Inflamed Acne Refers to Acne That Is Red and Sore, Whereas Non-inflamed Acne Refers to Acne That Is Not

The Essential Info

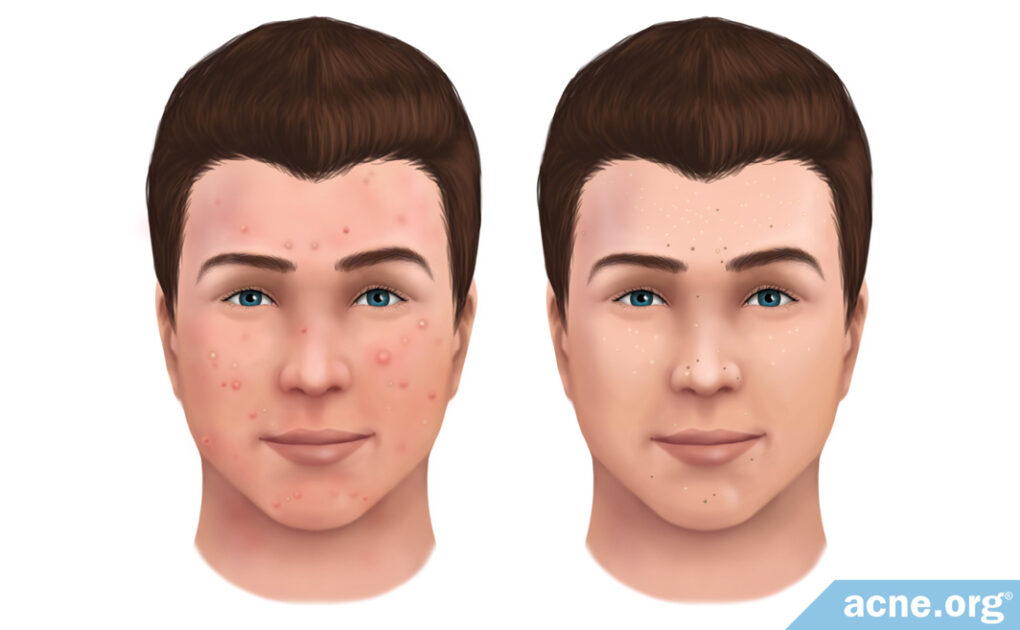

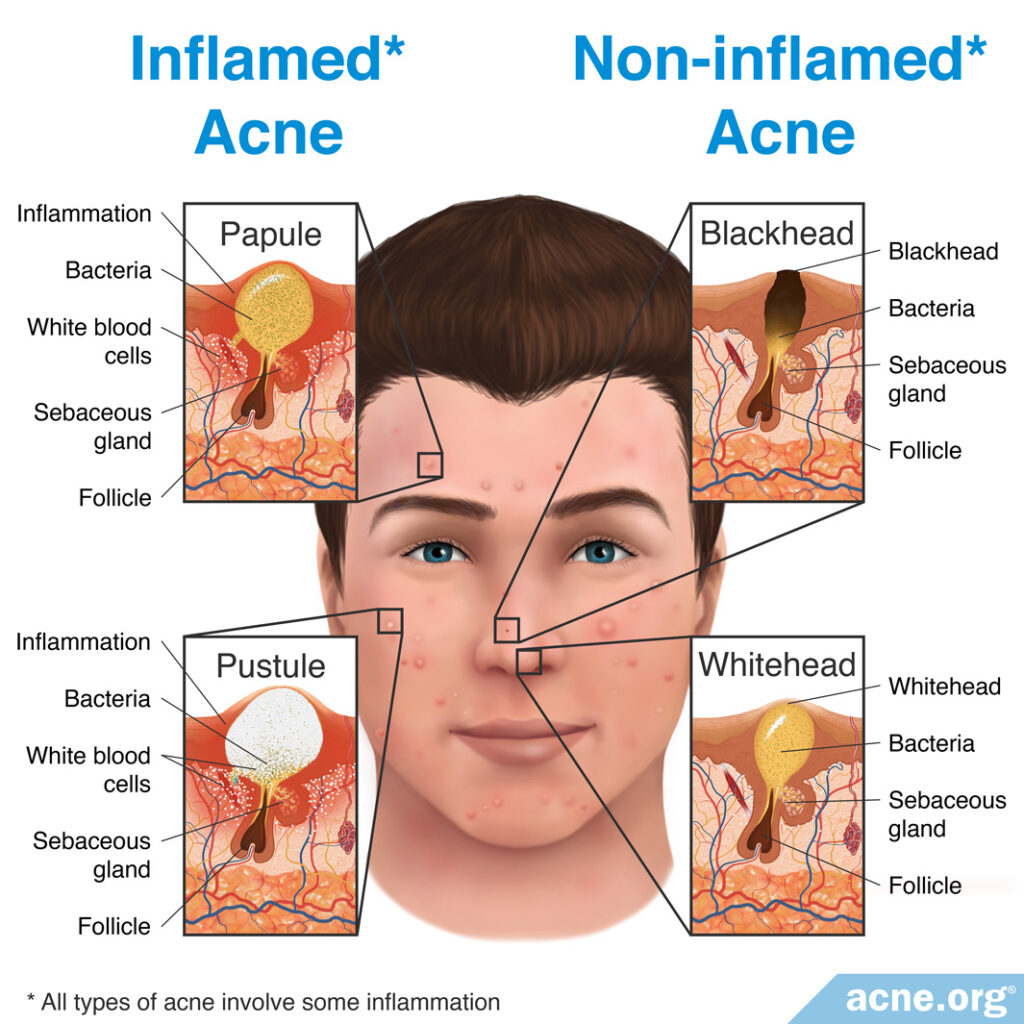

While all acne is on a microscopic level “inflamed,” it is still convenient to use the term non-inflamed acne to refer to whiteheads and blackheads, which are acne lesions that appear as white or black dots on the skin that are not red or sore, and to use the term inflamed acne to refer to red and sore papules and pustules – what people know generally as “zits.”

The Science

- Acne Lesions Begin as Non-Inflamed Lesions and Can Become Inflamed

- The Role of Inflammation in Acne Lesions

Historically, acne was defined as either non-inflamed acne or inflamed acne.

- Non-inflamed: Whiteheads and blackheads were considered to be non-inflamed acne lesions.

- Inflamed: If whiteheads or blackheads ruptured, resulting in a visibly red and swollen acne lesion, doctors and dermatologists referred to them as inflamed acne lesions.

However, in recent years, we have learned more about how acne forms. We now know that inflammation is central to all acne formation, and is in fact the first event in acne formation. In other words, all acne lesions are, essentially, inflammatory.

Still, the dermatology community continues using these terms because it is helpful to differentiate between pimples that are not red and sore vs. pimples that are red and sore.

Acne Lesions Begin as Non-Inflamed Lesions and Can Become Inflamed

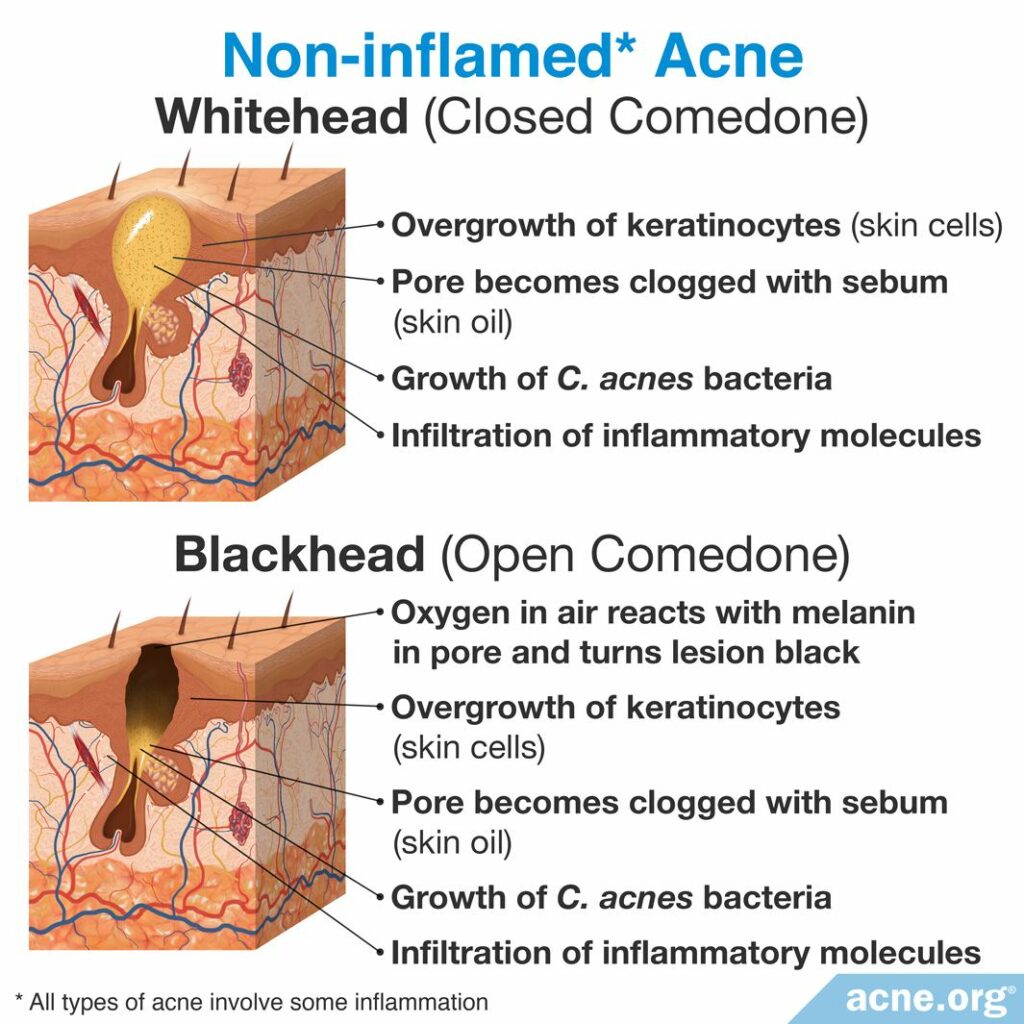

All acne lesions start out as a clogged skin pore, which is actually a tiny hair follicle with skin oil (sebum) glands attached to it.

When a pore first becomes clogged, skin oil, which normally drains to the surface, is now trapped. This makes the pore expand, and become visible. Once it is visible, it is called a comedone, specifically a whitehead or blackhead, which are both non-inflamed lesions, displaying no redness or soreness.1

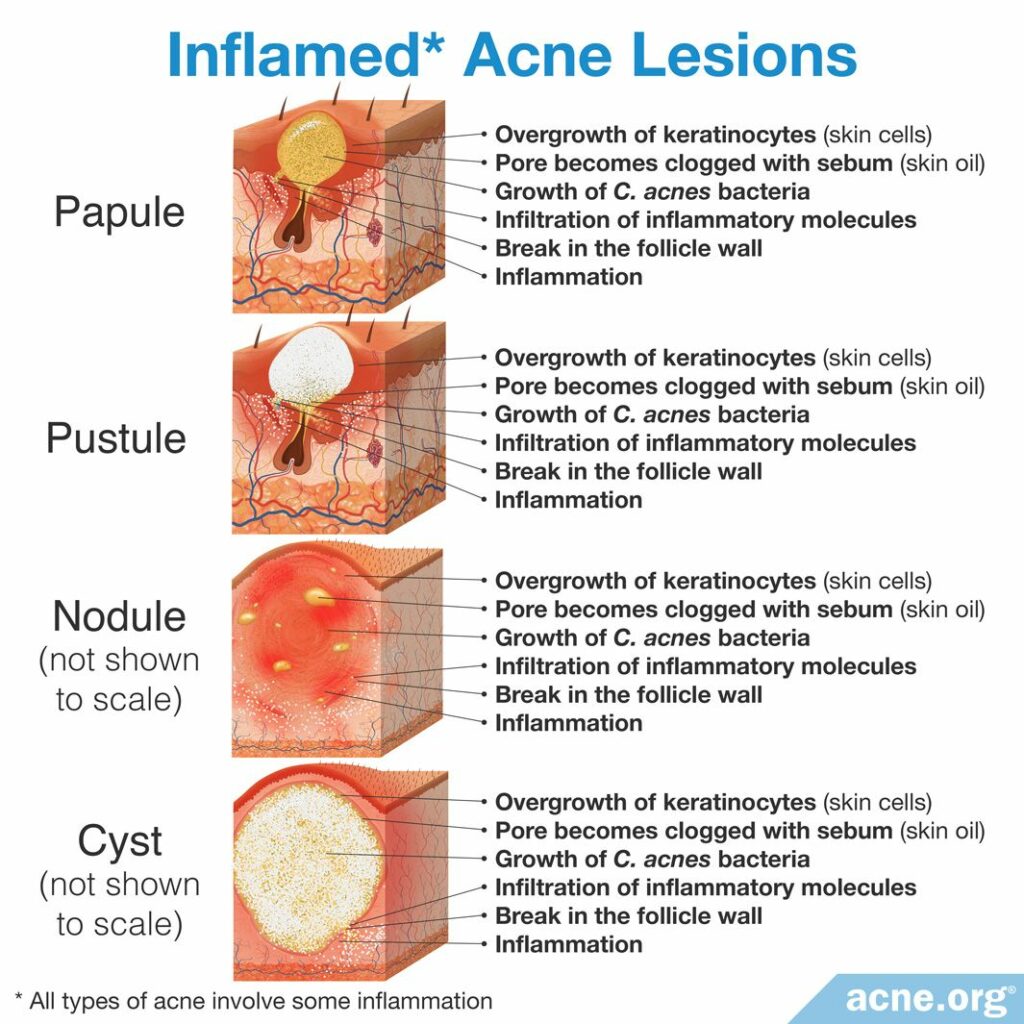

Some whiteheads and blackheads simply heal and go away. However, others swell so much that they burst and become inflamed. When a whitehead or blackhead first bursts, it turns into a red and sore lesion called a papule. A papule often fills with pus, and is then called a pustule.

If a whitehead or blackhead severely bursts deep within the skin, larger, more severe and painful lesions, called nodules or cysts, can also be formed.2

While we can differentiate acne lesions into non-inflamed or inflamed lesions, the process of acne formation is complex, and consists of a “tangled network of four core events.”2 These core events include:

- Inflammation

- An overgrowth of skin cells

- Increases in skin oil (sebum) production

- An overgrowth of acne bacteria

Scientists do not fully understand the exact sequence of these events and how these four factors interact.1 However, the central importance of inflammation in all acne lesions, even so-called “non-inflamed” lesions, is quickly becoming accepted as medical fact. Scientists have found evidence of inflammation already occurring in acne lesions that have only just appeared on the skin in the last few hours. In addition, researchers have observed inflamed lesions popping up “out of nowhere” on healthy-looking skin rather than developing from existing non-inflamed lesions, which again suggests that inflammation may be the first step. A growing body of evidence also shows that anti-inflammatory drugs and herbal remedies with anti-inflammatory properties can help with acne.3-6 Interestingly, anti-inflammatory drugs may even prevent whiteheads and blackheads from forming, giving further credence to the idea that inflammation is behind all types of acne lesions.7-9

Treatment of Non-inflamed Versus Inflamed Acne Lesions

Non-inflamed Lesions: When it comes to whiteheads and blackheads, no treatment is usually needed. Having said that, if you want to get rid of a blackhead quickly for aesthetic reasons, you can undergo professional comedone extraction performed by a doctor, nurse, or esthetician/cosmetician. Keep in mind that blackheads that are extracted in this way tend to fill again in a few weeks.

Inflamed Lesions: Because inflamed lesions are red and sore, they can cause significant discomfort and psychological distress and therefore often require treatment. Many treatments of varying efficacy are available. In particular, The Regimen at Acne.org is often effective at clearing inflamed acne lesions.

Looking More Deeply Into the Role of Inflammation in Acne Lesions

Although there is no visible redness and irritation associated with early comedone formation, research shows that inflammation at the microscopic level is present during all stages of acne formation. In fact, scientists now consider acne to be a chronic inflammatory disease. They classify it as a chronic disease because it lasts for several years, with patterns of relapse and remission, and they regard it as an inflammatory disease because data shows that it is primarily caused by inflammation.1,2

Research has shown that all clogged pores are triggered by inflammatory molecules, especially by a specific inflammatory molecule called interleukin-1 (IL-1). Interleukin-1 increases the body’s production of skin cells, which in turn can clog pores.

Inflammation not only triggers clogged pores, it can also make existing acne worse. Once a comedone bursts, the sebum, skin cells, and bacteria that were in the comedone come into contact with the surrounding skin and trigger the body’s immune system. The body views the contents of the comedone as harmful invaders and tries to fight the invasion by recruiting immune-cells. These cells drive a wave of inflammation that causes the visible redness and pain associated with a papule, pustule, nodule, and/or cyst.2 This secondary wave of inflammation also can contribute to hyperpigmentation (dark/red spots) or scars.10

References

- Williams, H. C., Dellavalle, R. P. & Garner, S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet 379, 361 – 372 (2012). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21880356/

- Tuchayi, S. M. et al. Acne vulgaris. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 1, 15029 (2015). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27189872/

- Tanghetti, E. A. The role of inflammation in the pathology of acne. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 6, 27‐35 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3780801/

- Kim, M., Yin, J., Hwang, I. H. et al. Anti-acne vulgaris effects of pedunculagin from the leaves of Quercus mongolica by anti-inflammatory activity and 5α-reductase inhibition. Molecules 25, E2154 (2020). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32380665/

- Nguyen, A. T. & Kim, K. Y. Inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines in Cutibacterium acnes-induced inflammation in HaCaT cells by using Buddleja davidii aqueous extract. Int. J. Inflam. 2020, 8063289 (2020). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32373312/

- Yang, G., Lee, S. J., Kang, H. C. et al. Repurposing auranofin, an anti-rheumatic gold compound, to treat acne vulgaris by targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome. Biomol. Ther. (Seoul) 28, 437-442. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32319265/

- Leyden, J. Recent advances in the use of adapalene 0.1%/benzoyl peroxide 2.5% to treat patients with moderate to severe acne. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 27 Suppl 1, S4-13 (2016). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26947815/

- Ahluwalia, J., Borok, J., Haddock, E. S., Ahluwalia, R. S., Schwartz, E. W., Hosseini, D., Amini, S. & Eichenfield, L. F. The microbiome in preadolescent acne: Assessment and prospective analysis of the influence of benzoyl peroxide. Pediatr. Dermatol. 36, 200-206 (2019). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30656737/

- Saurat, J. Strategic targets in acne: the comedone switch in question. Dermatology 231, 105 – 111 (2015). https://www.karger.com/Article/Fulltext/382031

- Dreno, B. et al. Understanding innate immunity and inflammation in acne: implications for management. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 29, 3 – 11 (2015). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26059728/

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products