Non-comedogenic Skin Care Products Claim to Be Less Likely to Cause Acne. However, This Claim Cannot Be Guaranteed.

The Essential Info

“Comedogenic” means that a product is likely to clog skin pores, which can then lead to acne lesions.

“Non-comedogenic” means that a product is not likely to clog pores.

The root word of each term is “comedone,” which is the medical term for a clogged pore.

Natural processes in our skin can lead to clogged pores, but ingredients in cosmetics can sometimes be the culprit as well.

Manufacturers of skin care products may advertise their products as “non-comedogenic” or may choose to simply say “will not clog pores,” but the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not regulate these claims, so there is no guarantee that products labeled as such will not cause acne.

The Science

- “Comedogenic” Explained

- “Non-comedogenic” Explained

- Formulating Non-comedogenic Products

- The Comedogenic Testing Process

- The Bottom Line

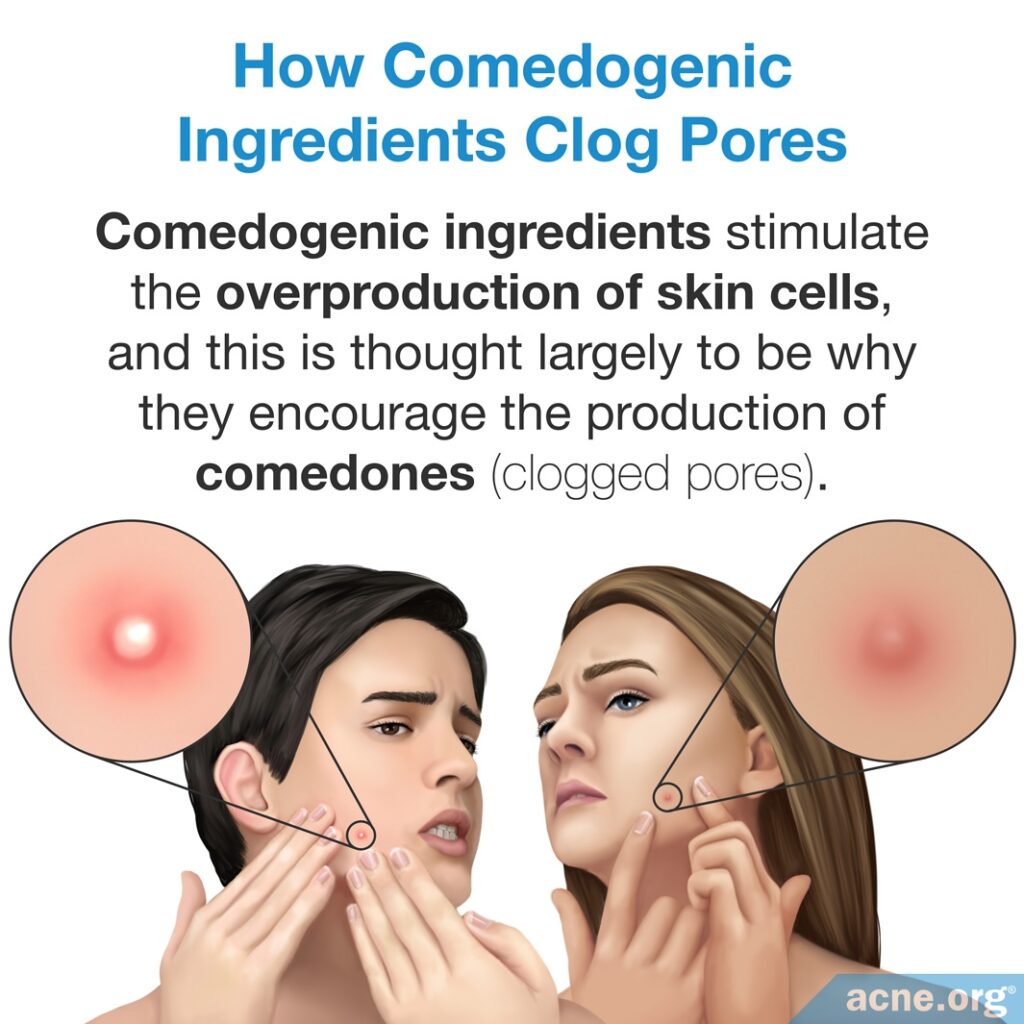

Comedogenic ingredients are ingredients that lead to clogged pores, called “comedones.”

The most likely way that comedogenic ingredients clog pores is by stimulating the overproduction of skin cells inside a skin pore, which leads to a pore blockage and ensuing acne.1-6

“Comedogenic” Explained

The term comedogenic refers to a substance that causes comedones (clogged pores). The term acnegenic is also sometimes used and means the same thing.

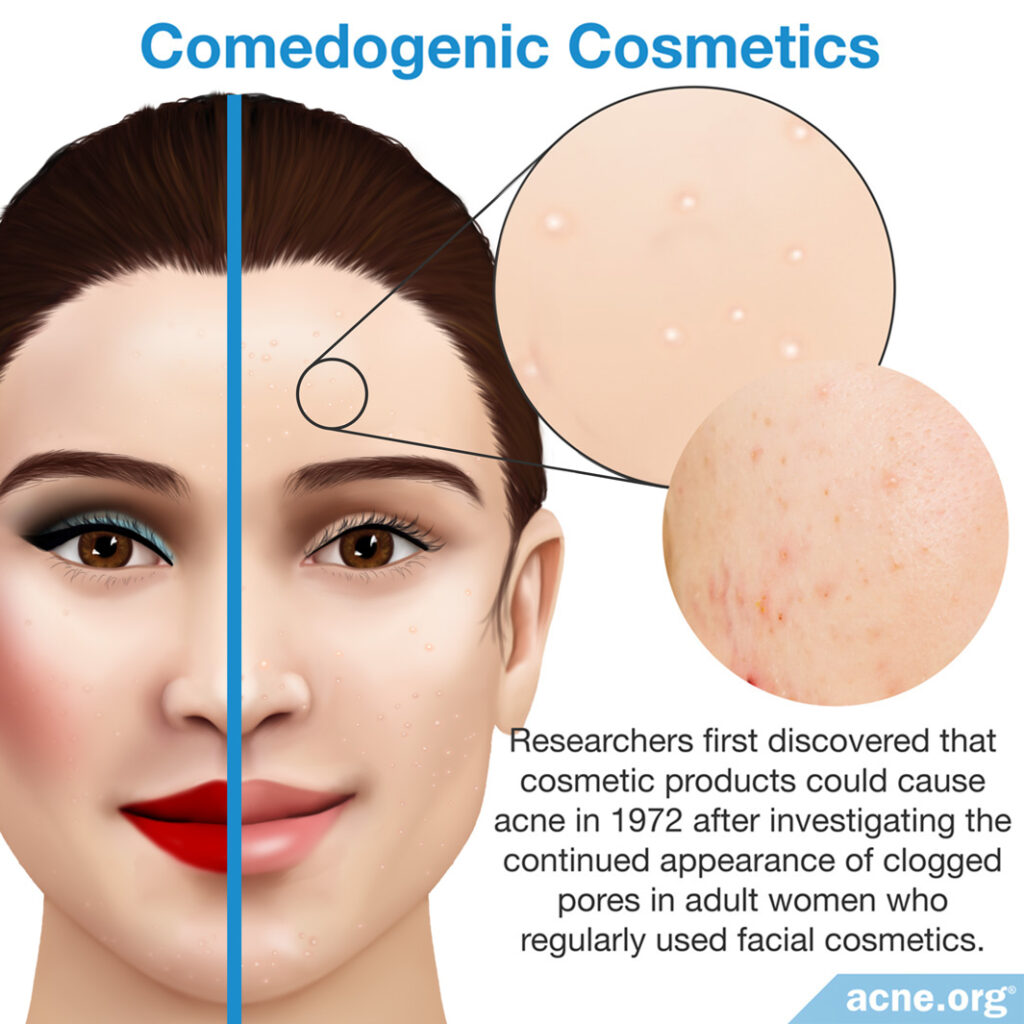

Researchers first discovered that cosmetic products could cause acne in 1972 after investigating the continued appearance of comedones in adult women who regularly used facial cosmetics. The researchers called the condition “acne cosmetica,” and this initial discovery led to much more research regarding exactly which ingredients might be causing clogged pores.5

“Non-comedogenic” Explained

The term non-comedogenic refers to substances that should not cause clogged pores.

The discovery of acne cosmetica prompted manufacturers to develop cosmetic and skin care products that are more likely to be non-comedogenic.3 Today, a host of skin care brands advertise their products as non-comedogenic.

However, people who use products labeled as non-comedogenic should know that the FDA does not regulate this term. This means that although some manufacturers can support their claims with research and product testing, no regulatory agency requires them to do so in order to make comedogenicity claims about their products.

Formulating Non-comedogenic Products

Producing non-comedogenic skin care products and cosmetics is a challenge because most products contain many ingredients, and it is difficult to predict how each of those ingredients will interact with different people’s skin.5

Product formulators try to make educated guesses about how comedogenic an ingredient might be based on its chemistry, such as how big the molecule is.6

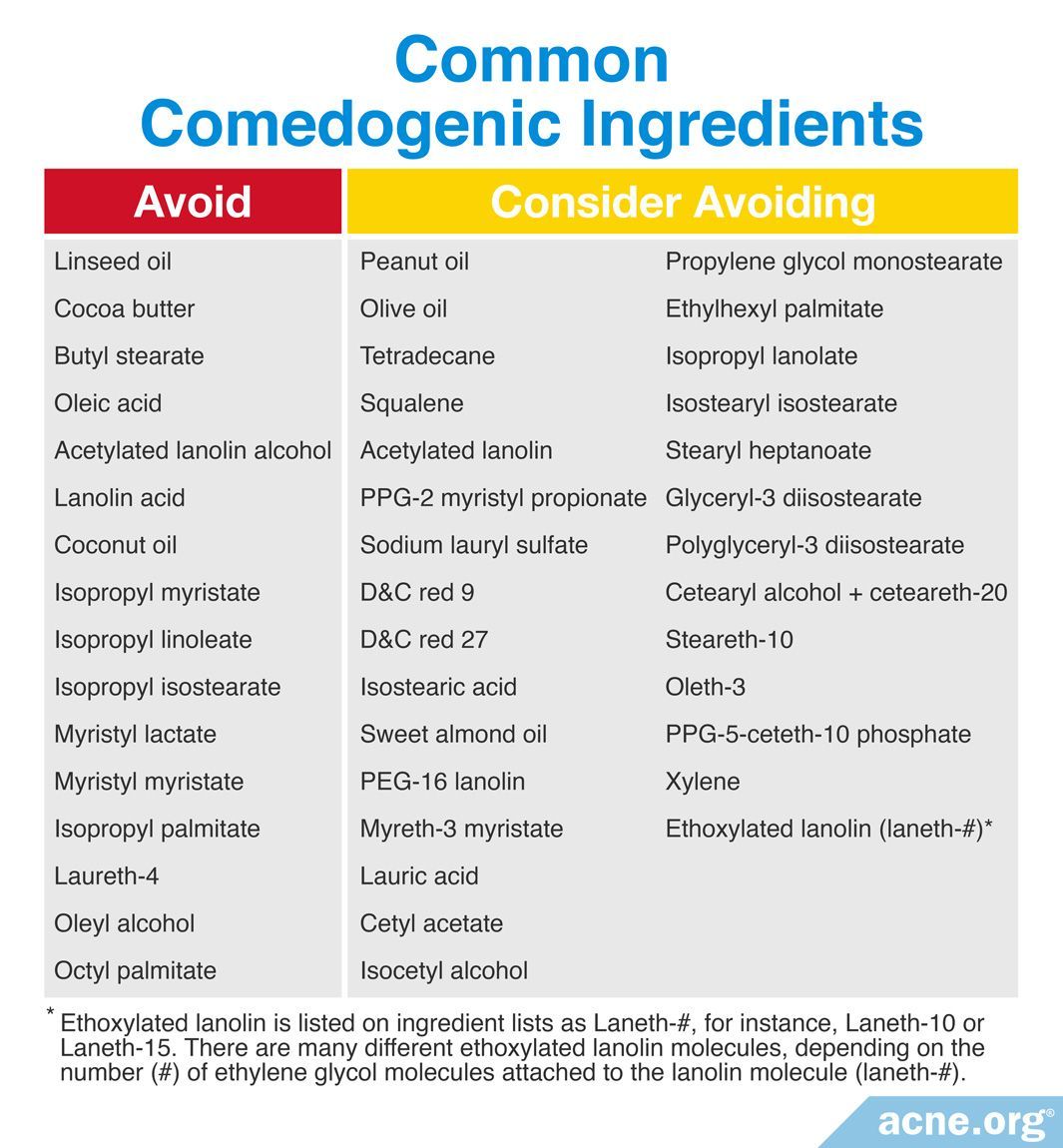

Another tool that product formulators have is to simply avoid using ingredients that have been shown to be comedogenic in laboratory testing. The first list of results for the comedogenic potential of ingredients was published in a 1989 study in the Journal of the Society of Cosmetic Chemists:

“By taking these products apart, testing their ingredients, and putting them back together and retesting them, an extensive ingredient listing has been created. By studying this list, the cosmetic chemist can begin to be selective in developing formulas for less irritating and less comedogenic products.“6

However, even if individual ingredients are classified as non-comedogenic, it is possible that a combination of non-comedogenic ingredients interact and become comedogenic. To avoid this, the American Academy of Dermatology recommended in 1989 that manufacturers test products that contain three or more non-comedogenic ingredients, just to be sure that the combination of ingredients doesn’t end up clogging pores.3

The Comedogenic Testing Process

The rabbit ear test and the human method are the two testing models that are usually used to determine if ingredients are comedogenic.

Rabbit ear test:

The rabbit ear test is the most common way of determining whether ingredients are comedogenic. In this test, a researcher exposes the inner ear of an albino rabbit to an ingredient, for example, an oil at 10% strength, and evaluates how the skin responds after a two-week period.

The major disadvantage of this test is:

- The skin of a rabbit’s ear is much more sensitive than human skin, and sometimes ingredients appear to be more comedogenic in the rabbit than they are in humans.6

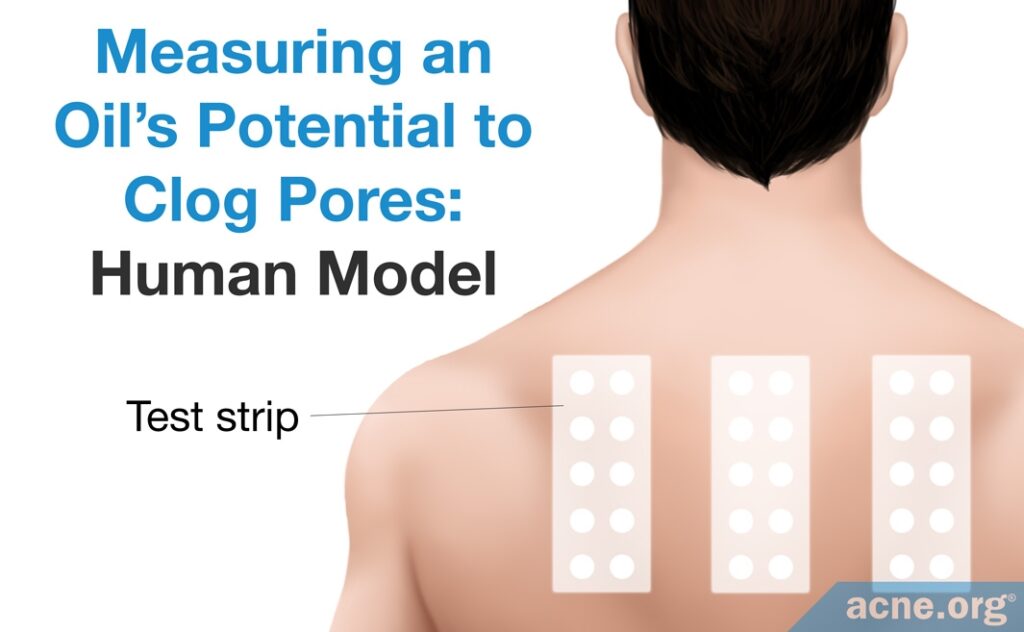

Human method:

Researchers also perform comedogenic testing of product ingredients on human skin, partly due to opposition to animal testing in some countries. In this method, an absorbent patch is saturated with an ingredient and applied to a person’s back, and then evaluated after four weeks. Researchers will often test several ingredients at once in this manner. This technique is used on the back to make the patch less conspicuous.7,8

Comedogenic testing in humans presents a few disadvantages:

- Researchers have not used the human method for as long as the rabbit ear test. While the method of the rabbit ear test has been standardized, the human method has not. Because of this, different researchers will often employ the human method in different ways, leading to inconsistent outcomes.

- It takes more time to obtain results than it does with the rabbit ear test.3

- The skin on the back, where the test is performed, differs from the facial skin, where most skincare products are actually applied.3,7,9 That’s why some researchers have suggested performing human skin testing on the cheek instead.10

As we can see, both the rabbit ear test and the human method come with disadvantages, and therefore, comedogenicity testing is an imperfect science.

The gold standard for comedogenicity testing would be so-called “in-use clinical trials,” which are tests on actual patients who use products as they are meant to be used. However, in-use clinical trials are expensive to run, so companies rarely perform them.7

The fact is, there is no universal industry standard for what a company has to do before it can write “non-comedogenic” on its product labels. Therefore, such labels are often nothing more than a marketing tool.9

The Bottom Line

Since the FDA does not regulate the claim “non-comedogenic” on cosmetic and skin care products, it is difficult to know how much testing the manufacturer actually performed, if any, when they came to this conclusion. Due to this unregulated environment, as well as limitations in product testing procedures, consumers should be aware that some “non-comedogenic” products may still cause clogged pores and breakouts.

The best way to determine if a product might break you out is to look at the ingredient list and avoid using products that contain highly comedogenic ingredients within the first seven (7) ingredients listed on the label.

References

- Williams, H. C., Dellavalle, R. P. & Garner, S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet 379, 361 – 372 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21880356

- Toyoda, M. & Morohashi, M. Pathogenesis of acne. Med. Electron Microsc. 34, 29 – 40 (2001). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11479771

- Draelos, Z. D. & DiNardo, J. C. A re-evaluation of the comedogenicity concept. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 54, 507 – 512 (2006). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16488305

- Mirshahpanah, P. & Maibach, H. I. Models in acnegenesis. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 26, 195 – 202 (2007). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17687685

- Kligman, A. M. & Mills, O. H. Jr. Acne cosmetica. Arch. Dermatol. 106, 843 – 850 (1972). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4264346

- Fulton, J. E. Comedogenicity and irritancy of commonly used ingredients in skin care products. J. Soc. Cosmet. Chem. 40, 321 – 333 (1989). http://www.nononsensecosmethic.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Comedogenicity-and-irritacy-of-commonly-used-ingredients.pdf

- Weiss, C. & Caswell, M. Non-comedogenic and non-acnegenic claim substantiation. J. Cosmet. Sci. 68, 253‐256 (2017). https://library.scconline.org/v068n04/10

- Waranuch, N., Wisutthathum, S., Tuanthai, S., Kittikun, P., Grandmottet, F., Tay, F. & Viyoch, J. Safety assessment on comedogenicity of dermatological products containing d-alpha tocopheryl acetate in Asian subjects: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 23, 100834 (2021). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34471722/

- Xu, S., Kwa, M., Lohman, M. E., Evers-Meltzer, R. & Silverberg, J. I. Consumer preferences, product characteristics, and potentially allergenic ingredients in best-selling moisturizers. JAMA Dermatol. 153, 1099‐1105 (2017). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28877310

- Baek, J. H., Ahn, S. M., Choi, K. M., Jung, M. K., Shin, M. K., Koh, J. S. Analysis of comedone, sebum and porphyrin on the face and body for comedogenicity assay. Skin. Res. Technol. 22, 164-169 (2016). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26094640/

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products