Both Sexes Are about Equally Prone to Acne Scars

The Essential Info

Acne scars are very common. Studies estimate that over 90% of people with acne end up with some degree of acne scarring, although often this scarring is so mild as to be barely noticeable

However, when it comes to gender, acne scars don’t discriminate. Research suggests that both sexes are about equally likely to develop acne scars.

The Science

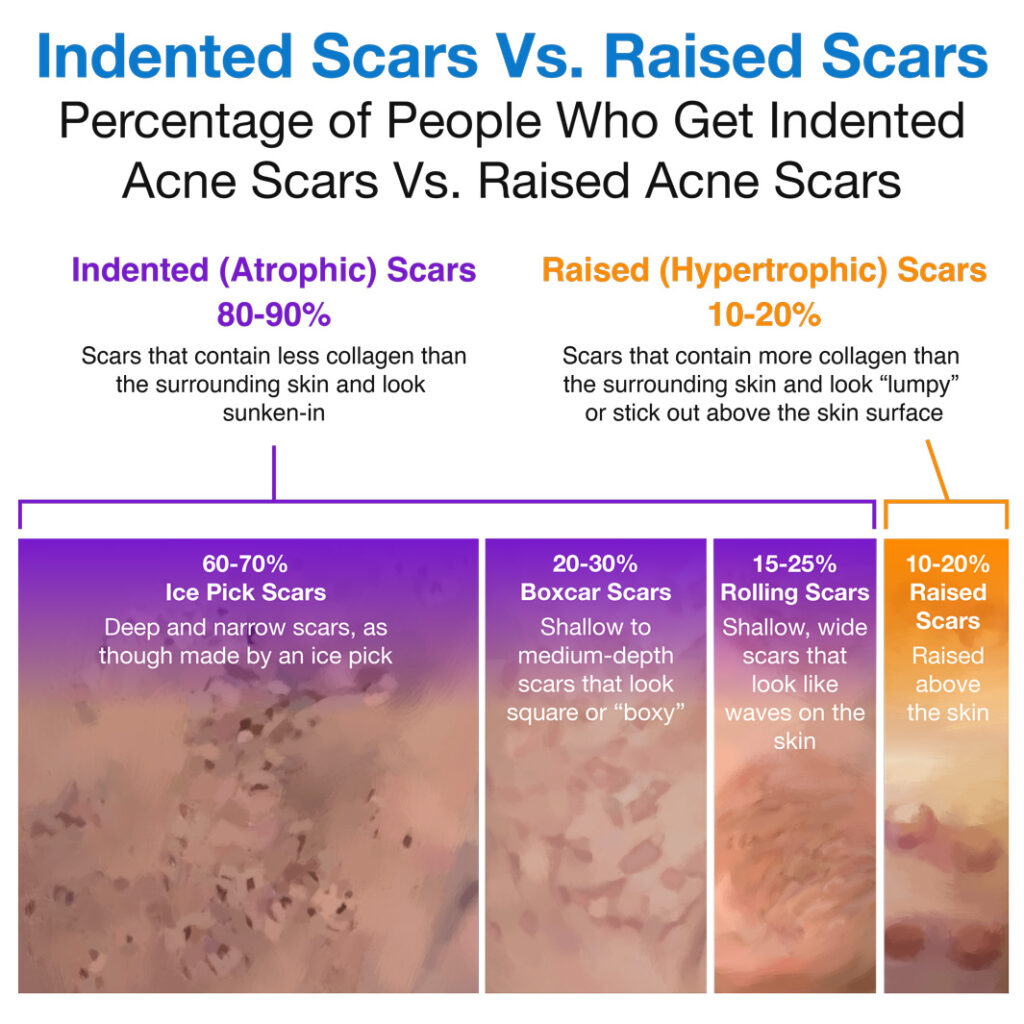

Scarring is a common problem in acne. When an acne lesion heals, the body activates the natural healing process to fill in the lesion with new, smooth skin. Often, however, the body fills the area in with either too little or too much tissue, resulting in either an indented (atrophic) or a raised scar.1,2

Male and female skin has some differences: for example, male skin tends to be thicker and more darkly pigmented, and produces more skin oil than female skin.3,4 A study in mice also found some sex differences in skin healing that might also apply to humans.5 However, in spite of these differences, research so far suggests that male and female skin is about equally prone to acne scarring. Let’s take a closer look.

Studies on How Common Scars Are in Males Vs. Females

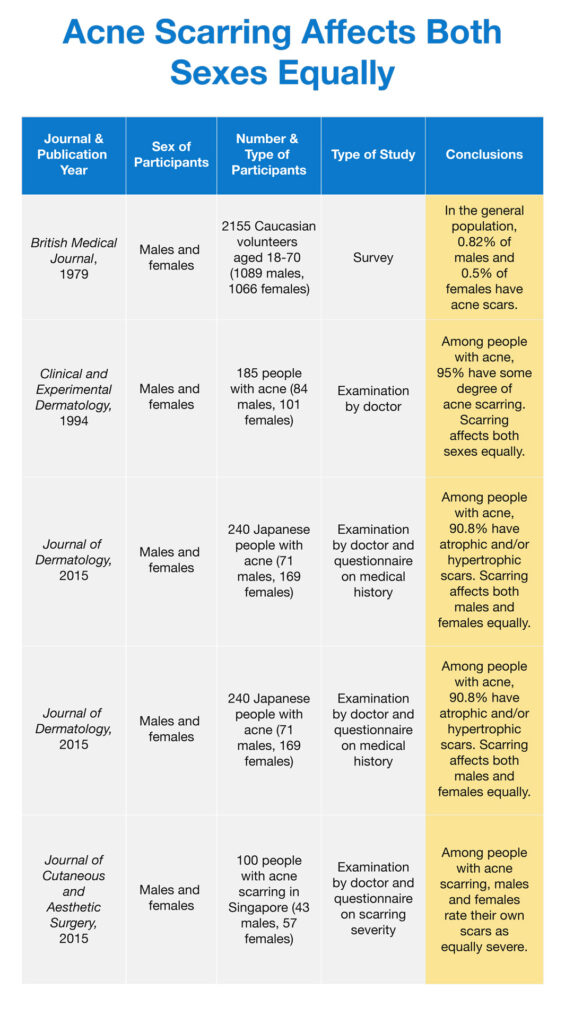

When it comes to scars, most researchers are more concerned with how to treat them than with how common they are in the first place.6 Therefore, only a few studies have directly compared how widespread acne scars are in males versus females. Here’s what they found:

- A study published in 1979 in the British Medical Journal found that among the general population (basically, random people off the street), 0.82% of men and 0.5% of women had acne scars. Most of these scars were indented scars of the icepick type.7

- A study published in 1994 in the journal Clinical and Experimental Dermatology found that up to 95% of people with acne develop scarring, and that scarring occurs in both sexes equally. The study authors wrote, “Facial scarring affects both sexes equally and occurs in up to 95% of cases.”1

- A study published in 2015 in the Journal of Dermatology looked at people with acne in Japan, and found that 93% of the males and 89.9% of the females with acne had acne scars.8

- A study published in 2015 in the Journal of Cutaneous and Aesthetic Surgery looked at people with acne scarring in Singapore. They asked each patient to rate the severity of their own acne scars, and found that males and females rated their scars as equally severe. While this doesn’t tell us common acne scars are in males versus females in Singapore, it does suggest that scarring is similar in severity in both sexes.9

To sum up, research suggests that acne scarring affects both sexes about equally. The table below summarizes all the studies we have discussed.

As more research comes in, we might find that there are subtle differences in scarring between males and females, but so far, it looks like acne scars are equal-opportunity when it comes to gender.1,7-11

A possible exception: Might keloid scars be more common in females?

One recent study brought up the possibility that keloid scars (lumpy-looking raised scars that are wider than the original acne lesion) might be more common in females than in males with acne. In this study, published in Dermatologic Therapy in 2019, researchers looked at patients who came to a plastic surgery clinic in Japan to treat their keloid scars. The researchers found that there were twice as many females as males coming to the clinic with this problem. Therefore, they theorized that female sex hormones might somehow predispose females to developing keloid scars more easily than males.12

However, the fact that more females with keloids came to the clinic doesn’t prove that there were more females than males with keloids. Instead, it is possible that females were more concerned with treating their keloid scars and therefore came to the clinic more readily. For now, all we can say is that females might possibly be more prone to keloids, but we need more research to know for sure.

Treating Your Acne Scars

Acne scars are stubborn and can stick around for a lifetime. According to a 2017 article in the Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology, “Complete resolution of acne scarring is the exception rather than the rule.”2 In other words, while you can make your scars look better, it’s unlikely you’ll be able to fully remove them.

The good news is that there are multiple treatment options to choose from for repairing acne scars. Scar treatments fall into three classes:

- Resurfacing treatments: These procedures create a controlled injury to the skin to trigger the production of new collagen. Examples of resurfacing treatments include laser therapy, chemical peels, and dermabrasion.

- Lifting treatments: These procedures smooth out sunken-in scars by introducing material like fat into deeper layers of the skin. Examples of lifting treatments include filler injections and fat transfer.

- Excisional treatments: These procedures remove the scarred areas of skin completely to trigger the body to produce new skin. An example of excisional treatment is punch excision, a treatment in which a doctor cuts out the scarred skin with a small tool and stitches up the “hole” that’s left behind.1,2,13

Certain treatments work better for specific scar types. Since most people tend to have more than one type of scar, it may be necessary to combine several different treatments for best results.

Research suggests that the more severe the acne, the more severe the scarring tends to be. Therefore, one of the best things you can do to reduce scarring is to treat your acne lesions before they have a chance to progress into more severe forms of acne. Also, never pick at your acne, as this will ramp up inflammation and put you at greater risk of scarring.1,2

References

- Abdel Hay, R., Shalaby, K., Zaher, H., Hafez, V., Chi, C. C., Dimitri, S., Nabhan, A. F. & Layton, A. M. Interventions for acne scars. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, CD011946 (2016). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27038134/

- Connolly, D., Vu, H. L., Mariwalla, K. & Saedi, N. Acne scarring – pathogenesis, evaluation, and treatment options. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 10, 12-23 (2017). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29344322/

- Rahrovan, S., Fanian, F., Mehryan, P., Humbert, P. & Firooz, A. Male versus female skin: What dermatologists and cosmeticians should know. Int J Womens Dermatol. 4, 122-130 (2018). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30175213/

- Giacomoni, P. U., Mammone, T. & Teri, M. Gender-linked differences in human skin. J Dermatol Sci. 55, 144-9 (2009). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19574028/

- Rønø, B., Engelholm, L. H., Lund, L. R. & Hald, A. Gender affects skin wound healing in plasminogen deficient mice. PLoS One. 8, e59942 (2013). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23527289/

- Kubba, R., Bajaj, A.K., Thappa, D.M., Sharma, R., Vedamurthy, M., Dhar, S., Criton, S., Fernandez, R., Kanwar, A. J., Khopkar, U., Kohli, M., Kuriyipe, V.P., Lahiri, K., Madnani, N., Parikh, D., Pujara, S., Rajababu, K.K., Sacchidanand, S., Sharma, V.K. & Thomas, J. Acne scars. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 75, 52-53 (2009). https://ijdvl.com/acne-scars/

- Cunliffe, W. J. & Gould, D. J. Prevalence of facial acne vulgaris in late adolescence and in adults. Br Med J. 1, 1109-1110 (1979). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1598727/?page=1

- Hayashi, N., Miyachi, Y. & Kawashima, M. Prevalence of scars and “mini-scars”, and their impact on quality of life in Japanese patients with acne. J Dermatol. 42, 690-6 (2015). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25916427/

- Chuah, S. Y, & Goh, C. L. The impact of post-acne scars on the quality of life among young adults in Singapore. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 8, 153-158 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4645145/

- Lauermann, F. T., Almeida, H. L. Jr, Duquia, R. P., Souza, P. R. & Breunig, Jde A. Acne scars in 18-year-old male adolescents: a population-based study of prevalence and associated factors. An Bras Dermatol. 91, 291-5 (2016). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27438194/

- Tanghetti, E. A., Kawata, A. K., Daniels, S. R., Yeomans, K., Burk, C. T. & Callender, V. D. Understanding the burden of adult female acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 7, 22-30 (2014). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24578779/

- Noishiki, C., Hayasaka, Y. & Ogawa, R. Sex differences in keloidogenesis: An analysis of 1659 keloid patients in Japan. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 9, 747-754 (2019). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6828900/

- Werschler, W. P., Herdener, R. S., Ross, V. E. & Zimmerman, E. Critical considerations on optimizing topical corticosteroid therapy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 8(8 Suppl), S2-S8 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4570086/

- Fox, L., Csongradi, C., Aucamp, M., du Plessis, J. & Gerber, M. Treatment modalities for acne. Molecules. 21, 1063 (2016). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6273829/