Proper Healing of Acne Lesions Is Important in Order to Avoid the Formation of Scars

The Essential Info

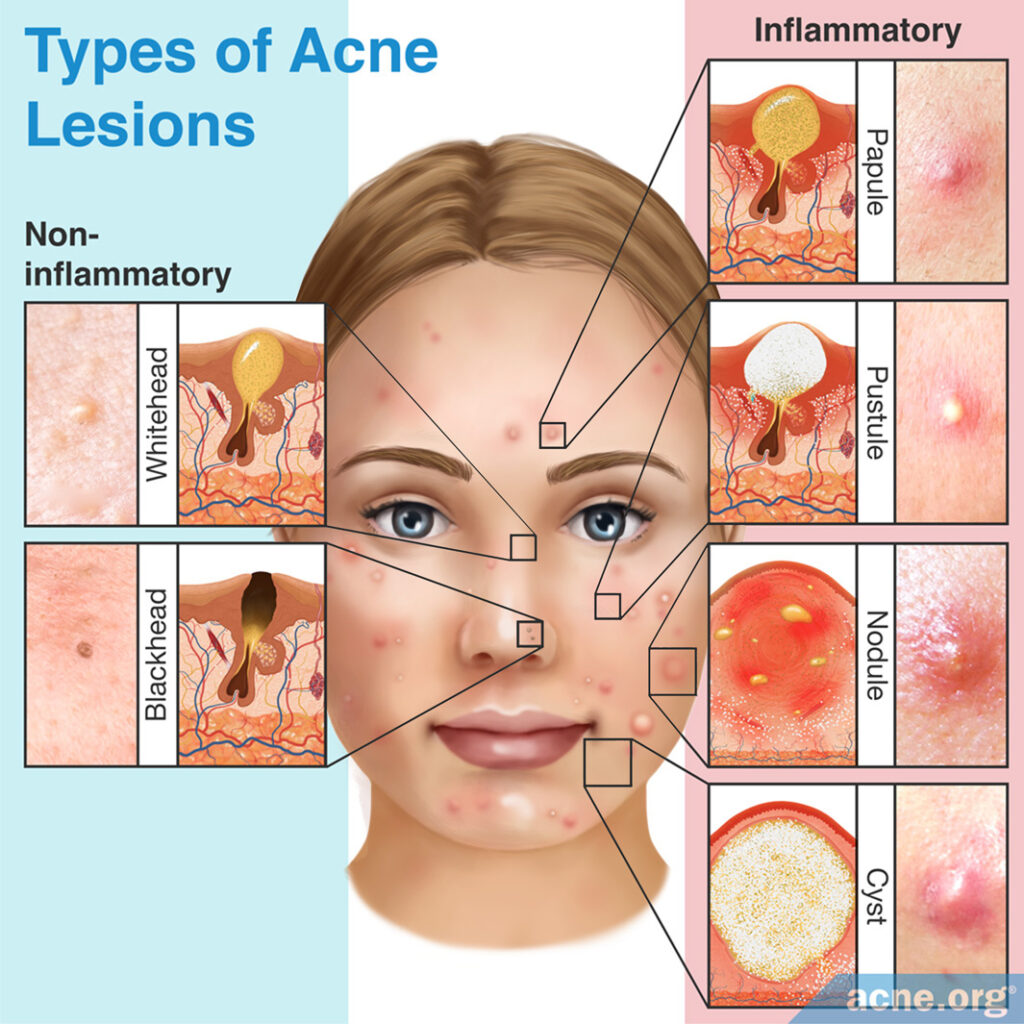

Some lesions, such as whiteheads, heal quickly and usually without scarring. More severe lesions, such as nodules and cysts, take longer to heal and often leave scars.

This article explains the biology behind how acne lesions heal. Regardless of the type of lesion, the fundamental process of healing is the same, involving these three phases:

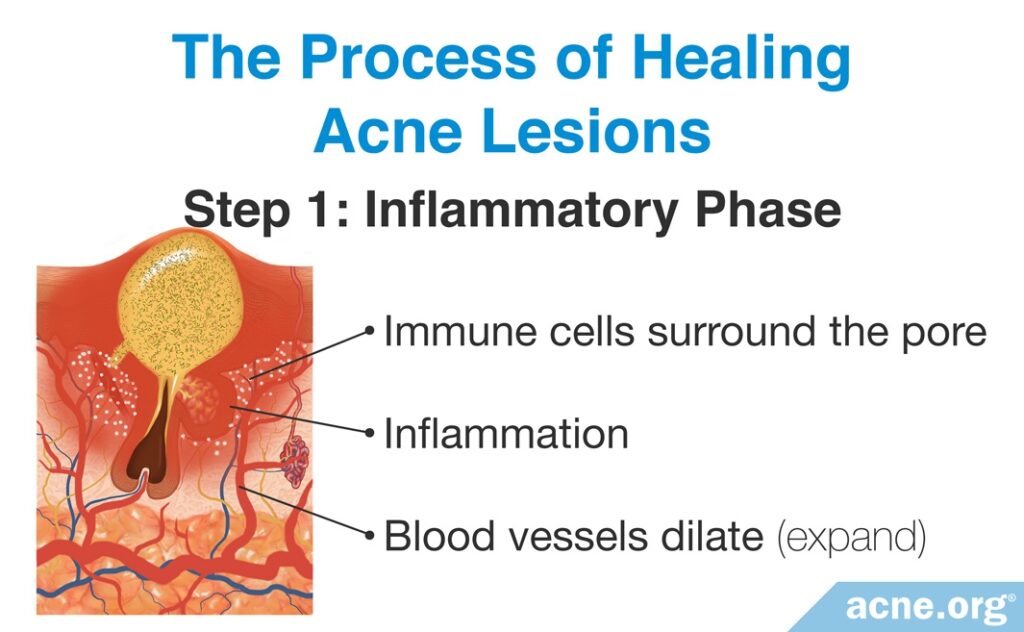

- Inflammatory phase: The body reacts by sending in inflammatory molecules to start the process of healing, and blood vessels dilate.

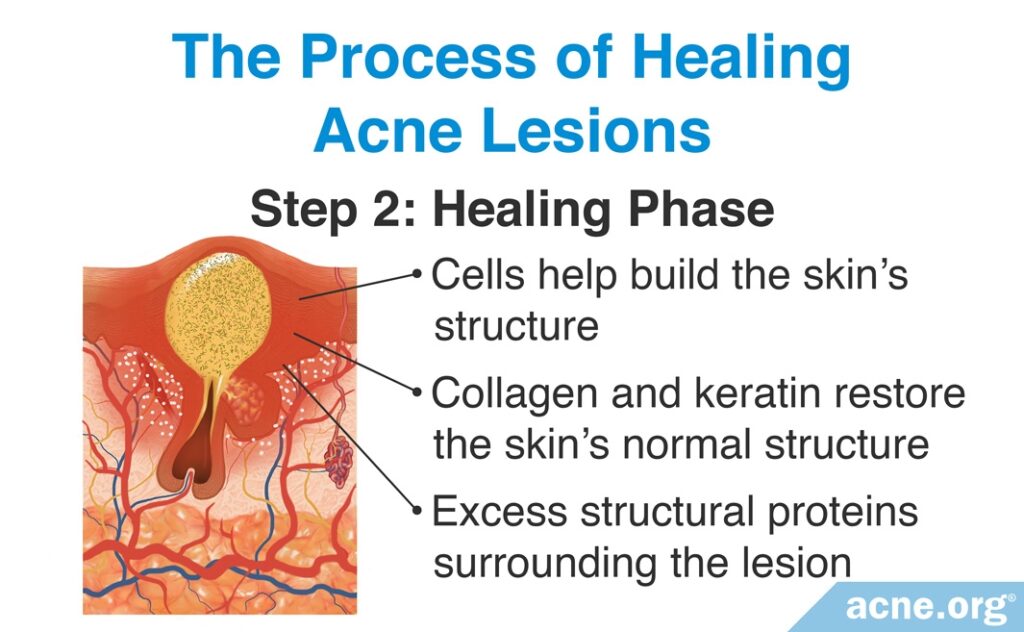

- Healing phase: Skin proteins join in and start rebuilding the skin.

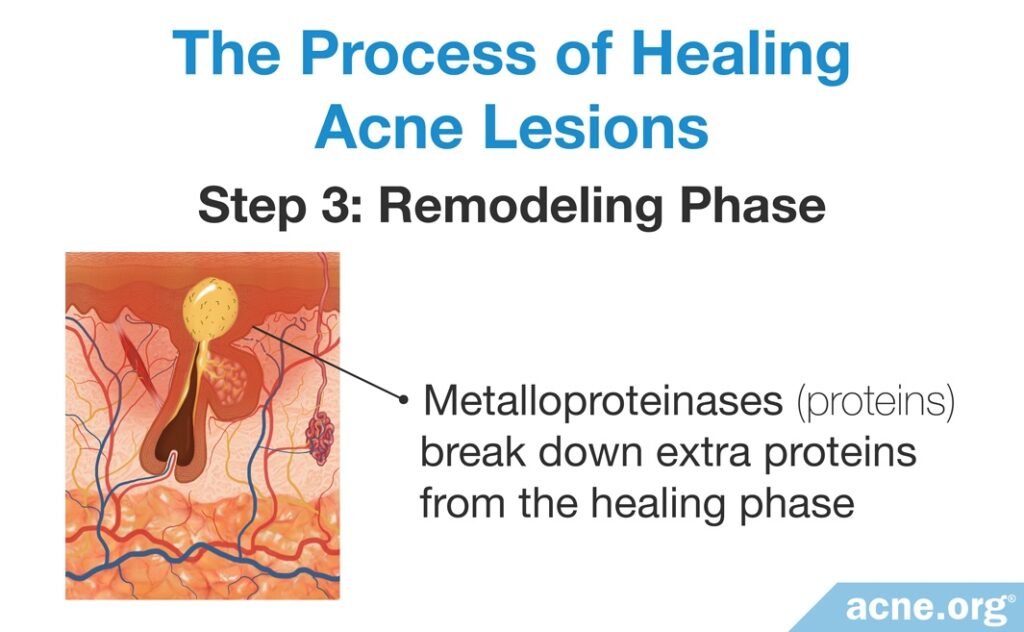

- Remodeling phase: This is a “clean up” phase that tidies up the extra skin proteins from the healing phase and returns the skin to normal.

The Science

Acne is primarily an inflammatory disease. In fact, inflammation is present throughout the entire cycle of an acne lesion, from before a recognizable lesion even forms all the way until the lesion is healed.

According to a 2014 article in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology, “Recent research has confirmed that inflammation is the hallmark of all acne lesions.“1

Different types of lesions have different amounts of inflammation associated with them. The amount of inflammation determines how quickly an acne lesion heals and affects whether the lesion leaves a scar when it heals.

For example, whiteheads and blackheads typically have minimal inflammation and heal within 7-10 days without scarring, while inflammatory nodules and cysts have extensive inflammation and take much longer to heal and can leave severe scars.1-2

The Process of Healing Acne Lesions

Regardless of the type of lesion or amount of inflammation present, the fundamental process of healing acne lesions is the same for all lesions:

- Step 1 (Inflammatory Phase): The first step in healing acne lesions is an inflammatory phase, in which immune cells surround the skin pore and produce inflammatory proteins. These inflammatory proteins cause the surrounding blood vessels to dilate (expand), resulting in the redness that is characteristic of inflammation.

- Step 2 (Healing Phase): The second step is a healing phase, in which a variety of cells become active that help build the skin’s structure. These cells produce structural proteins such as collagen and keratin that help restore the skin’s normal structure. This phase ultimately results in an excess of these proteins surrounding the lesion.

- Step 3 (Remodeling Phase): The final step is a remodeling phase, in which proteins called metalloproteinases break down the extra proteins from the healing phase, so that the lesions heal without any extra skin tissue. We can think of this final step as a “clean-up” phase, in which the metalloproteinases tidy up the mess that was left behind during the healing phase. Depending on the severity of the original lesion, the remodeling phase can last up to several months. The degree of inflammation present in the acne lesion affects what happens during the remodeling phase, and that affects whether or not a scar forms when the lesion heals. Acne lesions with more extensive inflammation leave scars when they heal, while those with less inflammation often heal without scarring.3-5

Acne Scar Formation

Scientists believe that an acne scar forms as a result of two processes:

- Inflammation: As we have seen, the more inflamed an acne lesion is, the higher the chance of scarring after the lesion heals.

- Improper breakdown and/or production of collagen during the healing process: Too much collagen breakdown during remodeling leads to indented (atrophic) scars, while excessive production of new collagen results in raised (hypertrophic or keloid) scars.6-8

Scientists do not understand why some people develop acne scars and others don’t. However, we know that the best way to prevent scar formation is to treat acne early, before scars have a chance to develop.7

When it comes to improving the appearance of scars that have already formed, it is important to be clear of acne before starting scar treatment. Otherwise, you may end up in an endless cycle of treating old scars while new scars form.6

References

- Kircik, L. H. Re-evaluating treatment targets in acne vulgaris: adapting to a new understanding of pathophysiology. J. Drugs Dermatol. 13, s57 – 60 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24918572

- Goodman, G. J. Post-acne scarring: A short review of its pathophysiology. Australas. J. Dermatol. 42, 84 – 90 (2001). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11309028

- Velnar, T., Bailey, T. & Smrkolj, V. The wound healing process: an overview of the cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Int. Med. Res. 37, 1528-1542 (2009). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19930861/

- Saint-Jean, M., Khammari, A., Jasson, F., Nguyen, J.-M. & Dréno, B. Different cutaneous innate immunity profiles in acne patients with and without atrophic scars. Eur. J. Dermatol. 26, 68 – 74 (2016). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27018005

- Shih, B., Garside, E., McGrouther, D. A. & Bayat, A. Molecular dissection of abnormal wound healing processes resulting in keloid disease. Wound Repair Regen. 18, 139 – 153 (2010). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20002895

- Connolly, D., Vu, H. L., Mariwalla, K. & Saedi, N. Acne scarring – pathogenesis, evaluation, and treatment options. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 10, 12-23 (2017). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29344322/

- Fife, D. Practical evaluation and management of atrophic acne scars: tips for the general dermatologist. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 4, 50-57 (2011). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21909457/

- Karppinen, S. M., Heljasvaara, R., Gullberg, D., Tasanen, K. & Pihlajaniemi, T. Toward understanding scarless skin wound healing and pathological scarring. F1000Research 8, F1000 Faculty Rev-787 (2019). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31231509/