Genetics May Play a Role, but Lifestyle Appears to Be the Answer

The Essential Info

As the decades pass, the incidence of acne increases around the globe. However, isolated hunter-gatherer peoples in developing countries are a startling exception. Adolescents and adults in these communities suffer from acne at a far lower rate than in industrialized areas, and in some tribes, acne is unheard of. Adding complexity to this mystery is the fact that when these isolated people move into industrialized areas, acne starts rearing its head.

Debate about why this is occurring tends to center around diet, but the reasons behind this disparity could be:

Genetics [unlikely]: Do these people just have genetics that protect them from acne? Most likely this is not the case, since when they move into industrialized areas, they tend to start getting acne.

Environment [unlikely]: Could it be that people in hunter-gatherer tribes get more sunlight and fresh air? Or perhaps they are not exposed to acne-causing bacteria? There could be something to the argument that environment has something to do with it, but it is unlikely that this is the whole story.

Lifestyle: [most likely]: Perhaps the natural, whole foods-based diet of these hunter/gatherers protects them from acne? Or perhaps their lower-stress life and connection with nature helps?

Evidence points toward lifestyle as the most likely explanation, but the truth could be that multiple factors all combine to tell the whole story.

The Science

- Prevalence of Acne Worldwide

- The Argument for Genetics

- Is It the Environment?

- Differences in Lifestyle

- The Bottom Line

Prevalence of Acne Worldwide

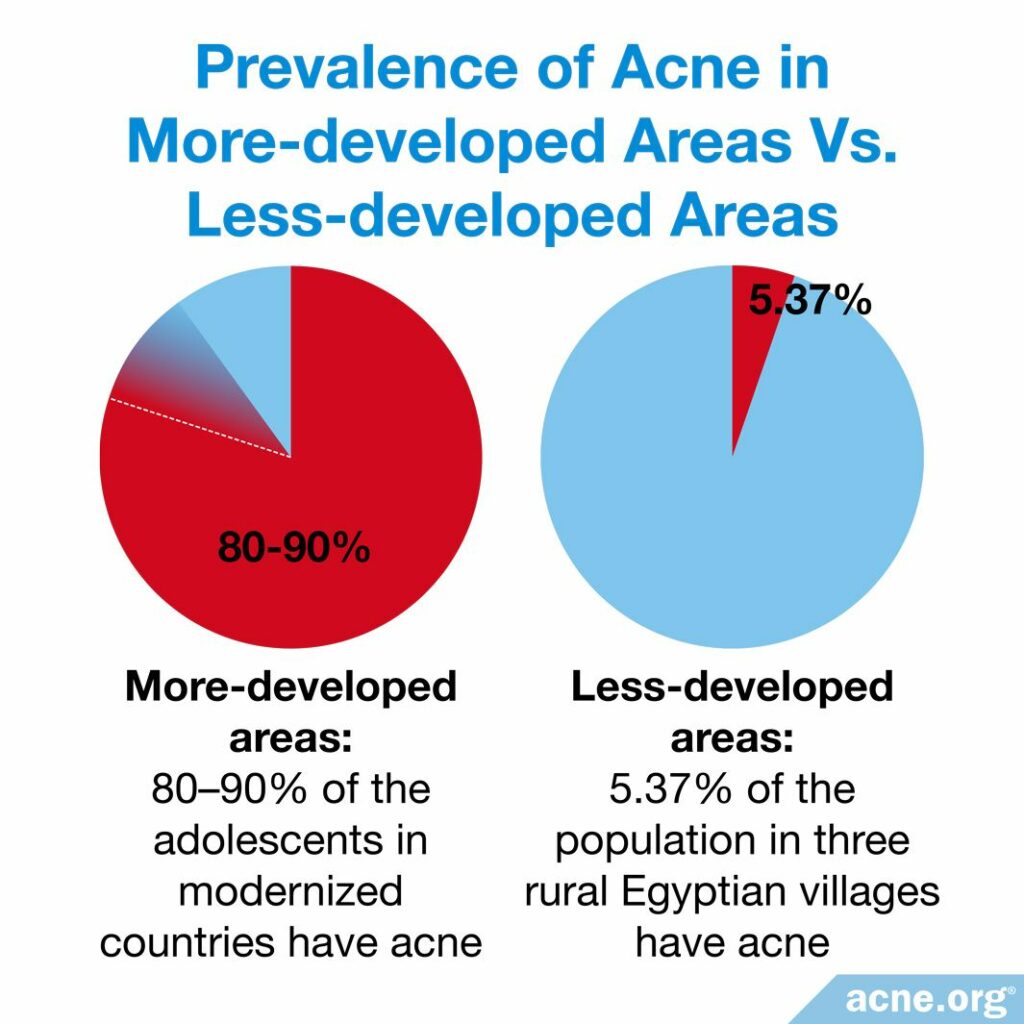

When considered globally, acne affects about 85% of all young adults aged 12 – 25. While the ubiquity of acne among this age group can be explained by the increase in androgens (male sex hormones present in both males and females) during the adolescent years, the reason for the difference in acne incidence rate among developed nations versus developing regions is not readily apparent. Around 80 – 90% of adolescents in modernized countries are afflicted with acne, but this prevalence is much lower in areas that are less developed.1-3

In fact, in a study published in 2011 in the journal, Human Immunology, the authors asserted, “There are even isolated populations where acne is nonexistent, including the inhabitants of the island of Okinawa before World War II, the Bantus in South Africa, the Eskimos, isolated South American Indians, and Pacific Islanders.”2

It is difficult to come by firm numbers of the acne prevalence in poorly developed areas. This is due mainly to underreporting since there is a lack of dermatologists and other healthcare infrastructure. However, there is much evidence to support the overall low prevalence of acne among isolated groups.

For example, in a 2003 study appearing in the International Journal of Dermatology, acne was discovered to affect only 5.37% of the examined population in three rural Egyptian villages.3

Additional evidence for the disparity in acne prevalence between industrialized groups and non-industrialized groups was found among the indigenous people of the Kitavan Islanders of Papa New Guinea and the Aché people in Paraguay. Not a single case of acne was found in either population. Other populations that showed little or no acne include the native people of Okinawa, children in rural Brazil, adolescents in Peru, and adolescents of the Bantu people in South Africa.4 This data reinforces the conclusion that, even accounting for underreporting, acne rates are much lower in indigenous and hunter-gatherer populations when compared to industrialized groups.

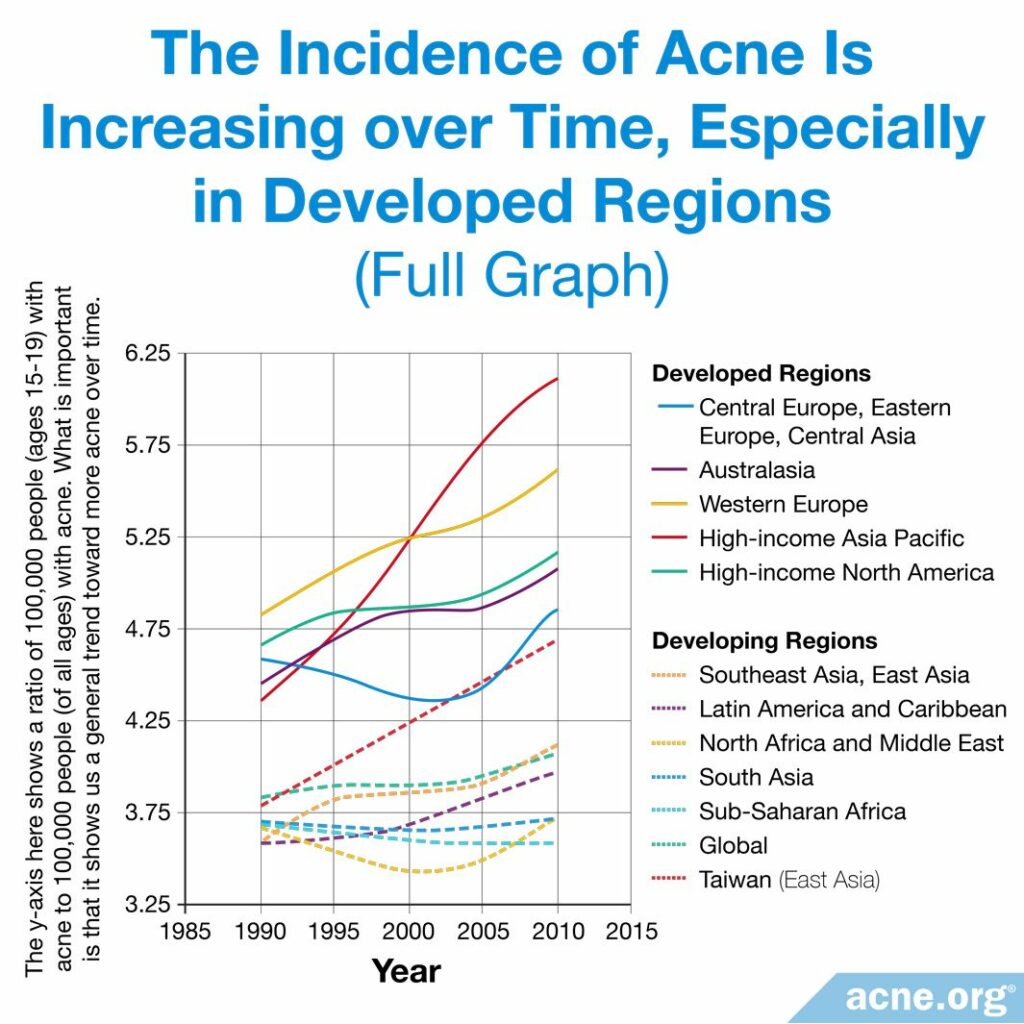

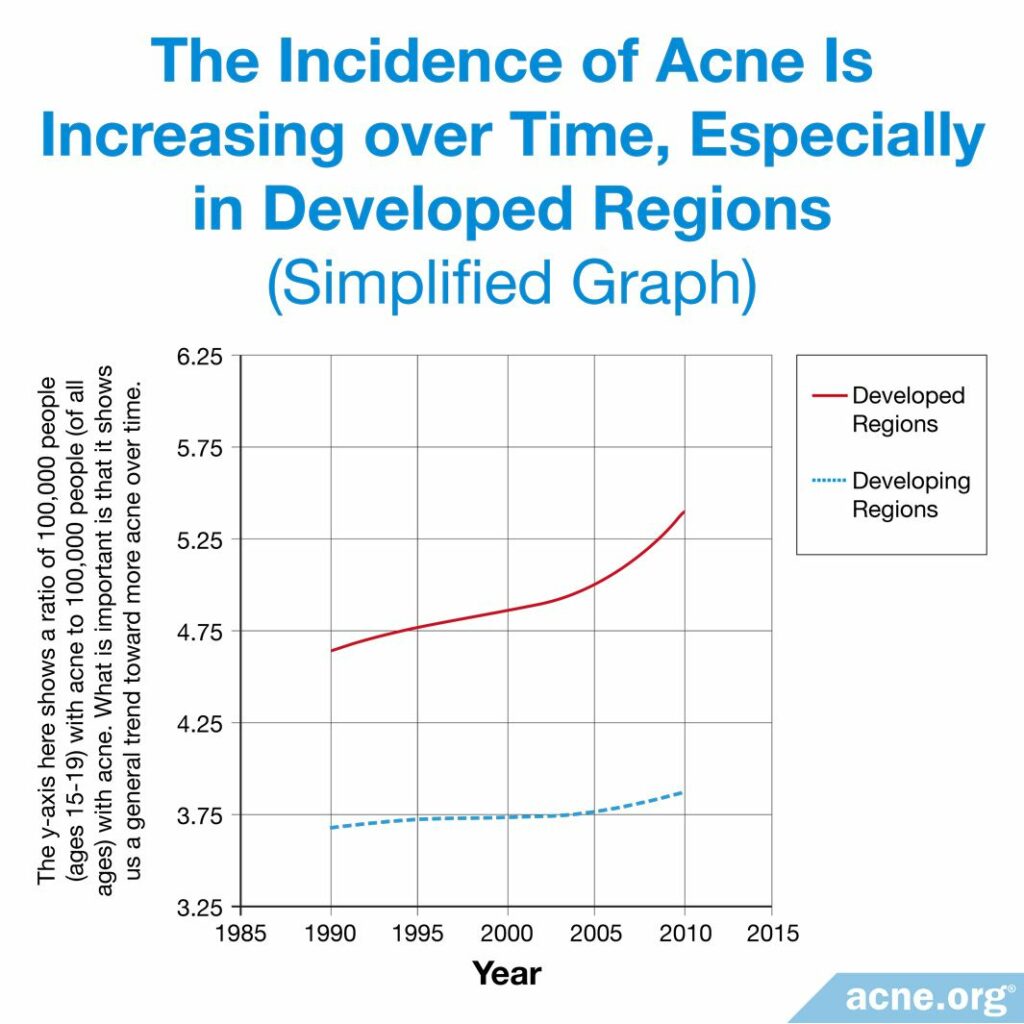

The graphs above illustrate the trend in rates per 100,000 people for acne incidence in a variety of world regions. It is apparent that acne is much more common in developed regions than in developing regions. Developing areas still experience a lower average global incidence of acne, even when accounting for the increase in acne worldwide from 1990 – 2010.1

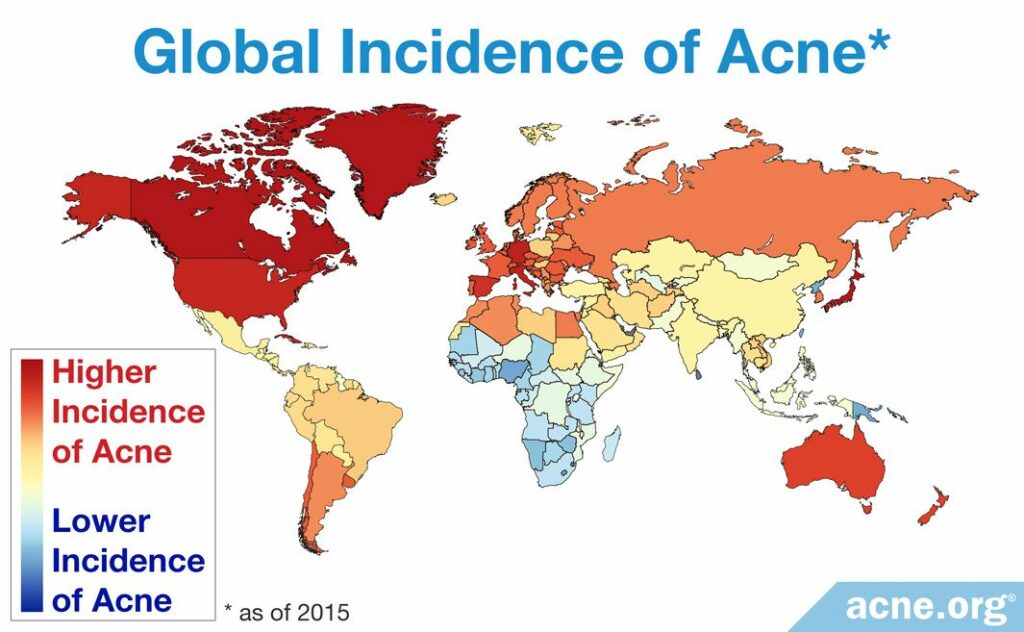

The map above shows the global incidence of acne in 2015. Dark blue indicates a lower incidence, and dark red shows a higher incidence.5

The Argument for Genetics

One theory that accounts for the lack of acne in pre-industrialized people is genetics. In indigenous hunter-gatherers there is little genetic mixing with outside individuals since these groups tend to live in relative isolation. Therefore, hereditary traits in these people are amplified over time and remain undiluted by the introduction of external genes. One tenuous hypothesis is that non-industrialized peoples carry some form of biological protection against acne that is passed down through the generations.

However, the overall argument for genetics as a major cause for differing rates of acne is weak. First, the incidence of acne increased in these populations when these native people transferred to an industrialized location or had Westerners move into their environment. This is seen in examples of Americans arriving in Okinawa and in Zulu people moving from rural to urban locations. In both cases, the rate of acne grew among the indigenous people.4

In addition, it turns out that genetic isolation does not provide protection against acne. On the contrary, there is little opportunity for genetic mixing when a gene pool is isolated, and protective traits may not have a chance to evolve. For example, there may have been no opportunity for these peoples to evolve a protective response to the bacteria often associated with acne, C. acnes, because it was not present in their isolated environment. Yet when they do encounter C. acnes, these indigenous people may experience a reaction because of their lack of protection.2

Since pre-industrialized populations do not retain their apparent immunity to acne when introduced to Westerners or when migrating to urban areas, it is unlikely that genetics plays a significant role in their typical lower acne rates. Rather, the cause of this low acne incidence probably originates from environmental or lifestyle factors.

Is It the Environment?

There are several environmental aspects that could account for the difference in acne rates across the world.

Sunlight: Hunter-gatherers often gain more exposure to sunlight than industrialized peoples because of their lack of indoor facilities. Humans obtain the bulk of their vitamin D through sun exposure, and vitamin D is essential for skin health and healing. Furthermore, as some light therapies are effective acne treatments, it stands to reason that increased sun exposure prevents acne to some extent. The data on this remains inconclusive because of variances in sunlight intensity among several studies. Also, large amounts of sunlight can cause negative effects,7 such as sunburn. Sunburn can bite back with acne in the weeks following exposure as the skin heals.

C. acnes bacteria: Another environmental factor is C. acnes. Doctors have long recognized that C. acnes plays a part in acne formation. However, it is not the root cause. Rather, it enhances only the inflammatory response. Furthermore, individuals with and without acne have tested positive for C. acnes on their skin. It therefore is unlikely that this environmental aspect accounts solely for the rarity of acne among pre-industrialized peoples.7 Even if isolated groups of people have not come into contact with C. acnes, this alone cannot account for their low incidence of acne.

Differences in Lifestyle

There are some major lifestyle differences that may account for the disparity in acne rates between hunter-gatherers and people in developed areas. Chief among these are a diet low in simple sugars and a low-stress lifestyle when compared to industrialized societies.

Diet: Although acne sufferers have been advised for decades to change their diet, there are contradictory conclusions from studies on the subject. Additionally, many studies show a lack of rigor, with small sample numbers and no controls. But even without compelling evidence that diet directly influences acne risk, there is no doubt that eating habits affect general health, and overall health can contribute to the incidence of acne.

For example, a diet high in sugars can lead to overproduction of insulin, which in turn may cause excessive growth of skin cells and proteins that contribute to clogging pores. Too much insulin also may result in oily skin: this is because high levels of insulin may increase male sex hormones. High levels of male sex hormones translates into increased sebum (skin oil) production, and clogged pores and greater amounts of sebum contribute to acne formation.4,7

Stress: The high-stress, modern lifestyle may be the culprit of the higher incidence of acne in developed nations.2 Evidence for this can be seen among current women in developed nations. Women have entered the workforce in great numbers during the last few decades, and accompanying this has been a large increase in acne rates among women. This stands to reason since stress and lack of sleep negatively affect hormone balance and immune functions.6

The Bottom Line

There is an unquestionably lower rate of acne incidence among pre-industrialized, indigenous populations when compared to developed societies. It is unlikely that any single factor fully accounts for this disparity. Possibilities include genetics, environment, and lifestyle or a combination of any of these. While genetics likely is not a contributing factor, environmental and lifestyle factors cannot be discounted. Specifically, a diet low in simple carbohydrates and a relatively stress-free lifestyle seem to account for the rarity of acne in hunter-gatherer peoples, although the argument is not settled.

References

- Lynn, D., Umari, T., Dunnick, C. & Dellavalle, R. The epidemiology of acne vulgaris in late adolescence. Adolesc Health 2016, 13 – 25 (2016). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4769025/

- Szabó, K. & Kemény, L. Studying the genetic predisposing factors in the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris. Hum Immunol 72, 766 – 773 (2011). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21669244

- Abdel-Hafez, K., Abdel-Ayu, M. A. & Hofney, E. R. Prevalence of skin diseases in rural areas of Assiut Governorate, Upper Egypt. Int J Dermatol 42, 887 – 893 (2003). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14636205

- Cordain, L. et al. Acne Vulgaris. Arch Dermatol 138, 1584 – 1590 (2002). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12472346

- Institute for Health Metrics And Evaluation. GBD Compare | IHME Viz Hub. Global Burden of Disease (2015). https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/

- Albuquerque, R. G., Rocha, M. A., Bagatin, E., Tufik, S. & Andersen, M. L. Could adult female acne be associated with modern life? Arch Dematol Res 306, 683 – 688 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24952024

- Bhate, K. & Williams, H. C. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol 168, 474 – 485 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23210645

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products