Contact Dermatitis Is A Skin Condition Caused by Irritants or Allergens that Usually Results in a Rash

The Essential Info

Contact dermatitis is a common skin disorder that occurs when an irritant or allergen comes into contact with the skin. The skin develops a red or pink rash that may be accompanied by a variety of other symptoms, including:

- Dryness

- Pain

- Itching

- Stinging

- Burning

- Swelling

- Blisters

- Oozing

Common examples of contact dermatitis:

- Nickel jewelry causing a rash on the skin

- Poison Ivy/Oak

- Diaper rash

While contact dermatitis appears on the surface of the skin, it is not acne.

Treatment: Mild-to-moderate cases of contact dermatitis do not require treatment. Most rashes subside within 2-4 weeks, and mild cases can fade in a matter of days. However, over-the-counter or home remedies can help reduce symptoms and quicken recovery, including:

- 1% hydrocortisone cream

- Calamine lotion

- Moisturizers

- Oatmeal compresses

If discomfort is serious or you do not notice improvement after three weeks of home care, make an appointment with your doctor, who may prescribe a topical or oral corticosteroid.

The Science

- Symptoms of Contact Dermatitis

- Causes of Contact Dermatitis

- How Contact Dermatitis Develops

- Diagnosis

- Prevention

- Treatment

- Contact Dermatitis and Acne

Contact dermatitis is a skin condition that develops after skin comes in contact with a substance that is an irritant or an allergen. The skin reacts with a red/pink rash, and depending on the type of contact dermatitis, the rash may also come with dryness, pain, itching, stinging, burning, swelling, blisters, and/or oozing. Most people experience contact dermatitis at least once in a lifetime. Even infants experience a form of contact dermatitis called diaper rash.

Symptoms of Contact Dermatitis

Contact dermatitis develops on areas of skin that have come in direct contact with a trigger irritant or allergen. Symptoms of contact dermatitis usually fade away completely in 2-4 weeks. In mild cases, it can fade away in a matter of a few days. However, when the skin is exposed over and over again to an irritant or allergen, contact dermatitis can become chronic.

Contact dermatitis can be of two types:

- Irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) – caused by an irritant

- Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) – caused by an allergen

Symptoms of Irritant Contact Dermatitis

Irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) develops from substances that irritate the skin on contact, including cosmetics, soaps, unchanged diapers, wet cement, etc.

Clinical features of ICD range from mild to severe, depending on the strength and concentration of an irritant, duration of exposure, and individual sensitivity. In mild cases, symptoms may be limited to subtle dryness and pinkness, whereas in severe cases the rash can be so painful that it distracts from daily activities and disturbs sleep.

Symptoms typically develop minutes to hours after exposure. Mild irritants, like some soaps and cosmetic products, may elicit no response after a single contact, and symptoms will only develop if a person is exposed to them frequently. In contrast, strong irritants, like battery acid, will trigger contact dermatitis almost instantly.

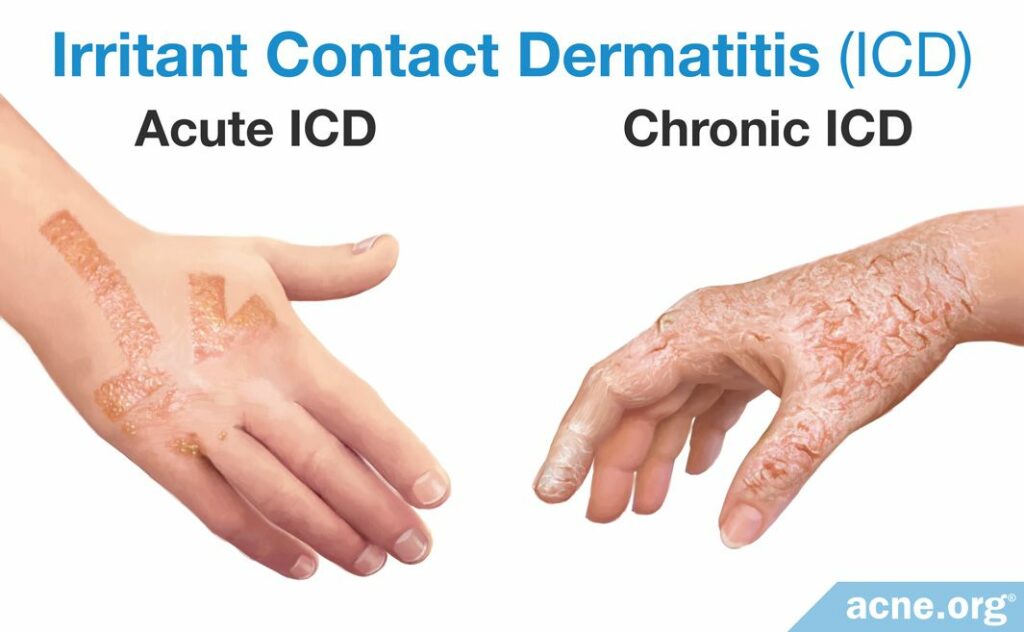

ICD can be:

- Acute – caused by a single exposure to an irritant

- Chronic – caused by repeated exposure to an irritant

Acute ICD: Acute ICD is the result of a single exposure to an irritant. Clinical features of acute ICD include redness/pinkness and dryness of the affected skin and one or a combination of the following symptoms: pain, stinging, burning, swelling, vesicles (blisters <5 mm), bullae (blisters >5 mm), and oozing from blisters. Itching is also possible, but uncommon.

Chronic ICD: Chronic ICD usually develops from acute ICD after repeated exposure to mild irritants. Affected skin is red, thick, dry, scaly, and cracks easily and painfully. Representatives of certain professions, like janitors and hairdressers, are more likely to develop chronic ICD.1

Symptoms of Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) develops from substances that contact your skin that trigger an allergic reaction, including jewelry, latex, personal care products, some medications, plants, etc.

Clinical signs and symptoms of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) almost never develop immediately. Usually, it takes a few hours to a few days for the skin to respond. This is in contrast to irritant contact dermatitis that normally develops more quickly, in minutes to hours. If the skin is exposed to a particular allergen for the first time, usually there is no reaction, but after a second re-exposure, even if it is weeks and months later, ACD may occur.2,3

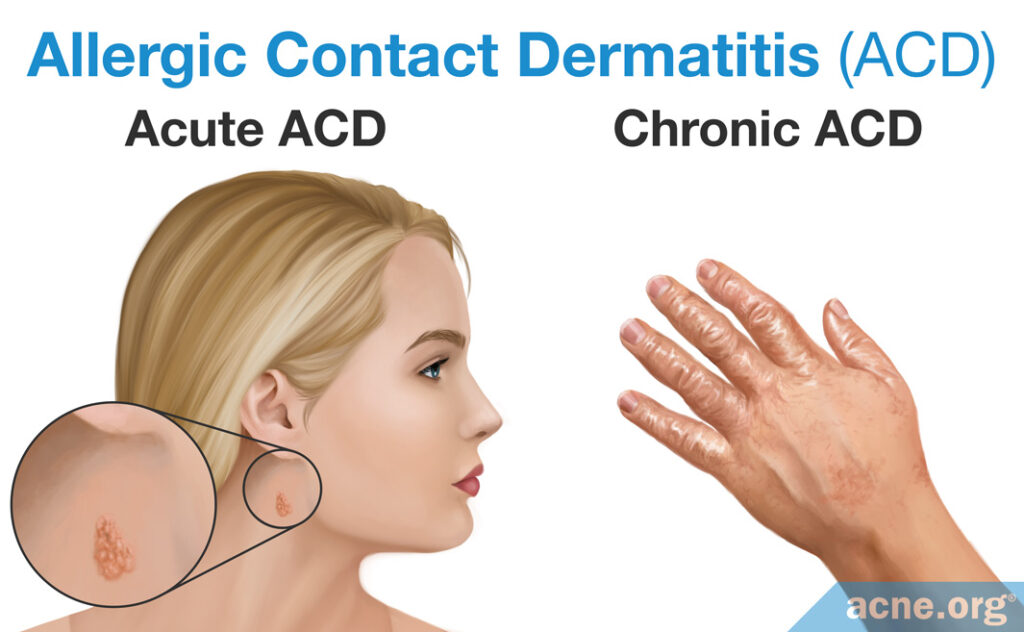

ACD can be:

- Acute – usually caused by re-exposure to an allergen

- Chronic – caused by repeated exposure to an allergen

Acute ACD: Acute ACD normally develops after re-exposure to an allergen. In acute ACD, affected skin is red/pink and almost always itchy. Other typical clinical features may include one or a combination of the following: swelling, dryness, hives (round itchy welts), burning, stinging, vesicles (blisters <5 mm), bullae (blisters >5 mm), and oozing.2

Chronic ACD: Chronic ACD typically develops from acute ACD after repeated (many times) exposure to an allergen. Itch becomes persistent. The skin is red, dry, swollen, flaky, scaly, and cracks easily and painfully.2

A severe reaction to an allergen: Anaphylactic Shock

Anaphylactic shock is a life-threatening, exaggerated, very strong response of the body to an allergen. While it is not contact dermatitis, anaphylactic shock can develop from an allergen coming into contact with the skin.

As discussed, allergens usually do not evoke a reaction immediately, and instead take a few hours to a few days. However, a minority of people develop severe symptoms right away. This kind of intense allergic reaction is known as anaphylactic shock or anaphylaxis.3

Anaphylactic shock presents with one or a combination of the following:

- Difficulty in breathing due to swelling in the throat

- Swelling of the face and/or eyes

- Confusion

If you notice any of these symptoms, call 911 for medical help immediately. If you have an epinephrine autoinjector, use it as soon as you notice these symptoms, but you still need to see a doctor after that.

Causes of Contact Dermatitis

The causes of contact dermatitis depend on whether it is irritant contact dermatitis, which is caused by an irritant, or allergic contact dermatitis, which is caused by an allergen.

Causes of Irritant Contact Dermatitis

When the skin is exposed to an irritant, irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) develops. Irritants destroy skin cells, causing irritation. Unlike allergens, irritants do not cause an allergy.

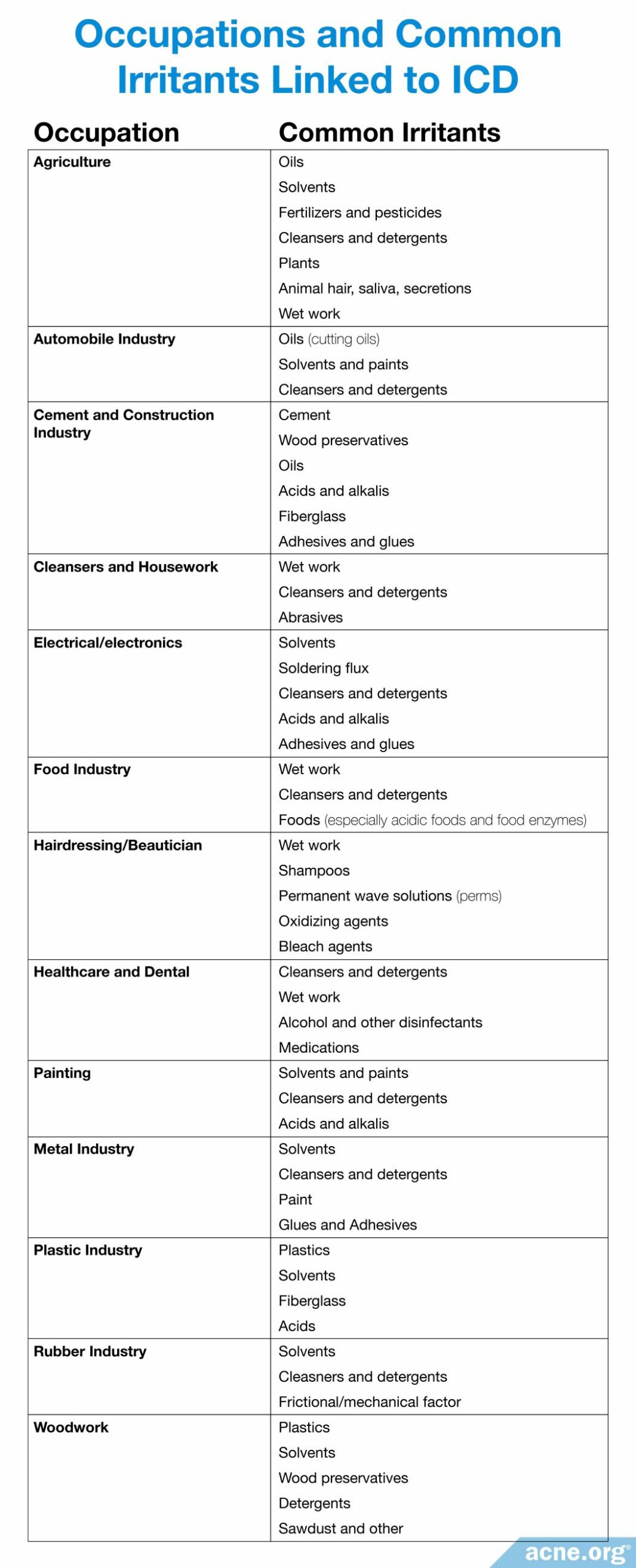

ICD represents about 80% of all types of dermatitis that people get because of profession-related factors.1 The list of occupational fields at risk and the most common irritants encountered in each are presented in the table below.

Causes of Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Substances that trigger allergy on contact with the skin cause allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). Usually, ACD develops only on the areas of the skin that have come in direct contact with an allergen. However, consumed substances that entered your body with food, medication, or flavoring can trigger ACD as well.4 This means you can get ACD from contact with something you happened to eat at some point in the past. For instance, you can get ACD from touching a mango if you ate a mango before and if you are allergic to it. If you eat a mango–an allergy develops, and then if you touch a mango–ACD develops.

Common allergens include, but are not limited to:

- Nickel (in jewelry, eyeglass frames, buckles, etc.)

- Medications (topical antibiotics such as bacitracin and Neosporin®, hydrocortisone cream, oral antihistamines)

- Personal care products (deodorants, body gels, hair dyes, cosmetics, nail polishes)

- Plants (poison ivy; some, like mango, trigger ACD on contact with the skin if you ate them before)

- Airborne substances (ragweed pollen, spray insecticides)

- Formaldehyde (in preservatives, clothing, disinfectants)

- Products that cause a reaction when you’re in the sun, such as some sunscreens and oral medications; this means you put something on that is not going to give you a reaction itself, but then the sun activates the ACD.

How Contact Dermatitis Develops

Irritant Contact Dermatitis

How ICD develops is not fully understood, but we know that multiple pathways are involved. The epidermis is the external layer of the skin that shields us from the outer environment, and irritation of this external layer by a physical irritant like sawdust or a chemical irritant like soap is likely the initiating event. Irritated skin cells release biologically active substances called cytokines that launch inflammation. Simply put, irritation of the skin launches inflammation, and inflammation shows up on the skin with redness, pain, swelling and other symptoms of ICD.1

Allergic Contact Dermatitis

When a certain allergen meets the skin for the first time, usually no symptoms develop. On the cellular and molecular level, though, the immune system carefully examines the allergen and develops a highly specialized weapon in the form of a specialized type of white blood cell to attack it the next time it touches the skin, even if re-exposure happens weeks or months later. Upon re-exposure, even if it occurs months later, the skin fires the white blood cell weapon at the allergen, and inflammation develops as a result.5 Inflammation lies at the base of most symptoms of ACD. You typically notice symptoms 2-3 days after re-exposure. However, some strong allergens, like poison ivy, can elicit a response after the first exposure.4

Diagnosis

Physicians normally diagnose contact dermatitis through carefully examining the rash and asking you questions to determine the cause.3 If the cause remains obscure, your dermatologist may administer a patch test. A patch test looks only for allergens, so it will not reveal the cause if your contact dermatitis resulted from contact with an irritant.

What Is a Patch Test?

Adhesive patches with small amounts of different allergens on them are applied to your back. The patches remain on your skin for 2-3 days, after which the doctor checks if any of the patches produced a skin reaction. If a patch with a certain allergen triggered a reaction, it is likely that this allergen is the cause of your contact dermatitis.

Prevention

Identification of the substance that caused the contact dermatitis and avoidance of that substance are the core elements of success in fighting contact dermatitis.1-3,6 If avoiding a trigger substance is not possible, consult your doctor for advice. For instance, if you are allergic to latex, but you need to use latex gloves at work, you may benefit from using gloves of alternative material or wearing cotton gloves underneath the latex gloves to shield your skin from the latex. If you work with metal and your contact dermatitis is caused by regular exposure to metal particles, a barrier cream, a moisturizer, or an emollient may help. Moisturizers and emollients help by normalizing the water balance of the skin, which is irritated and dry in contact dermatitis.

A 2010 Cochrane review of four clinical trials conducted in occupational settings concluded that the use of moisturizers and barrier creams by print and dye industry workers, hairdressers, and metal workers is effective in preventing hand ICD in these occupations.1

Treatment

Treatment is almost identical for irritant and allergic contact dermatitis. However, treatment is usually not necessary.

Over-the-counter medications and home remedies like 1% hydrocortisone cream, moisturizers, calamine lotion, aluminum acetate, and oatmeal compresses may help reduce symptoms and facilitate skin recovery.

If your symptoms cause you serious discomfort, a doctor may administer you a prescription corticosteroid, either topical or oral.

Topical Corticosteroids – can help with both mild-to-moderate & severe contact dermatitis

Inflammation is at the core of ICD and ACD, so, in mild-to-moderate cases, a 1% over-the-counter corticosteroid cream may be applied for both. Topical corticosteroid cream reduces inflammation and stops the release of pro-inflammatory molecules from skin cells.1,6 In other words, the cream extinguishes the inflammatory reaction.

In more severe cases, a higher percentage corticosteroid medication or a different, more potent topical corticosteroid may be needed, and for that you will have to see a doctor.

Oral Corticosteroids – for severe contact dermatitis

Oral corticosteroids are corticosteroid drugs that you take orally, typically in the pill form. Usually, a topical corticosteroid suffices. Oral corticosteroids are only recommended for:

- Acute and extensive ACD involving the face if topical corticosteroids are ineffective or if quick relief is desired (e.g., for eyelid involvement).

- ACD that involves more than 20 percent of the body surface area.

- ACD that involves less than 20 percent of the body surface area and is disabling or has not responded to treatment with topical corticosteroids.

Usually, oral corticosteroid treatment lasts for about 1 month, but can be shorter or longer depending on your doctor’s orders. It normally begins with 0.5 to 1 mg/kg of an oral corticosteroid called prednisone per day (max. 60 mg daily) for seven days, but other oral corticosteroids aside from prednisone in equivalent dose can be used as well. The dose is halved in the next five to seven days and then gradually discontinued over the following two weeks.

Additional Treatments for Irritant Contact Dermatitis

For ICD, moisturizers have been proven beneficial as an additional treatment. Studies have shown that they are effective in curbing inflammation and restoring a healthy epidermis.1 In other words, the redness and discomfort go away faster, and the skin returns to its normal state.

Additional Treatments for Allergic Contact Dermatitis

In ACD, in addition to corticosteroids, soothing and drying agents such as calamine lotion, aluminum acetate, and oatmeal compresses are helpful.6

Contact Dermatitis and Acne

Contact dermatitis is not acne. The distinctive and different clinical features allow for a relatively easy differentiation between contact dermatitis and acne.

Acne and contact dermatitis are not mutually exclusive, which means you can have both simultaneously. For instance, you can have acne on the face and contact dermatitis on the hand at the same time.

Contact dermatitis might make acne worse

Whether contact dermatitis aggravates acne has not been studied. However, keeping in mind that irritation, especially physical irritation, can aggravate acne, it is reasonable to assume that ICD may worsen acne symptoms.

Research shows that some common ingredients in makeup and skincare products, like preservatives and fragrances, may cause skin irritation and contact dermatitis.7 According to a 2019 article in the journal Dermatologic Clinics, medical journals also identify about 17 new allergens that cause contact dermatitis every year, and a third of these tend to be new ingredients in cosmetics.8

Since some cosmetic ingredients cause skin irritation and contact dermatitis, they may also intensify acne. It’s best to make a habit of reading the labels of cosmetic products and avoid any products containing common irritants like preservatives fragrances. If you know you are allergic to a particular substance, check to make sure it is not among the ingredients.

Some topical acne medications may cause contact dermatitis

In contrast, clinical evidence suggests that some topical acne medications, including bacitracin (topical antibiotic), topical spironolactone, tretinoin, and benzoyl peroxide may sometimes cause contact dermatitis. This contact dermatitis is normally mild-to-moderate and resolves on its own as you continue to use the medication. Though allergic contact dermatitis from topical acne medications is relatively rare, it’s best to perform a patch test before starting to use any new topical treatment just to make sure.9,10

The authors of a study published in Contact Dermatitis (1996) reported that “…3.4% of the patients treated for [acne vulgaris] experienced ACD from their topical [medicine], suggesting that it is not that uncommon.“9

References

- Goldner, R. & Tuchinda, P. Irritant contact dermatitis in adults. UpToDate (2017). at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/irritant-contact-dermatitis-in-adults

- Yiannias, J. Clinical features and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis. UpToDate (2017). at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-features-and-diagnosis-of-allergic-contact-dermatitis

- Contact dermatitis. American Academy of Dermatology (2017). at https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/eczema/contact-dermatitis#symptoms

- Contact dermatitis. Symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic (2017). at https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/contact-dermatitis/symptoms-causes/syc-20352742

- Gaspari, A. Basic mechanisms and pathophysiology of allergic contact dermatitis. UpToDate (2017). at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/basic-mechanisms-and-pathophysiology-of-allergic-contact-dermatitis

- Brod, B. Management of allergic contact dermatitis. UpToDate (2017). at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/management-of-allergic-contact-dermatitis

- Hamilton, T. & de Gannes, G. C. Allergic contact dermatitis to preservatives and fragrances in cosmetics. Skin Therapy Lett. 16, 1-4 (2011). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21611680

- Milam, E. C. & Cohen, D. E. Contact dermatitis: Emerging trends. Dermatol Clin. 37, 21-28 (2019). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30466685

- Balaton, N. et al. Acne and allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis 34, 68-69 (1996). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6222231

- Foti, C., Romita, P., Borghi, A., Angelini, G., Bonamonte, D. & Corazza, M. Contact dermatitis to topical acne drugs: a review of the literature. Dermatol Ther. 28, 323-329 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26302055

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products