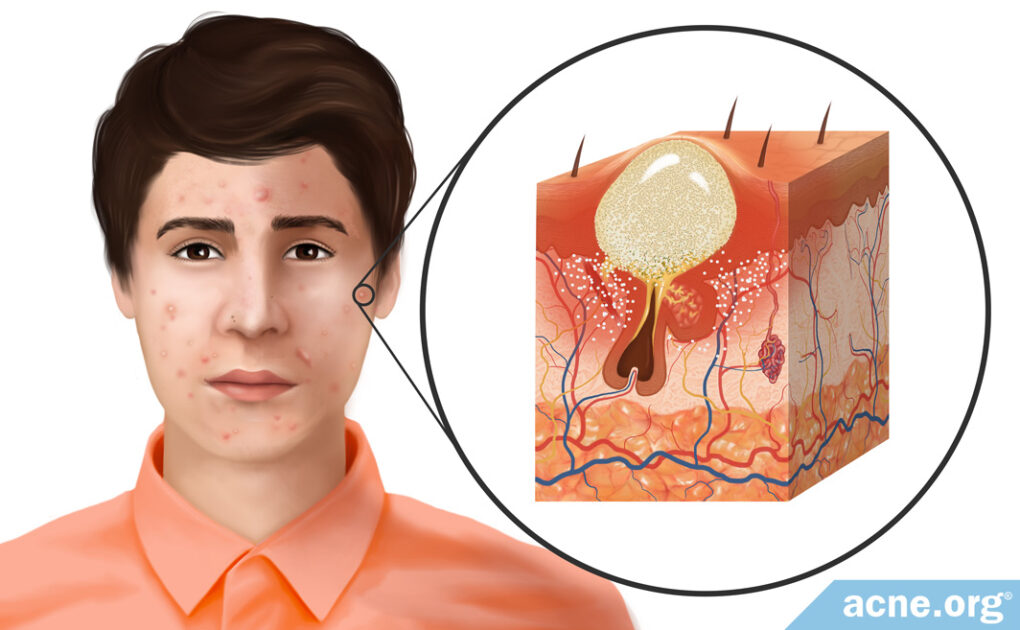

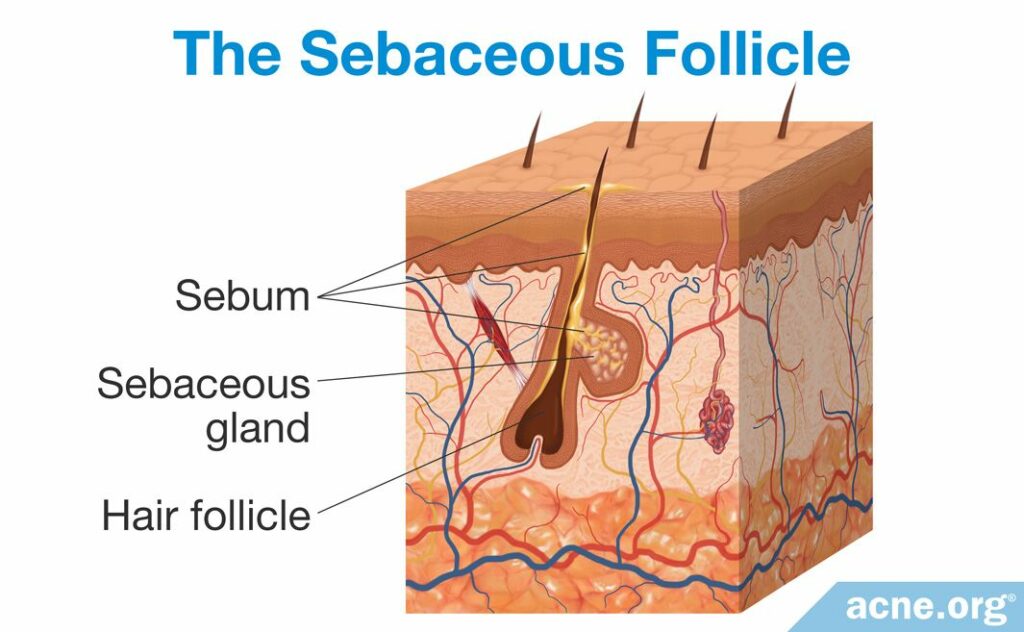

The Sebaceous Follicle

Acne formation begins in the pores of the skin, called sebaceous follicles. These follicles contain two main components: sebaceous glands and vellus hair. Sebaceous glands produce sebum (skin oil), and vellus hair is the thin, short hair that is nearly invisible to the eye. Sebaceous follicles are abundant all over the body except on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. On the face, they are especially numerous, with 200+ follicles covering each square centimeter.

What Causes a Clogged Pore

An acne lesion forms when a sebaceous follicle becomes clogged. There is a variety of factors that can cause this.

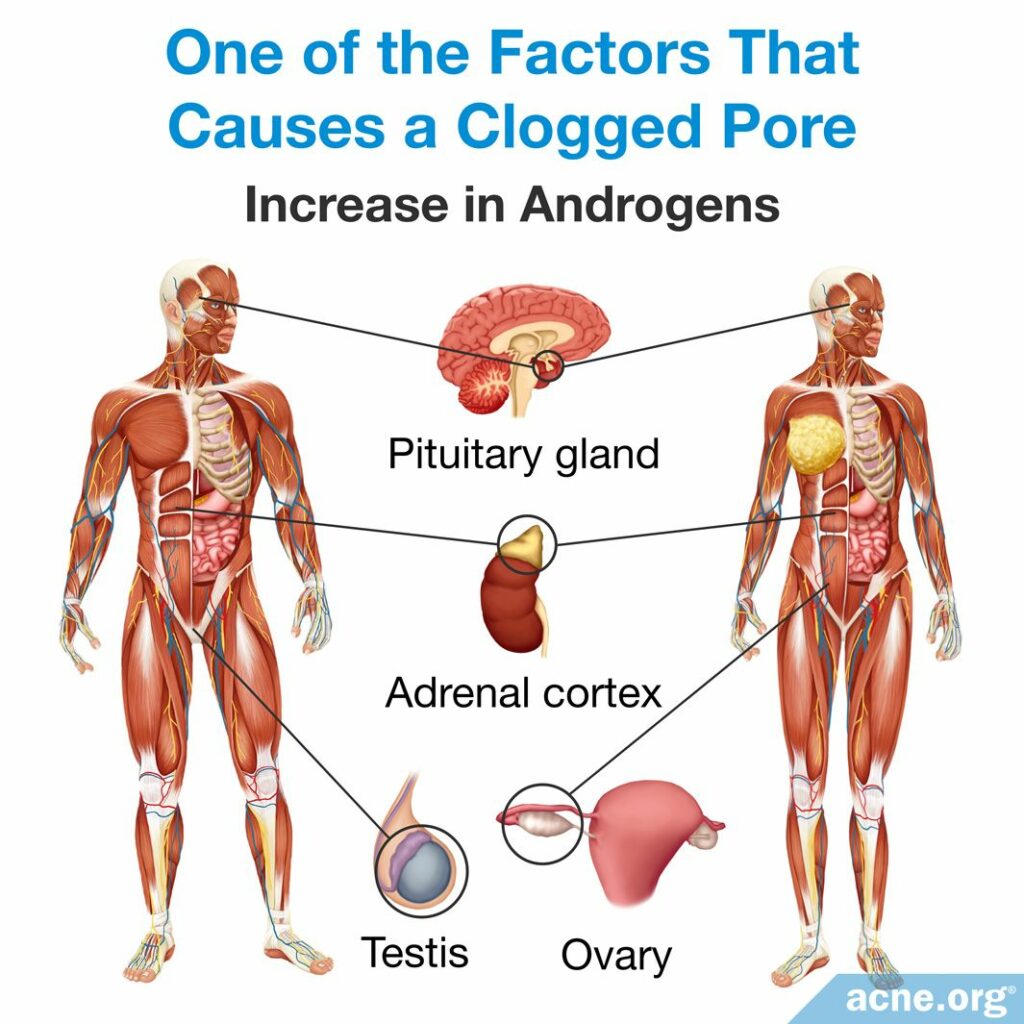

- An increase in androgens (male hormones present in both males and females) causes changes in the skin that promote clogged pores. For example, elevated androgen levels cause an increase in sebum production and in skin cell production, which can lead to a clogged pore. Puberty results in an increase in androgens, which also causes an increase in sebum. The increase in androgens explains why puberty often is the age of the onset of acne.

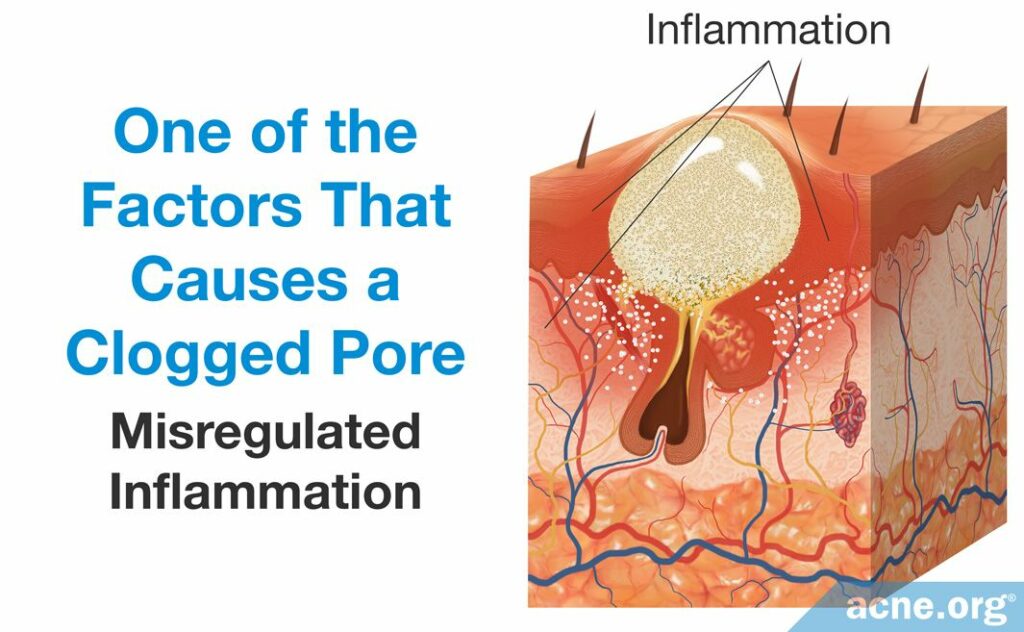

- Misregulated inflammation leads to an overgrowth of skin cells and the narrowing of a pore’s opening. Inflammation is the body’s normal defense mechanism. Controlled by the immune system, inflammation is a complex process that consists of immune-cells and immune system molecules, of which there are many types. Acne is considered to be an inflammatory disease, as inflammation is crucial to its development.

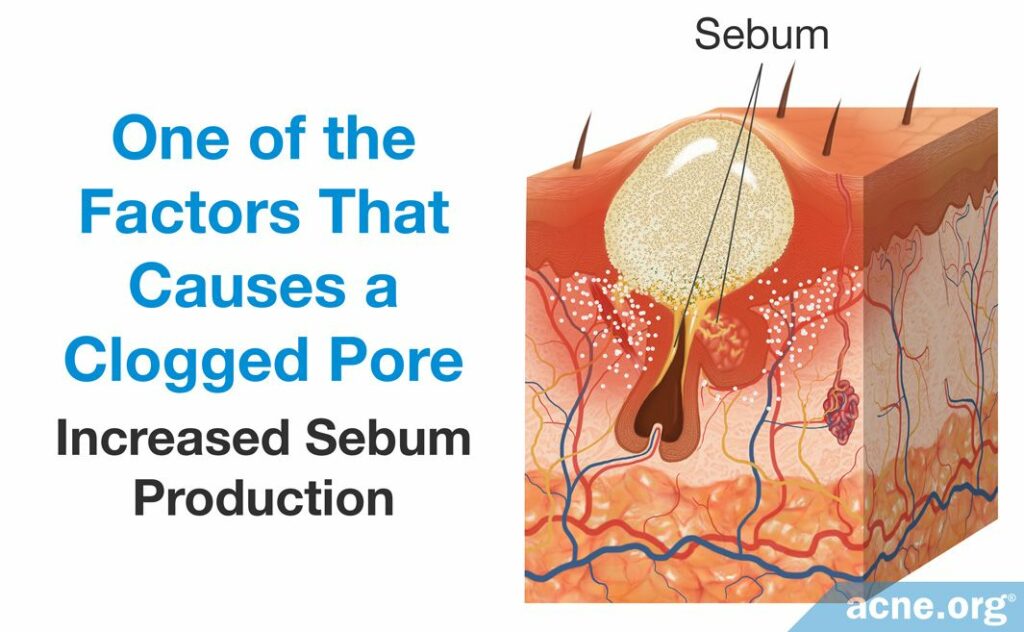

- An increase in sebum production may contribute to the overproduction of skin cells that narrow the pore’s opening. Sebum is produced by sebaceous glands, which are attached to the sides of follicles. The face and upper torso contain the largest sebaceous glands and are the regions that are most prone to develop acne.

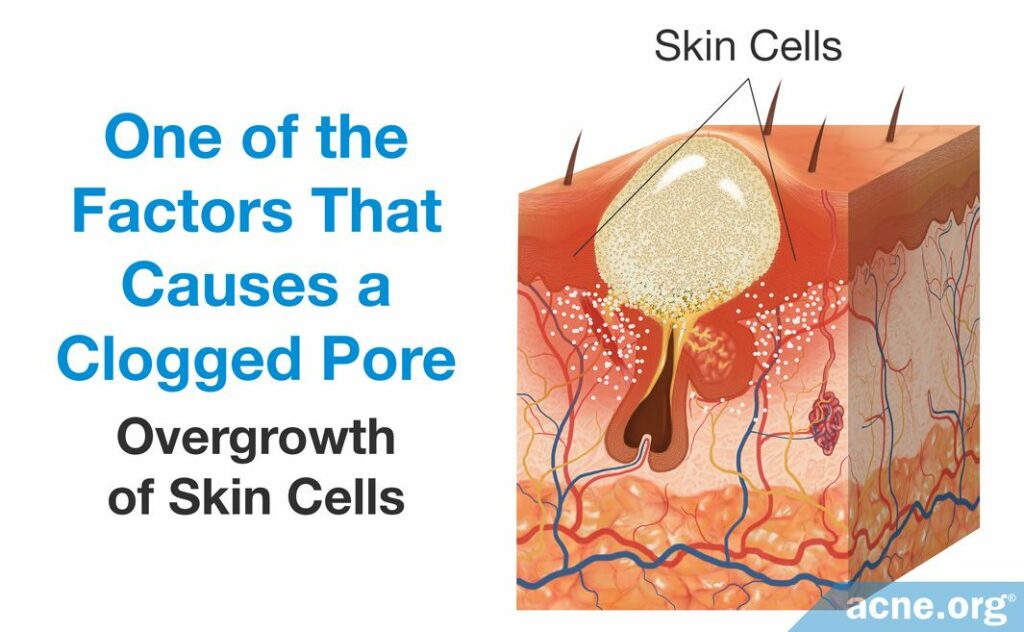

- An overgrowth of skin cells results in excess skin cells near the opening of the pore. The abundance of skin cells causes the top portion of the pore to narrow, which encourages clogging.

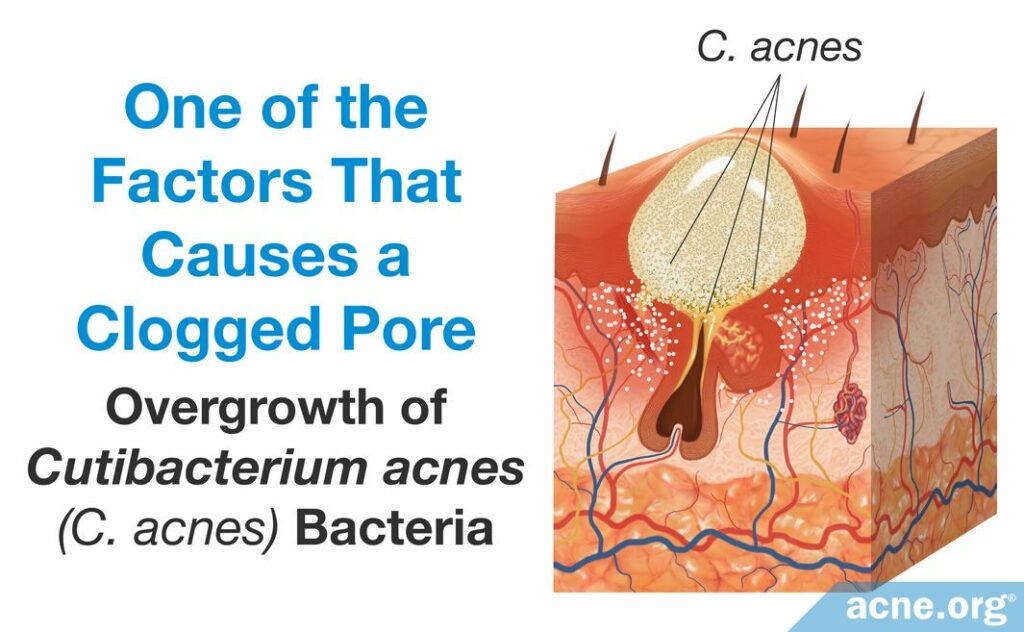

- An overgrowth of the bacteria, Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes), can worsen the inflammation of an acne lesion. C. acnes resides in the skin of people with and without acne and obtains its nutrients from sebum. When there is an excessive amount of sebum, however, C. acnes begins to overgrow, which produces an overabundance of byproducts of bacterial growth. These byproducts include proteins called proteases, hyaluronidases, and molecules called chemotactic factors. They are pro-inflammatory, meaning that they stimulate the immune system to respond and cause immune-cells to travel to the acne lesion. This worsens the inflammation characteristic of the acne lesion.1,2

Although acne researchers understand that these factors play a role in the development of acne, they do not know which factor leads to the next and ultimately creates an acne lesion. However, researchers have been able to sketch out the main steps of acne lesion development. Let’s have a close look.

Early Stages in Clogged Pore Development

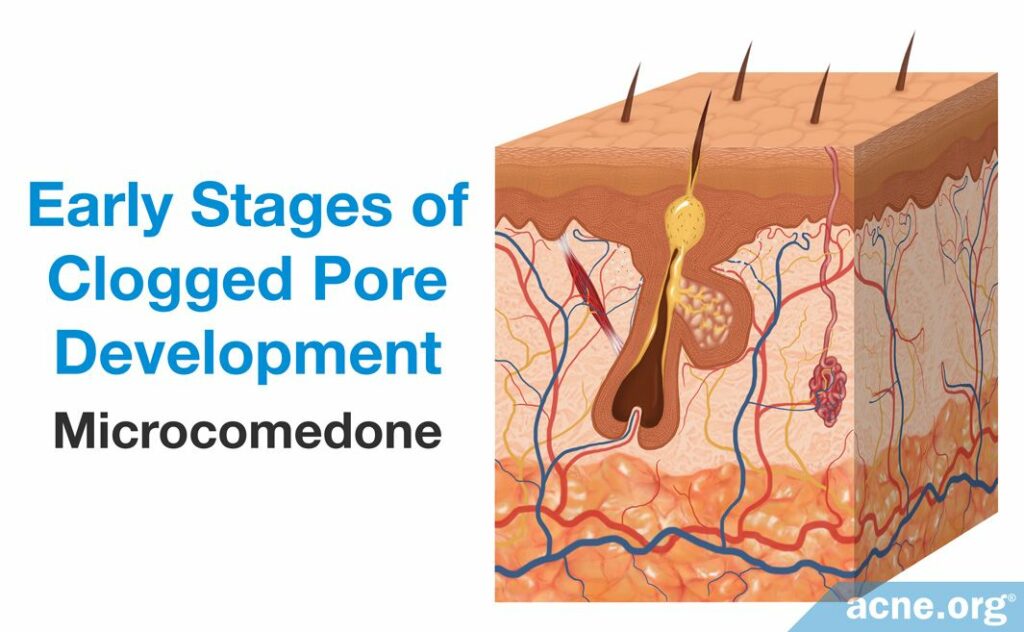

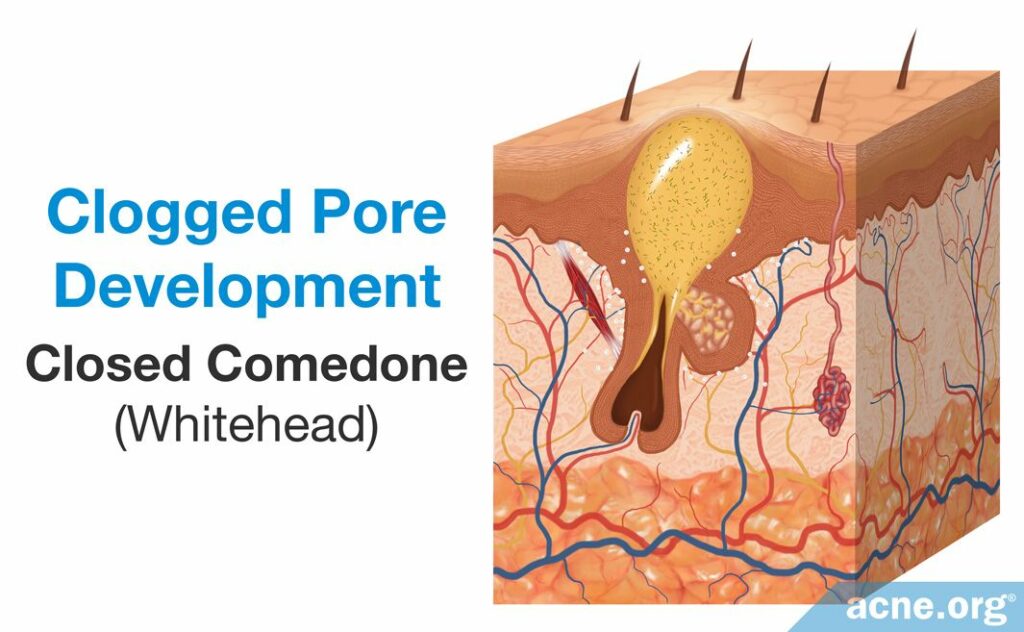

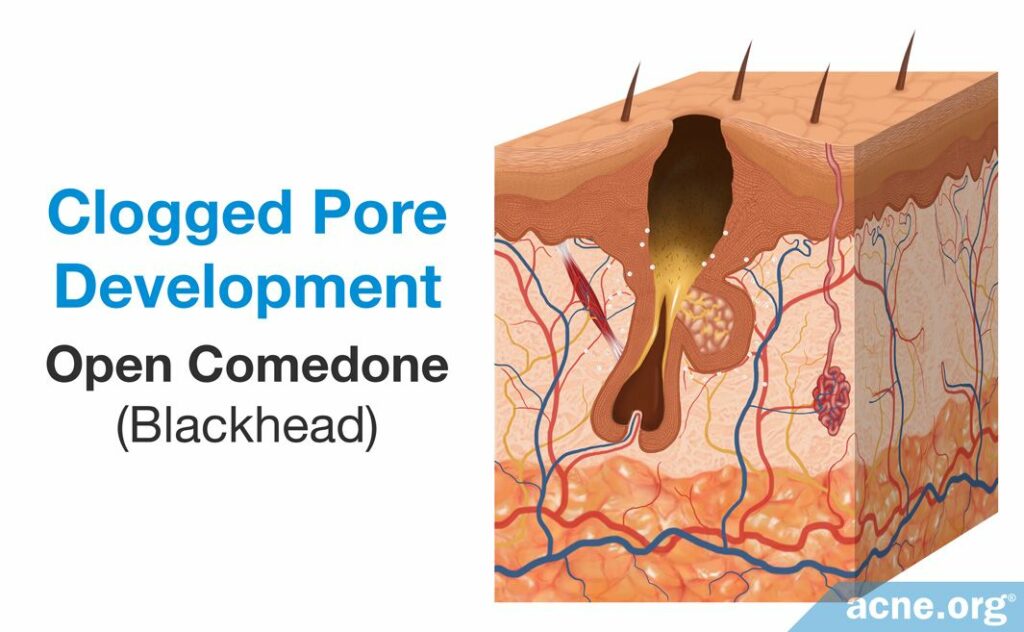

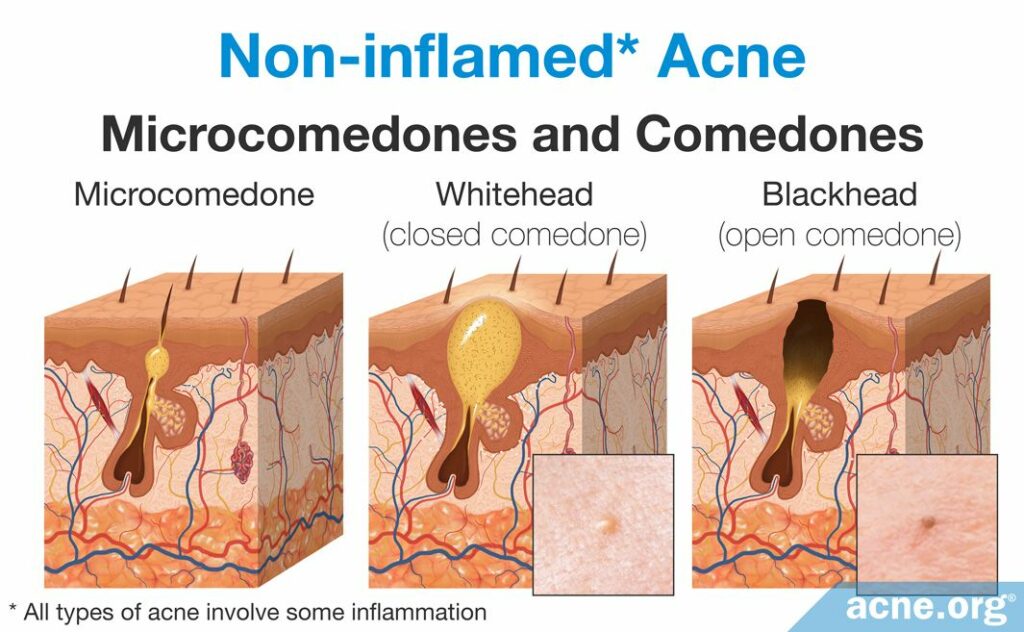

The first step in acne development is the formation of a microcomedone, which more commonly is known as a “clogged pore.” A microcomedone is small and cannot be seen with the naked eye. Its formation triggers a series of events that can block the escape of sebum, which normally drains to the surface, from the pore. Sometimes the microcomedone can become unclogged on its own. However, if it does not, the buildup of sebum causes the pore to swell, forming a comedone. Comedones are visible to the naked eye, and there are two types: closed comedones (whiteheads) and open comedones (blackheads).

- A closed comedone, also known as a whitehead, is a clogged pore that is blocked from releasing its contents onto the surface of the skin. The buildup of sebum and dead skin cells inside the pore results in visible white pus that appears at the surface of the pore.3

- An open comedone, also known as a blackhead, is a clogged pore that is partially blocked. There is a buildup of sebum and dead skin cells inside open comedones, but air can penetrate the pore. This oxygen chemically reacts with the sebum in a process known as oxidation, which causes the open comedone to appear dark brown or black like dirt.3

Comedones often are referred to as non-inflammatory lesions because they are neither red nor sore. They can heal on their own or can develop into other types of acne lesion that are red and sore, such as papules, pustules, nodules, and cysts. These lesions typically are often referred to as inflammatory lesions. Although these labels are useful in describing different types of acne, they are not scientifically correct, as research found that inflammation is present at the onset of acne formation, in the microcomedone. However, many people within dermatology still use these terms, and they are still helpful in differentiating the types of acne lesions.4

Now let’s delve deeper and look at how inflammation leads to a microcomedone, which then can develop into a comedone, an ultimately a papule, pustule, nodule, or cyst.

How Inflammation Is Involved in the Early Stages of Acne

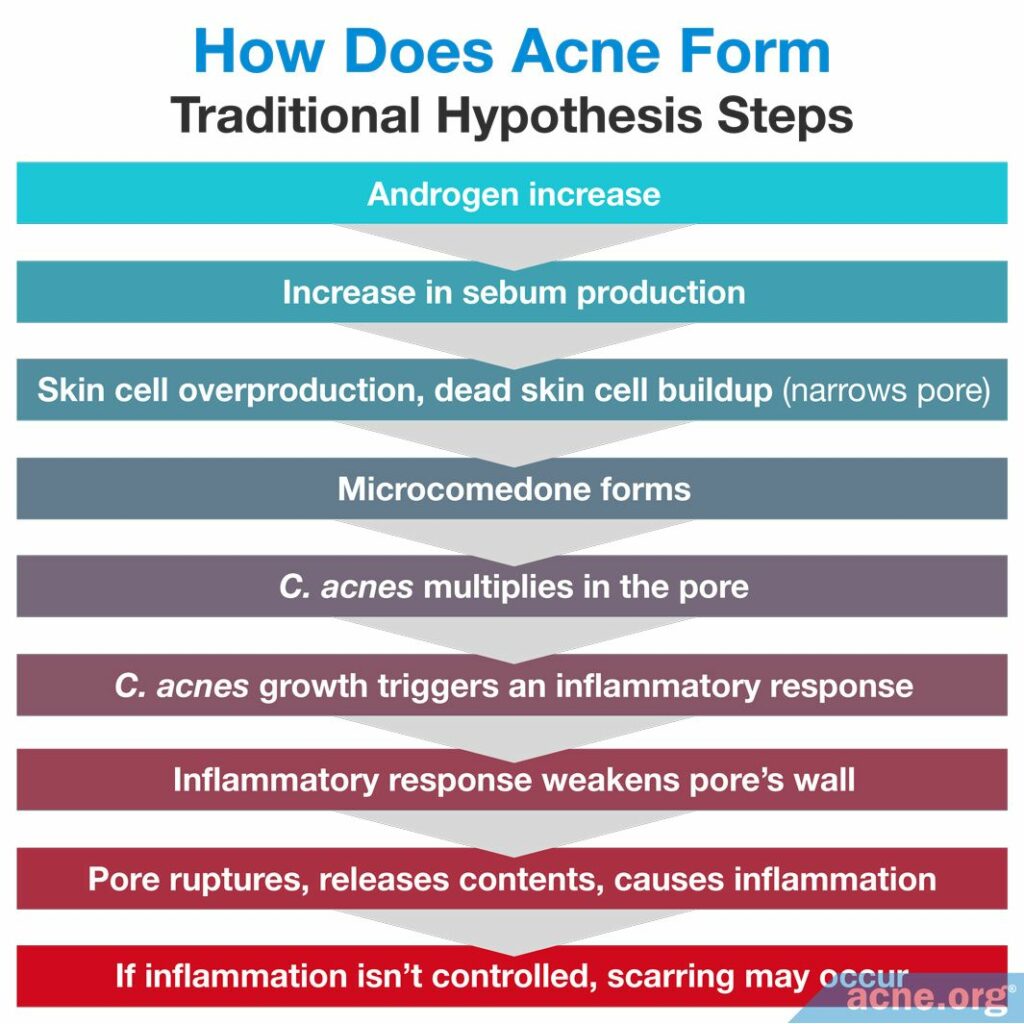

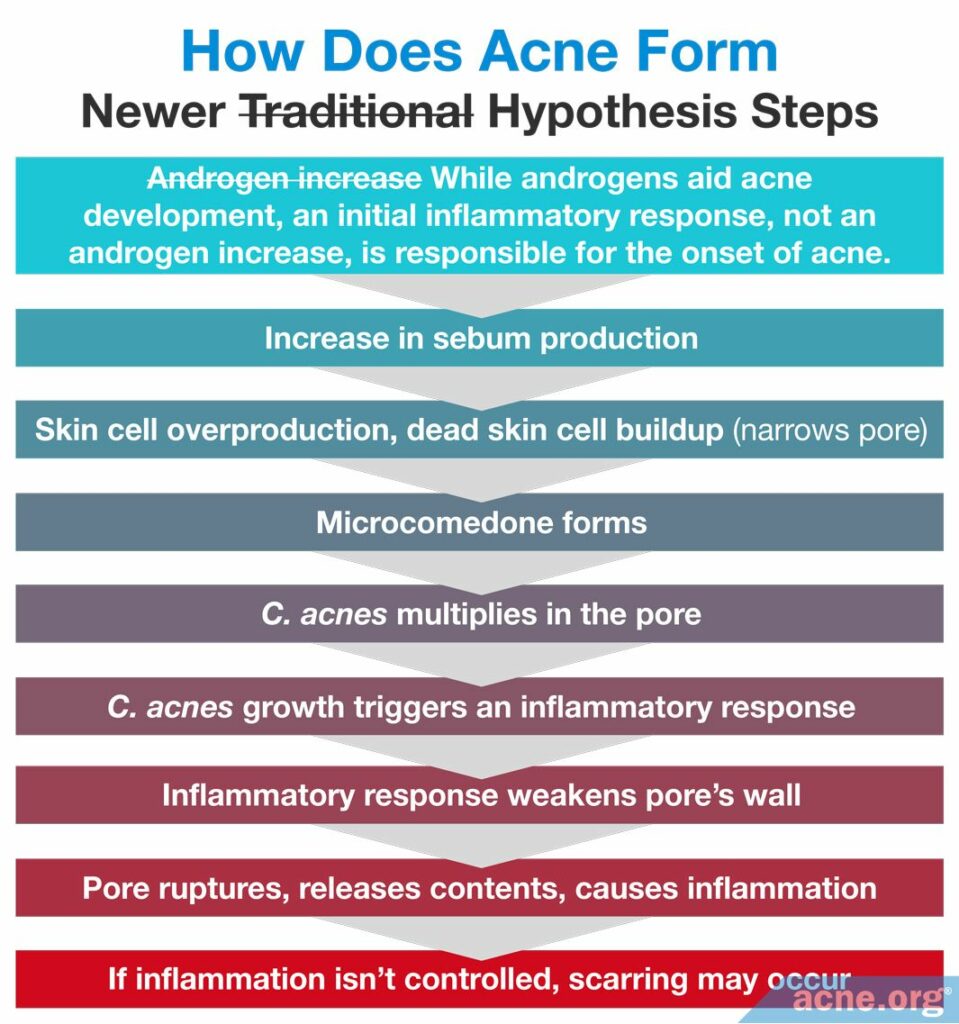

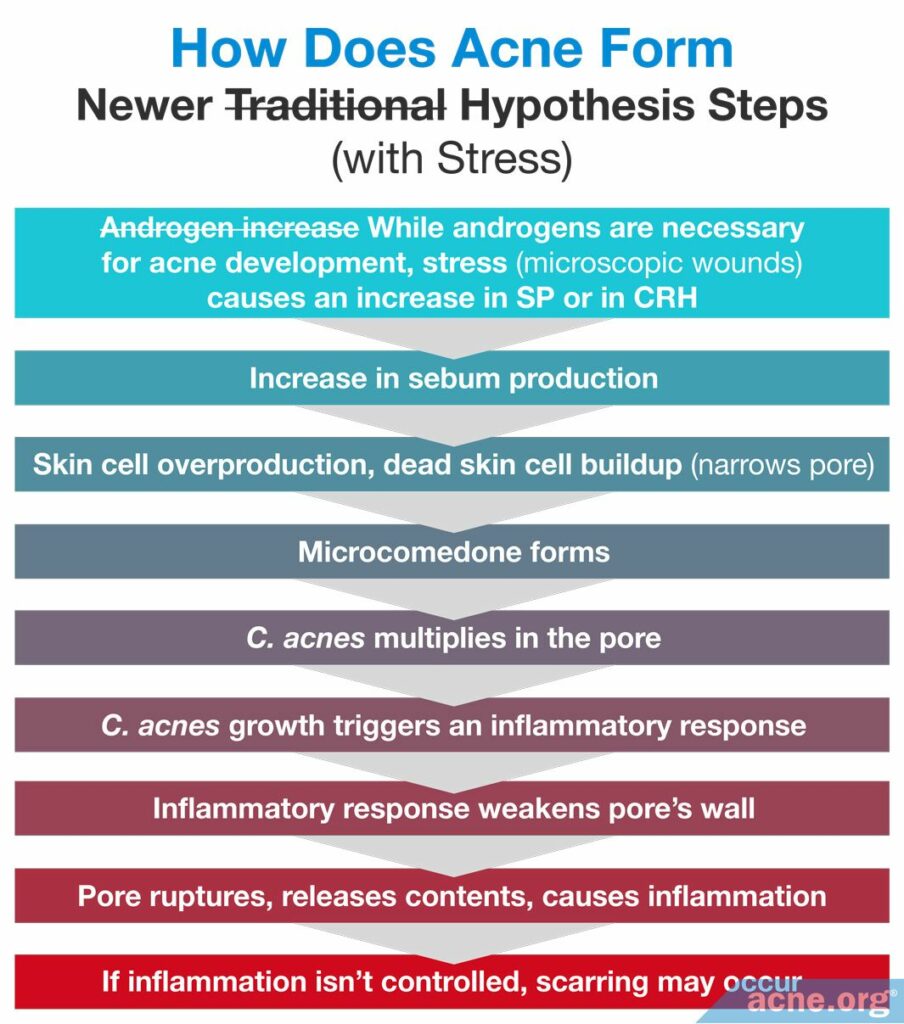

During the past decade, scientists reexamined and reformulated their idea of how acne develops. The older, traditional hypothesis stated that the overproduction of androgens, the male hormones found in both males and females, was the starting point of acne development. The newer hypothesis states that inflammation is the starting point.

Traditional hypothesis

Scientists first discovered androgens in 1936 and soon after realized their connection with acne. Research revealed that an elevation of androgens causes an excess production of sebum. Proponents of the traditional hypothesis believe that such sebum production leads to acne because it induces an overproduction of skin cells. Normally, skin cells constantly flake off of the skin and are replaced by new cells. However, the overproduction of new skin cells combined with a buildup of dead skin cells can narrow the opening of the pore, making it prone to clog: this then leads to the formation of a microcomedone.

According to the traditional hypothesis, the progression from a microcomedone to a comedone is triggered by the presence and growth of C. acnes bacteria. Inside a clogged pore, there is little to no oxygen, and C. acnes thrives in environments with an abundance of sebum but little to no oxygen and therefore begins to reproduce rapidly. This overgrowth stimulates the immune system to begin an inflammatory response. Specifically, C. acnes stimulates the immune system by releasing proteins and other molecules that recruit immune-cells and inflammatory molecules to the site of a clogged pore. Once the inflammatory response begins, C. acnes then can bind to a special protein on the surface of skin cells and immune system cells called toll-like receptor 2 (TLR-2) and trigger an even stronger inflammatory response. This strong and often excessive inflammatory response can weaken the follicle’s wall.

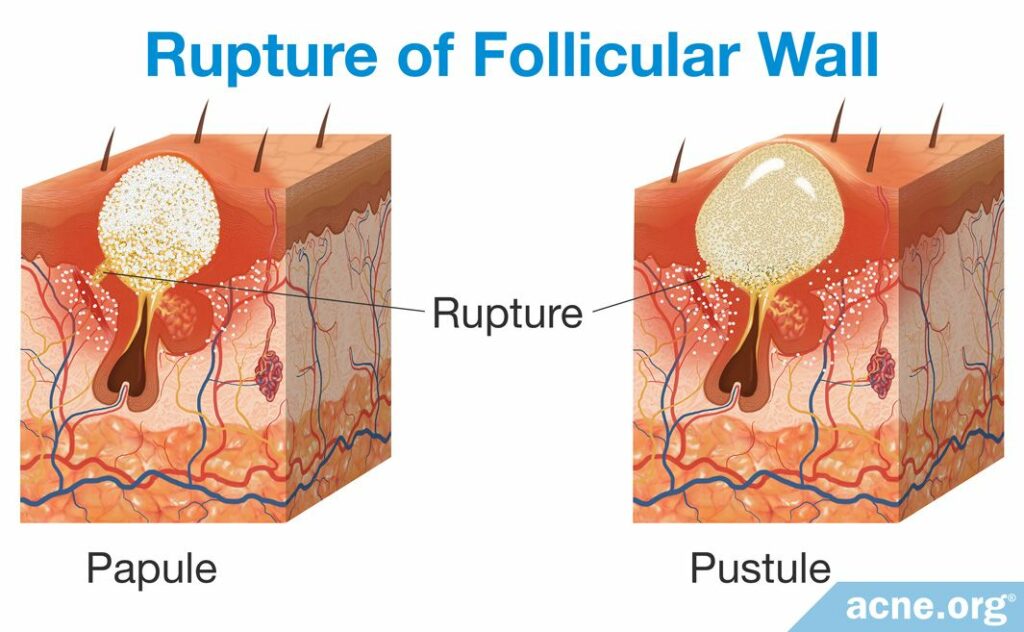

The inflammation eventually causes the follicle wall to rupture, releasing the contents of the pore into the surrounding tissue. The body reacts to these contents as if they were foreign invaders and steps up inflammation even further. An inflamed papule forms if only a small portion of the pore wall breaks. If the pore collapses, a nodule or cyst can form. If the inflammation inherent to these inflamed lesions is not controlled, it can lead to acne scarring and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (dark/red marks left over once the lesion heals).

Newer hypothesis

As research continued into acne, it was discovered that inflammation is present much sooner than was originally suspected. The following studies show us these discoveries.

Expand to read details of studies

Scientists began questioning the traditional hypothesis once a 1988 study published in the British Journal of Dermatology found inflammation is present in microcomedones. This is much earlier than the traditional hypothesis’s idea that inflammation becomes present only after C. acnes overgrowth. Specifically, the study found that inflammation is present as early as six hours from the onset of a microcomedone. However, the study found also that the inflammation present in the microcomedone differs from the inflammation of a more developed acne lesion. Particularly, T cells, which are recruited at the onset of infection, were present in the microcomedone, whereas neutrophils, which are responsible for fighting off bacteria, were present later in acne lesions.5 This research was confirmed by a similar study published in 2003 in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.6

A separate 2008 study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology found additional clinical evidence that inflammation is the initial trigger of acne. To perform the study, the researchers observed acne development in 25 patients over the course of 12 weeks. They did so by taking special high-resolution photographs of the participants’ faces every two weeks during the study-period. The researchers used the photographs to follow the progression of 329 inflammatory acne lesions from first appearance to resolution in order to identify how the lesions developed and healed over time. At study completion, they found that inflammation was present even in microcomedones. They concluded that “inflammation could be a primary event rather than a secondary process in the development of acne.”7

This led to a newer hypothesis that puts inflammation sooner in the chain of events that lead to acne. Although this newer hypothesis states that inflammation is one of the earliest factors involved in acne lesion formation, it includes the other factors traditionally associated with acne, including excessive sebum, overproduction of skin cells, and C. acnes overgrowth.

Although scientists learned that inflammation is the trigger for acne, they have not identified what causes this initial inflammation. In an effort to identify what causes it, scientists put forward two proposals: the elevated base inflammation proposal and the stress proposal.

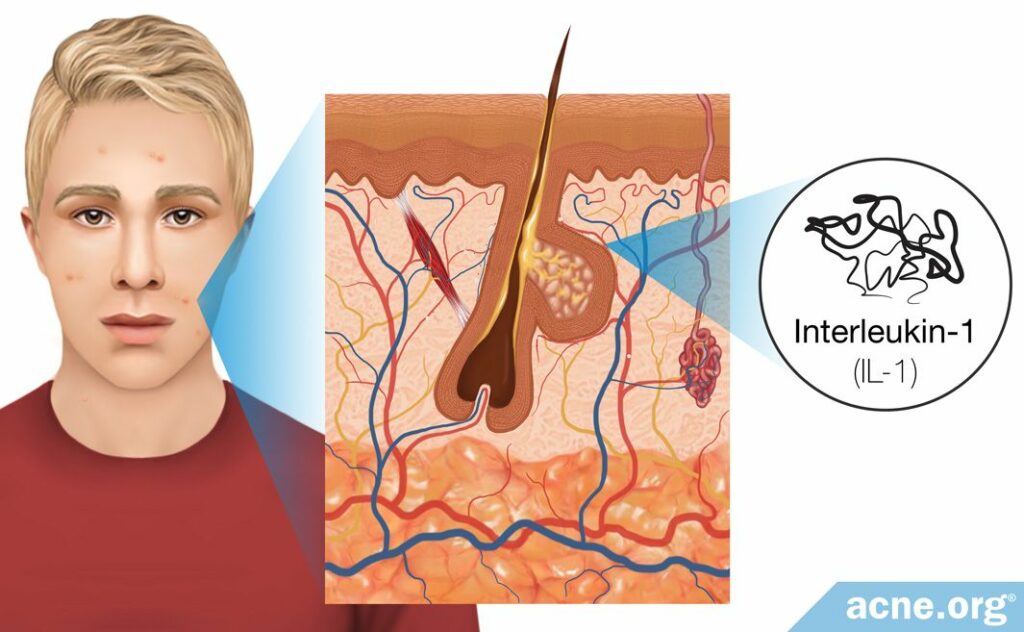

Elevated base inflammation proposal

As stated, scientists have not identified what causes the initial inflammation inherent to microcomedones. To explain how inflammation may trigger acne development, some researchers proposed that a low level of inflammation consistently is present in the skin to keep the skin cells alert and prepared to respond to bacteria that may try to enter the body or damage the skin. This means that a small level of inflammation always is present in the skin. However, this proposal suggests that in the skin of acne-prone people the baseline level of inflammation is higher than in the skin of those who are not prone to acne, and this higher level of inflammation is what causes some people to develop acne.

In support of the proposal that a low level of inflammation always is present in the skin, scientists performed two studies that found there are at least two immune-molecules elevated in the skin of acne patients: interleukin-1 (IL-1) and defensins.

Expand to read details of studies

A 1992 study published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology looked into whether the presence of IL-1 is responsible for this early inflammation around clogged pores. IL-1 is a molecule that consistently is present in healthy skin but is elevated in acne patients. The study found that one reason skin cells produce IL-1 might be to keep the skin alert and ready to respond to anything that could harm or damage the skin. Because of the study-design, the researchers were not able to examine the inflammation at the site of microcomedones. However, they were able to find that IL-1 is especially elevated in and around comedones. The importance of this finding was that IL-1 is one of the earliest inflammatory molecules present at the site of a clogged pore, which the researchers predicted was one of the triggers of the initial inflammation. Therefore, they believed that IL-1, although present at low levels in all skin types, is elevated in acne patients and that this elevation could be the initial trigger of inflammatory acne.8

A 2001 study published in the same journal found additional molecules called defensins, which act similarly to IL-1, also were present at the site of comedones. As with IL-1, defensins normally are present in all skin types at low levels but can become elevated in the skin of acne patients. The elevated levels of defensins may contribute to the initiation of the inflammatory response.9

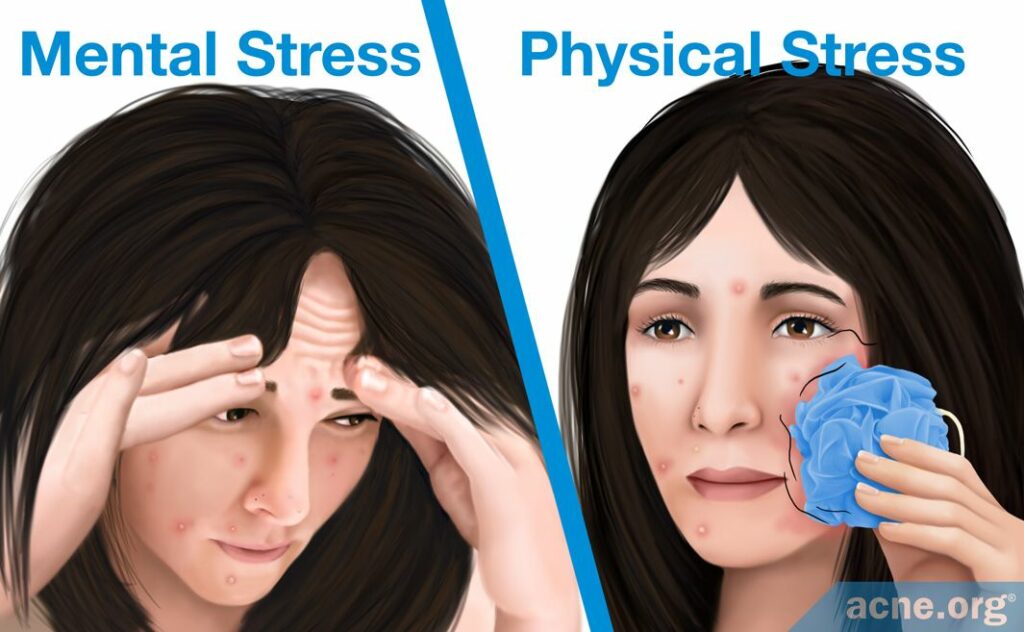

Stress proposal

A second explanation of what triggers the initial inflammation in acne patients proposes that stress may be partially responsible for triggering the inflammatory response at the site of microcomedones. Typically, stress is defined as a state of mental anxiety, but the body’s stress response can be triggered also by physical stress caused by small wounds. For the skin, this entails friction, scrubbing, and harsh cleansing. Scientists found that physical stress can lead to inflammation by causing neuropeptides (substance P) and hormones to assemble, although there likely are other ways that scientists have not discovered.

- Neuropeptides (substance P): Neuropeptides are short protein fragments produced by the body’s nervous system. There are thousands of neuropeptides in the body that trigger a variety of responses, but scientists found that only one called substance P (SP) may be associated with stress, inflammation, and acne. SP’s normal function in the body is to trigger the inflammatory response in the nervous system. Nerve cells can release it in response to physical stress from friction, scrubbing, and cleansing. When this occurs, SP promotes the production of several inflammatory molecules. However, when this substance triggers inflammation in the skin, it also may trigger the development of acne. Research found that the levels of SP are elevated in the acne lesions that are comedogenic (whiteheads and blackheads). This suggests that physical stress can damage the skin and may result in the release of SP, which may trigger the inflammatory response in a microcomedone.1

- Hormones (corticotropin-releasing hormone): Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is a hormone released normally by the nervous system in response to stress, and research found that it is elevated in acne lesions. Scientists found that CRH always is the first hormone released in response to stress. Its role is to coordinate the hormonal and immune response to stress. In the skin, physical stress caused by friction, scrubbing, or cleansing can trigger the release of CRH, which then can stimulate inflammation that attempts to heal the skin. This inflammation may contribute to the formation of a microcomedone.1,10

Although we need more research to confirm the connection between stress, inflammation, and acne, it is possible that stress results in the release of neuropeptides and hormones that trigger inflammation in an early acne lesion.

Now that we know the possible ways that inflammation is involved in the formation of a microcomedone, let’s look at the other factors involved in forming a microcomedone, and how that initial clogged pore can turn into a non-inflammatory lesion.

Formation of Non-inflammatory Acne Lesions: Microcomedones and Comedones

Excessive skin cell growth in the pore, called follicular hyperkeratinization, combined with excessive sebum production, called seborrhea, as well as changes in the composition of the sebum, lead to clogged pores.

Follicular hyperkeratinization

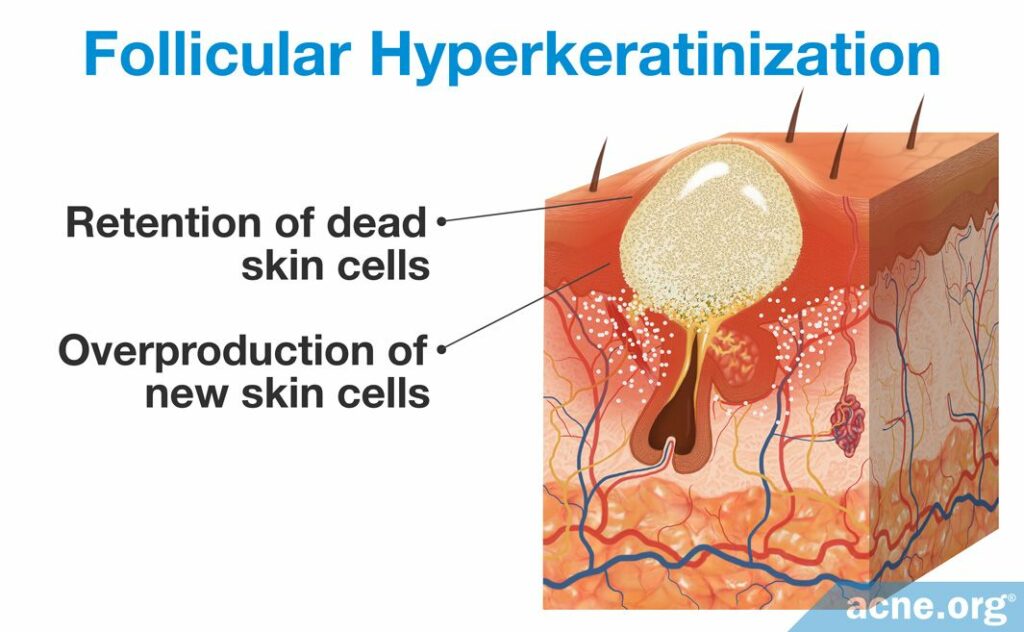

A microcomedone is formed in a process called follicular hyperkeratinization, which consists of two changes to the skin: the overproduction of new skin cells and the retention of dead skin cells.

- The overproduction of new skin cells inside of a pore results in a buildup of skin cells toward the top. This overproduction occurs because the skin cells divide rapidly. Multiple studies examined the production of keratin 6 and 16, two proteins that signify skin cell division. They found that microcomedones and comedones possess increased levels of keratin 6 and 16, suggesting that a high level of cell division occurs in these pores. When more skin cells are produced than the skin needs, thickening of the pore results, which narrows its opening.1,2,11,12

- The retention of dead skin cells toward the top of the pore results in a buildup of dead skin cells inside the pore. Normally, dead skin cells flake off the wall of the pore. However, sometimes they begin to stick to the wall of the pore, sticking to one another instead of flaking off. The stickiness of the dead skin cell is regulated by two proteins called desmosomes and keratin, which function similarly to glue.11

Essentially, an overproduction of new skin cells results in the thickening of a pore and an increase in dead skin cells that do not flake off the inside. Both of these processes result in a narrowed opening of the pore. No one knows what causes follicular hyperkeratinization, but several factors, including hormones, IL-1, and sebum, may contribute.

When follicular hyperkeratinization occurs, the pore becomes so narrow that the sebum no longer can drain to the surface of the skin.1,11

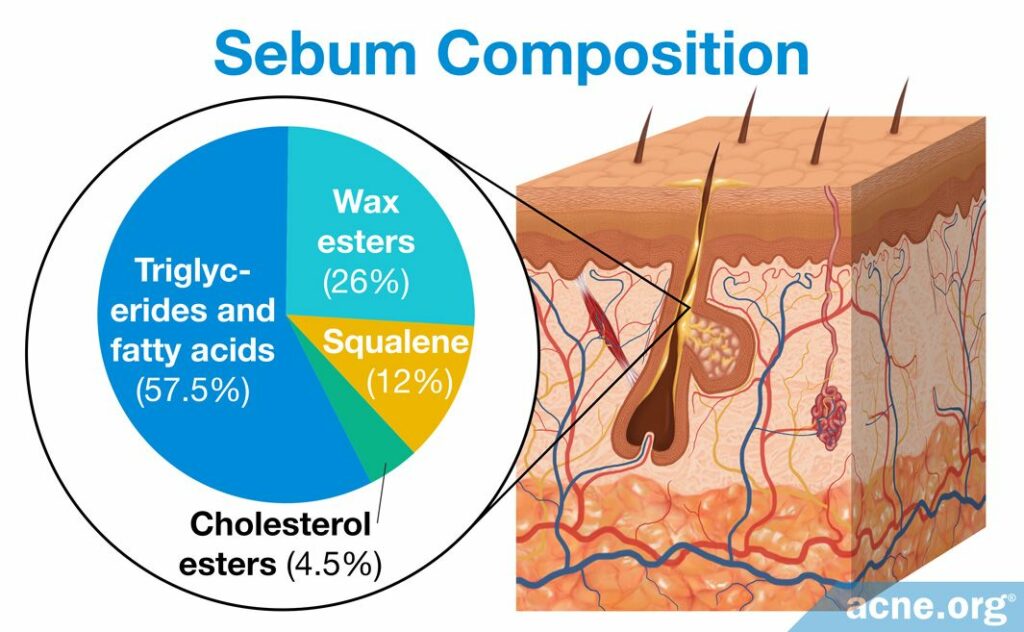

Seborrhea and changes in sebum composition

Follicular hyperkeratinization leads to the formation of a microcomedone, but sebum transitions a microcomedone into a comedone. The most well-known process by which sebum forms a comedone is through seborrhea, which is excessive sebum production and is thought to contribute to follicular hyperkeratinization. Once follicular hyperkeratinization narrows the pore opening, it becomes difficult for the sebum to drain onto the surface of the skin. When sebum does not drain, it begins to build up in the pore, leading to the formation of a visible closed comedone (whitehead) or open comedone (blackhead).

Scientists found that changes in the compounds that make up sebum also may play a role in microcomedone formation. Specifically, research found that there are differences in the sebum of acne patients and non-acne patients. Sebum normally is composed of a variety of lipids, which are molecules with oil-like properties. There are hundreds of different lipids in the human body, but sebum predominantly comprises squalene, wax esters, triglycerides, fatty acids, cholesterol esters, and free cholesterol. The concentrations of these lipids can differ widely between people with and without acne.2 Two main differences between the sebum of acne patients and sebum of non-acne patients are levels of linoleic acid (linoleate) and production of squalene peroxide.

- The levels of linoleic acid, which is a fatty acid lipid, differs drastically between acne and non-acne patients. In healthy individuals, it makes up, on average, 45% of the fatty acids found in sebum. In acne patients, however, lineolate comprises generally only 6%. When acne medications such as isotretinoin are used to treat acne and excess sebum, and sebum levels decrease, the percentage of lineolate returns to normal. While it still is uncertain if and how this lower percentage of linoleic acid leads to acne, research shows that the lower percentage in acne patients may trigger follicular hyperkeratinization and thus the formation of a microcomedone.2,13

- The production of squalene peroxide in sebum may stimulate follicular hyperkeratosis, which can block the opening of a pore and cause a microcomedone to form. Squalene is a lipid normally found in sebum, but C. acnes in a pore can convert it into squalene peroxide. Squalene itself does not clog pores, but squalene peroxide is highly comedogenic, meaning that it is well known to clog pores. Further, squalene peroxide can induce an inflammatory response, increasing inflammation in the pore.1,14,15

Now that we know how a comedone forms, let’s look at the next stage of acne development, where a non-inflammatory comedone becomes an inflammatory papule, which fills with pus to become a pustule.

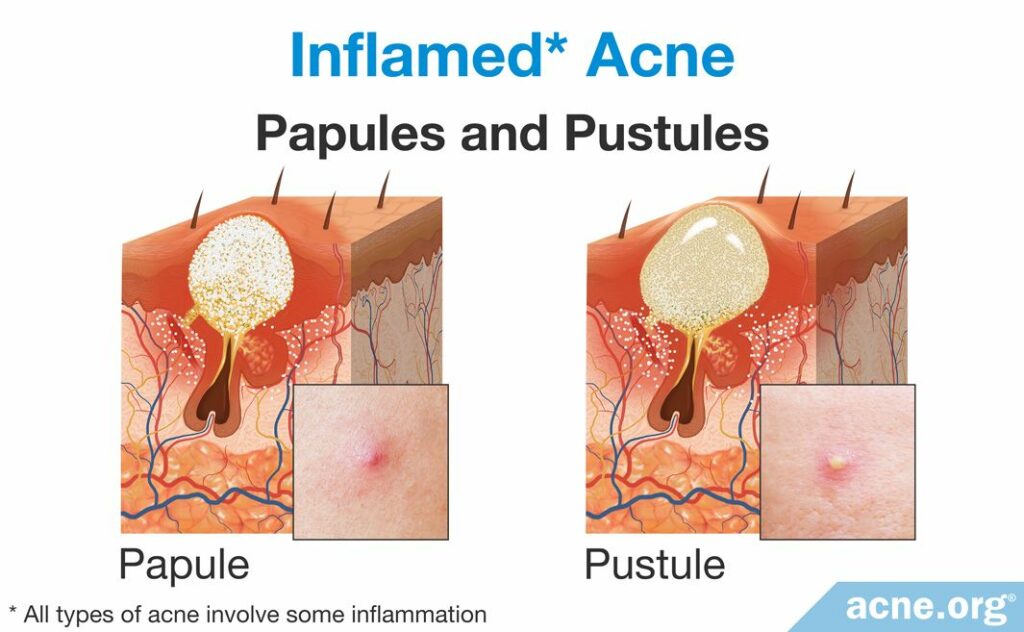

Formation of Inflammatory Acne Lesions: Papules and Pustules

Papules and pustules are the two most common types of acne lesion that scientists traditionally have classified as “inflammatory.” A papule is a red elevated lesion with a diameter up to 5mm that contains no white or yellow center. A papule turns into a pustule once a collection of white or yellow pus fills the pore and accumulates at the surface of the lesion. People refer to pustules often as “pimples” or “zits.”11,13 Most papules and pustules develop from a comedone, though sometimes they skip the comedone stage and develop directly from a microcomedone. As the majority of inflammatory acne lesions go through a comedonal stage before becoming an inflammatory lesion, let’s examine the steps that occur to develop a comedone into an inflammatory lesion.

Overgrowth of C. acnes and formation of a papule

Microcomedones develop from microscopic changes in the pore. Specifically, as we have seen, follicular hyperkeratinization combined with seborrhea and changes in sebum composition narrow the opening of a pore. This leads to a buildup of sebum inside the pore. Because the pore is clogged, oxygen levels within drop. The high-sebum and low-to-no oxygen environment provides for an ideal environment for the growth of the bacterium, C. acnes. In such an environment, C. acnes grows and divides quickly, which affects the pore in three ways.

- The growth of the bacteria builds pressure inside the pore.

- C. acnes produces factors that can affect the pore,9 including:

- Pro-inflammatory chemotactic factors, which can recruit immune cells and worsen inflammation inside the pore. When C. acnes releases chemotactic factors, the chemotactic factors recruit immune-cells, such as neutrophils, to the pore. Neutrophils are the most abundant white blood cells, and their role is to kill bacteria. Once inside the comedone, neutrophils begin to kill C. acnes, which causes it to release additional enzymes that recruit more cells and further worsen inflammation.14,15

- Follicular irritants, including proteases and hyaluronidases, are proteins that interact with the follicular wall and stimulate inflammation of the follicle wall and surrounding the follicle. Follicular irritants can cause inflammation both inside the follicle and outside the pore in the surrounding tissue. The aim of this inflammation is to kill off the C. acnes growing inside the pore. However, these irritants can worsen the inflammation associated with acne.14

- Additionally, C. acnes can bind to a special protein on the surface of skin and immune-cells called toll-like receptor 2 (TLR-2). When this happens, C. acnes triggers the cells to release additional inflammatory molecules, such as interleukin-8 (IL-8), which recruits additional neutrophils to the pore. The addition of IL-8 and more neutrophils to the already worsened inflammation in and around the pore wall creates too large of an inflammatory response for such a small pore to handle. The infiltrating neutrophils cause the pore to continue to swell until it no longer can sustain the amount of inflammation present, and the follicle ruptures. When the pore ruptures, it releases its contents, including the trapped sebum, C. acnes, inflammatory molecules, dead skin cells, and neutrophils, into the surrounding tissue. The body responds to this “invasion” by recruiting more immune-cells and expanding the inflammation beyond the follicle. When this occurs, the lesion becomes red and sore and is called a papule.14,15

From papule to pustule

Once a pore ruptures, the release of the pore’s contents into the surrounding tissue causes the body to react with inflammation, which is experienced as redness and soreness around an acne lesion. This initial red and sore lesion, which it not yet filled with pus, is called a papule. Sometimes a papule spontaneously heals, but most often, over the course of approximately two days, a collection of white or yellow pus fills the pore and accumulates at the surface of the lesion, and a pustule is born.15,17

How pus is formed: The rupture of the follicle triggers the infiltration of immune-cells, including neutrophils, to the area surrounding the pore in order to repair the damage caused from the rupture. However, repairing the ruptured follicle is dangerous for neutrophils, and many become damaged and die in the process. When neutrophils die, other immune-cells called phagocytes attempt to consume the dead neutrophils in order to remove them from the inflamed area but quickly are overwhelmed and cannot handle such a number of neutrophils. The products of the dead, consumed neutrophils combined with the fluid that appears at the site of inflammation produces the pus. In other words, the remains of dead neutrophils that accumulate over a two-day period become the pus that is present in the pustule.17 A pustule releases its contents either onto the skin surface naturally or through a person “popping” the lesion, or the body absorbs the pus and heals the lesion.

As we have seen, if a pore ruptures, a papule forms, which then fills with pus to become a pustule. However, sometimes, a pore does not rupture only in small area, and instead, completely explodes deep within the skin. In that case, a severe acne lesion can result. Let’s look at how this occurs next.

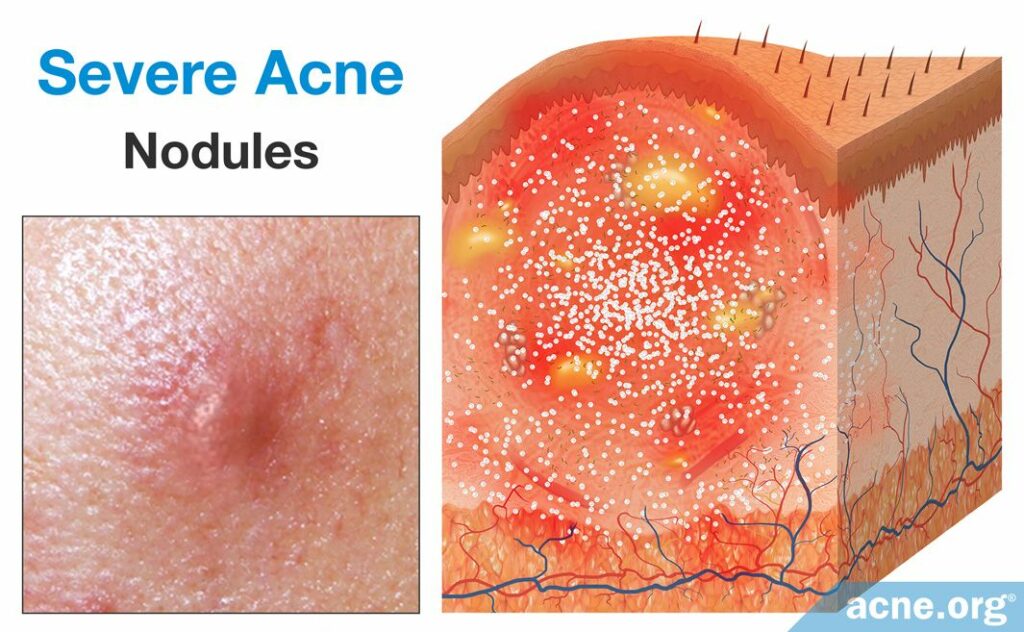

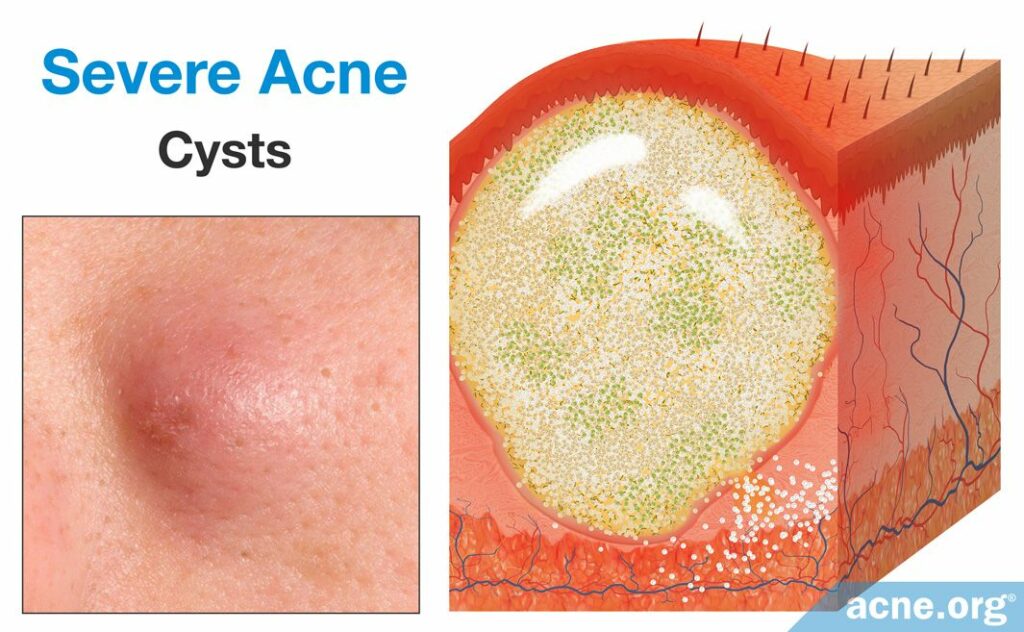

Severe Acne

The two most severe types of acne lesion are nodules and cysts. They often result in severe tissue damage, which frequently leads to scarring of the skin.

Nodules are by far the most common form of severe acne lesion. They develop from comedones. Like a papule, nodules are inflammatory lesions that are caused when the follicle wall ruptures. But unlike a small rupture that leads to a papule, sometimes a pore explodes, rupturing extensively and deeply in the skin. Because the follicle ruptures in such an extreme manner, the body produces an even larger inflammatory response, and the development of a large, fibrous, and painful lesion over 5mm in diameter. Similarly to papules, nodules are not filled with pus. However, unlike papules, nodules do not normally become filled with pus. Because of the large size and excessive inflammation of a nodule, it requires more time to heal.18

Cysts are rare lesions that differ from nodules because they are filled with pus. However, unlike pustules, the pus of a cyst is surrounded by a lining that keeps the pus and pore contents from being expelled onto the surface of the skin or from healing naturally. Cysts form once the follicular wall ruptures in a small area, but instead of inflammation clearing the debris of the pore, a secondary wall forms around the expelled follicular contents. This secondary wall is thick, strong, and present deep within the skin. True acne cysts are rare because they have a full lining, which completely separates its contents from the surrounding skin, and the contents are non-inflammatory in nature. Even though there is a full lining, an acne cyst allows for inflammatory substances and pus to fill it. Therefore, acne cysts would be best described as abscesses.10,19

References

- Tanghetti, E. The role of inflammation in the pathology of acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 6, 27 – 35 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3780801/

- Cunliffe, W. et al. Comedone formation: Etiology, clinical presentation, and treatment. Clin Dermatol 22, 367 – 374 (2004). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15556720

- Brogden, R. & Goa, K. Adapalene. Drugs 53, 511 – 519 (1997). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9074847

- Oberemok, S. & Shalita, A. Acne vulgaris, I: Pathogenesis and diagnosis. Cutis 70, 101 – 105 (2002). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12234155

- Norris J. F., Cunliffe, W. J. A histological and immunocytochemical study of early acne lesions. Br J Dermatol 118, 651 – 659 (1988). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2969256

- Jeremy, A. H., Holland, D. B., Roberts, S. G., Thomson, K. F. & Cunliffe, W. J. Inflammatory events are involved in acne lesion initiation. J Invest Dermatol 121, 20 – 27 (2003). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12839559

- Do, T. et al. Computer-assisted alignment and tracking of acne lesions indicate that most inflammatory lesions arise from comedones and de novo. J Am Acad Dermatol 58, 603 – 608 (2008). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18249468

- Ingham, E., Eady, E. A., Goodwin, C. E., Cove, J. H. & Cunliffe,W. J. Pro-inflammatory levels of interleukin-1 alpha-like bioactivity are present in the majority of open comedones in acne vulgaris. J Invest Dermatol 98, 895 – 901 (1992). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1534342

- Chronnell, C. M. et al. Human beta defensin-1and -2 expression in human pilosebaceous units: upregulation in acne vulgaris lesions. J Invest Dermatol 117, 1120 – 1125 (2001). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11710922

- Acne vulgaris. En.wikipedia.org (2017). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acne_vulgaris

- Thiboutot, D. The role of follicular hyperkeratinization in acne. J Dermatol Treat 11, 5 – 8 (2000). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/095466300750163645

- Kurokawa, I. et al. New developments in our understanding of acne pathogenesis and treatment. Exp Dermatol 18, 821 – 832 (2009). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19555434

- Gollnick, H. Current concepts of the pathogenesis of acne. Drugs 63, 1579 – 1596 (2003). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12887264

- Degitz, K., Placzek, M., Borelli, C. & Plewig, G. Pathophysiology of acne. JDDG 5, 316 – 323 (2007). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17376098

- Toyoda, M. & Morohashi, M. Pathogenesis of acne. Med Electron Microsc 34, 29 – 40 (2001). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11479771

- Zouboulis, C. et al. Acne is an inflammatory disease and alterations of sebum composition initiate acne lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol 28, 527 – 532 (2014). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24134468

- Puss. En.wikipedia.org (2017). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pus

- Acne Vulgaris. En.wikipedia.org (2017). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acne_vulgaris

- Buxton, P. ABC of Dermatology (4th ed). 49 (Blackwell Publishing, 2003). https://www.scribd.com/document/340585968/PK-Buxton-ABC-of-Dermatology-4th-Ed-2003

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products