Currently, There Is No Evidence That Fatty or Oily Foods Cause or Worsen Acne

The Essential Info

Increased production of skin oil, which is made of different types of fat, contributes to acne. Since skin oil is made of fats, and some foods contain fats, researchers wonder if fatty and oily foods are linked to acne.

The answer is not clear. Current research on the relationship between fatty foods and acne is limited.

Further confounding the topic is the presence of both good and bad fats in foods. Good fats like omega-3s could be beneficial for acne, while bad fats like saturated fats could prove detrimental.

Furthermore, since fatty food contains more calories, it could be the calorie content in fatty food, and not the fat itself in the food, that would lead to an increase in acne symptoms.

The Bottom Line: At this time, there is no conclusive relationship between the amount or type of fat in the diet and acne. However, it makes sense to eat more omega-3 fats and unprocessed foods, and avoid fast food and other foods high in processed fats and oils.

The Science

- Types of Fat

- Can Eating Fat Increase Skin Oil Production In the Skin and Lead to More Acne?

- High-Calorie Content of Fatty Foods

- Surveys Investigating the Potential Link Between Fatty Foods and Acne

You may have heard someone say before that “fatty food causes acne.” But this sort of blanket statement is off-base for two reasons:

- Fat comes in various forms, some of which are actually good for the body and may help clear acne (omega-3 fats in particular), and some of which are potentially harmful and may lead to more acne.

- Research on this topic is not robust enough for anyone to draw any conclusions on the topic.

First, let’s look at the types of fat in food and why a balance is important.

Types of Fat: Omega-3 & Omega-6

Two of the most important fats in food are fatty acids called:

- Omega-3 fatty acids: Wild-caught fish and seafood are rich in omega-3s.

- Omega-6 fatty acids: Oils, nuts, some meats, some vegetables, and some grains are high in omega-6s.

In a typical Western diet, it is far more difficult to consume adequate amounts of omega-3 fatty acids than it is to get the omega-6 fatty acids that your body needs.

When too many omega-6 fatty acids are consumed and too few omega-3 fatty acids, inflammation may result. Since acne is primarily an inflammatory disease, this could hypothetically lead to more acne.

In a 2009 Dermato-Endocrinology article, the author stated:

“Epidemiological studies have shown that increasing the intake of omega-3 fatty acids through a diet rich in fish and seafood lowers rates of acne.”1

More recent scientific reviews have since come to similar conclusions as well.2

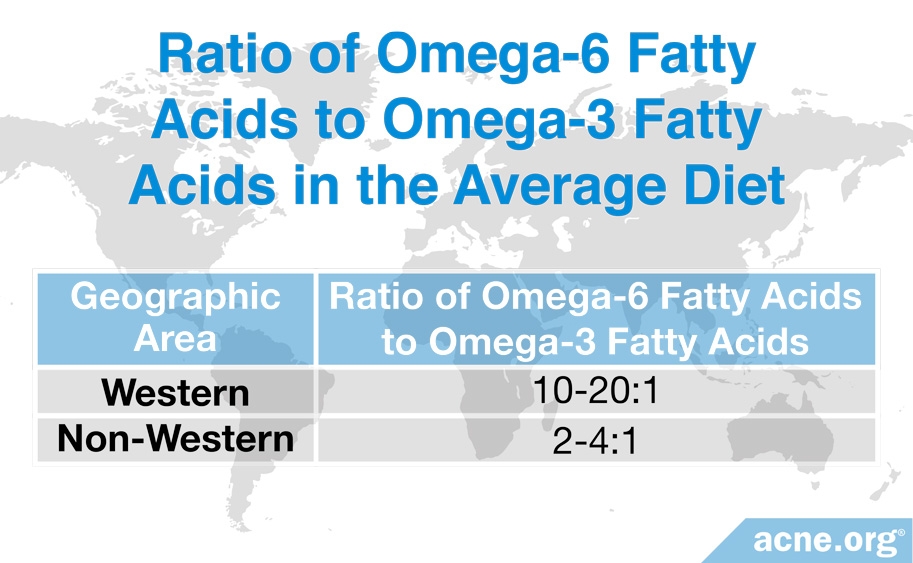

Research suggests that as the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids increases, inflammation also increases.3

A ratio is the relationship between two items. For example:

- A serving of food may contain 2 times as many omega-6 fatty acids as omega-3 fatty acids. This would be a 2:1 (two-to-one) ratio. Inflammation is kept in check.

- A serving of a different food may contain 10 times as many omega-6 fatty acids as omega-3 fatty acids. We would call this a 10:1 (ten-to-one) ratio. Inflammation increases.

As shown in the chart below, the ratio of omega-6 fatty acids to omega-3 fatty acids in the average Western diet is far greater than that in an average non-Western diet.1-4 Moving our diet back toward a non-Western ratio might help reduce bodily inflammation, and thus, acne.

Can Eating Fat Increase Skin Oil Production In the Skin and Lead to More Acne?

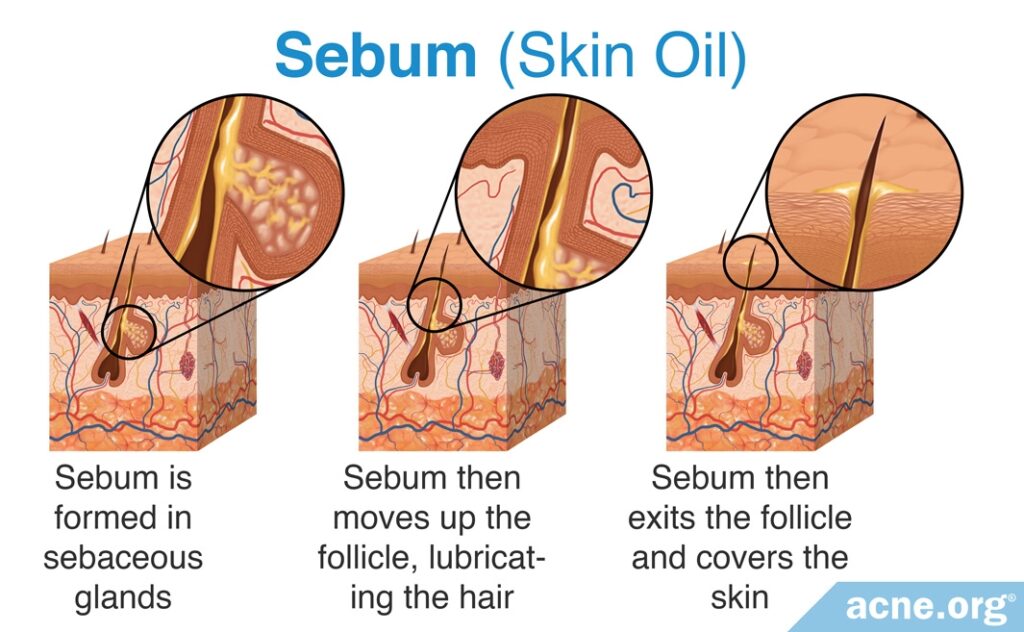

Acne lesions form in any one of the millions of pores in our skin. Attached to the sides of these pores are tiny glands called sebaceous glands, whose job is to produce skin oil. This skin oil, called sebum, is comprised of various fats.

More sebum normally means more acne. So, would eating too much fat cause the body to overproduce sebum? The short answer is we don’t know yet, but when we have a closer look, there are some interesting clues that may give rise to future studies, and hopefully, answers.

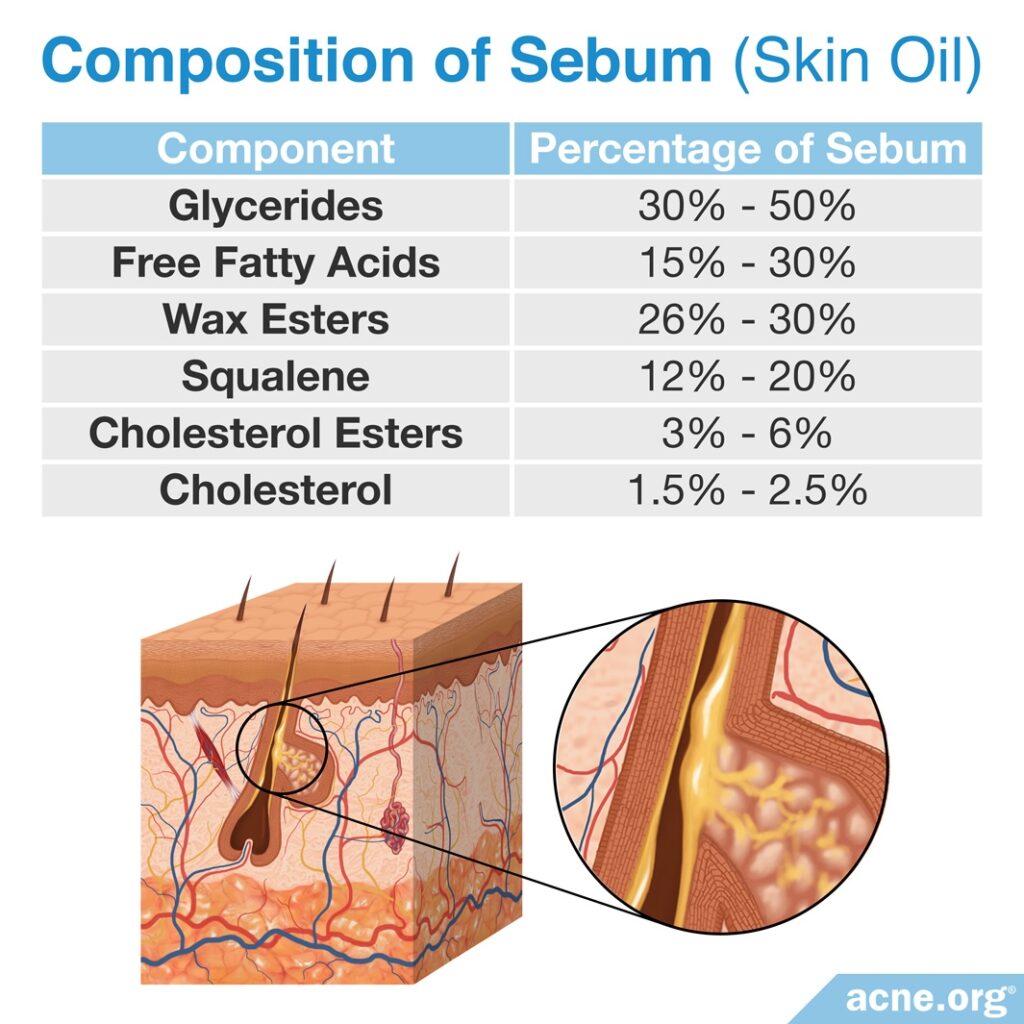

Sebum is made of different types of fat, such as triglycerides, free fatty acids, and cholesterol.

Fatty and oily foods also contain triglycerides, free fatty acids, and cholesterol. One fatty acid in particular, palmitic acid, is of particular interest when we look at how food might affect sebum development. Palmitic acid is present in many foods, including red meat, butter, milk, cheese, and some oils like palm oil, soybean oil, and corn oil.

Palmitic acids – can this fatty acid lead to sebum production?

Sebaceous glands use palmitic acid to form a type of fat that is only found in sebum, called wax esters. This means that the body uses palmitic acid specifically to produce sebum since wax esters are not found elsewhere in the body. This led the researchers to believe that diet probably influences sebum production and, consequently, acne formation.5

However, we must remember that sebum production is a normal process.6 Although scientists know that palmitic acid is used to make wax esters and that wax esters are used to produce sebum, the role of palmitic acid in acne formation remains unknown.

Industrially-produced trans fatty acids, such as those found in fast food, are chemically similar to palmitic acid. It is possible that these fatty acids might also play a role in increasing acne. However, there have been no rigorous studies testing the potential connection between industrially-produced trans fatty acids and acne.7

In short, we simply do not know at this point whether eating more fatty foods, or even fatty foods high in palmitic acid, will increase sebum production. To know the answer to this, researchers will need to perform a long-term randomized controlled trial (RCT), and this has yet to occur.

High-Calorie Content of Fatty Foods

Fat is high in calories. One gram of fat contains 9 calories, while one gram of carbohydrate or protein contains only 4 calories.

High-calorie, fatty fast food options, such as hamburgers, fries, and pizza, are easy to obtain and overeat. One study suggests that, on average, a person visiting a fast food restaurant buys a meal containing 827 calories. That one meal makes up almost half of the normal daily calorie intake – 2000 calories for an average adult.

Since fatty foods tend to be high in calories, we need to consider whether the high-calorie content of fatty food contributes to acne rather than the fat in the food itself.8

How increased calories might lead to more acne

The number of calories in the diet directly affects the levels of certain substances in the body, such as:

- Glucose

- Insulin

- Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1)9,10

Here’s how it goes:

Eating high-calorie foods can bring about high glucose levels in the blood, often referred to as a blood sugar spike. When this occurs, the body produces more insulin and IGF-1 to bring glucose levels back to normal.

And here’s why it’s a concern:

High levels of insulin and IGF-1 have been linked to increased sebum production. And as we mentioned, more sebum normally means more acne.

In other words, since increased sebum production contributes to acne, high-calorie fatty foods might contribute to acne formation through indirectly increasing insulin and IGF-1.11

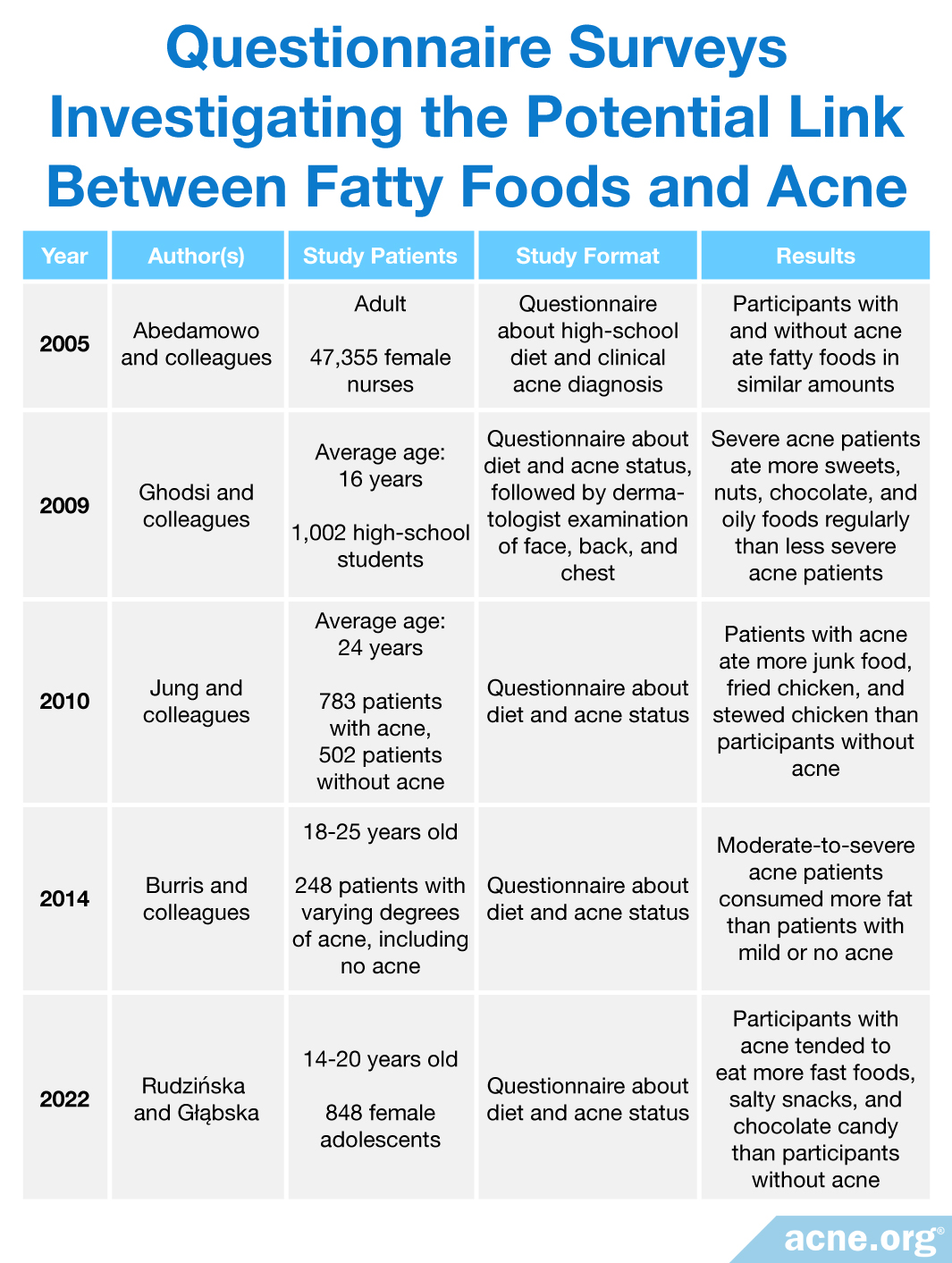

Surveys Investigating the Potential Link Between Fatty Foods and Acne

Researchers have conducted questionnaire surveys investigating the potential link between fatty foods and acne. The results of these surveys hint at an association between certain foods, including fatty foods, and acne.

However, unlike randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which can tell researchers if one factor causes another, survey studies only give us a glimpse at a big picture at one point in time. Since surveys are far less reliable than RCTs, we cannot use them to draw a definitive conclusion on fatty food and acne.

Results of the surveys are presented in the chart below.12-16

An Interview-based Study Looking at the Potential Link Between Fatty Foods and Acne

In 2020, researchers conducted another, somewhat more reliable type of study on fatty foods and acne. In this study, the researchers interviewed 106 volunteers about the types and amounts of fatty foods the volunteers consumed. Half of the volunteers had acne as diagnosed by a dermatologist, and the other half did not have acne but were chosen to be as similar as possible in age, gender, and ethnicity to the volunteers with acne. This type of study is called a case-control study, because for each case of acne, there is a similar person without acne in the study whom the researchers can use for comparison.17

Comparing the volunteers with and without acne led the researchers to conclude that people with acne don’t necessarily eat any more fatty foods than people without acne.17

The scientists published their findings in the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology in 2020. They wrote, “acne severity did not increase as fat consumption increased.”17 However, they noted that more research is needed to make definitive conclusions about the role of fatty foods in acne.

Takeaway

Based on the lack of any RCTs, evidence linking fat intake to acne formation is weak.18 In order to determine whether there is a relationship between fatty foods and acne, researchers will need to conduct RCTs.19 In the meantime, you can’t go wrong by trying to incorporate more omega-3 fatty acids and unprocessed foods into your diet, and limiting fast food consumption within reason.

References

- Picardo, M., Ottaviani, M., Camera, E. & Mastrofrancesco, A. Sebaceous gland lipids. Dermatoendocrinol 1, 68 – 71 (2009). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20224686

- Baldwin, H. & Tan, J. Effects of diet on acne and its response to treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol 22, 55-65 (2021). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32748305/

- Spencer, E. H., Ferdowsian, H. R. & Barnard, N. D. Diet and acne: a review of the evidence. Int J Dermatol 48, 339 – 347 (2009). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19335417

- Wall, R., Ross, R. P., Fitzgerald, G. F. & Stanton, C. Fatty acids from fish: the anti-inflammatory potential of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids. Nutr Rev 68, 280 – 289 (2010). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20500789

- Pappas, A., Anthonavage, M. & Gordon, J. S. Metabolic fate and selective utilization of major fatty acids in human sebaceous gland. J Invest Dermatol 118, 164 – 171 (2002). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11851890

- Melnik, B. C. Western diet-induced imbalances of FoxO1 and mTORC1 signalling promote the sebofollicular inflammasomopathy acne vulgaris. Exp Dermatol 25, 103 – 104 (2016). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26567085

- Melnik, B.C. Linking diet to acne metabolomics, inflammation, and comedogenesis: an update. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 8, 371-388 (2015). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26203267/

- Dumanovsky, T., Nonas, C. A., Huang, C. Y., Silver, L. D. & Bassett, M. T. What people buy from fast-food restaurants: caloric content and menu item selection, New York City 2007. Obesity (Silver Spring) 17, 1369 – 1374 (2009). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19343015

- Pasiakos, S. M., Caruso, C. M., Kellogg, M. D., Kramer, F. M. & Lieberman, H. R. Appetite and endocrine regulators of energy balance after 2 days of energy restriction: insulin, leptin, ghrelin, and DHEA-S. Obesity (Silver Spring) 19, 1124 – 1130 (2011). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21212768

- Henning, P. C. et al. Effects of acute caloric restriction compared to caloric balance on the temporal response of the IGF-I system. Metabolism 62, 179 – 187 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22906764

- Rasmussen, J. E. Diet and acne. Int J Dermatol 16, 488 – 492 (1977). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/142748

- Adebamowo, C. A. et al. High school dietary dairy intake and teenage acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 52, 207 – 214 (2005). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15692464

- Ghodsi, S. Z., Orawa, H. & Zouboulis, C. C. Prevalence, severity, and severity risk factors of acne in high school pupils: a community-based study. J Invest Dermatol 129, 2136 – 2141 (2009). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19282841

- Jung, J. Y. et al. The influence of dietary patterns on acne vulgaris in Koreans. Eur J Dermatol 20, 768 – 772 (2010). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20822969

- Burris, J., Rietkerk, W. & Woolf, K. Relationships of self-reported dietary factors and perceived acne severity in a cohort of New York young adults. J Acad Nutr Diet 114, 384 – 392 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24412232

- Rudzińska, J. & Głąbska, D. Influence of selected food product groups consumption frequency on acne-related quality of life in a national sample of Polish female adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19, 11670 (2022). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36141942/

- Akpinar Kara, Y. & Ozdemir, D. Evaluation of food consumption in patients with acne vulgaris and its relationship with acne severity. J Cosmet Dermatol 19, 2109-2113 (2020). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31840382/

- Davidovici, B. B. & Wolf, R. The role of diet in acne: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol 28, 12 – 16 (2010). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20082944

- Burris, J., Rietkerk, W. & Woolf, K. Acne: the role of medical nutrition therapy. J Acad Nutr Diet 113, 416 – 430 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23438493

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products