The Production of Too Many Skin Cells Results in Dead Skin Cell Accumulation and A Clogged Pore

The Essential Info

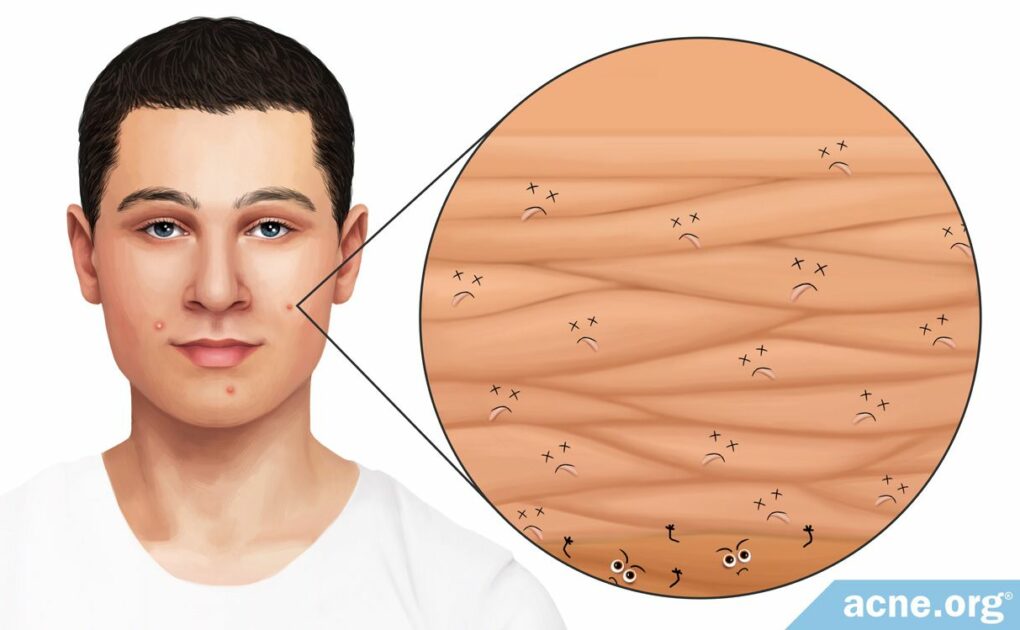

Skin cells play an important role in the formation of acne.

Normal Skin: In normal, healthy skin, the body produces just the right amount of skin cells. Once these skin cells grow old, they die and shed from the skin.

Acne-prone Skin: In acne, skin cells are over-produced. And when these skin cells get old and die, they tend to stick together, resulting in an accumulation of dead skin cells inside pores, which clogs the pore.

The Science

- Skin Renewal in Normal Skin

- Renewal in Acne-prone Skin

- Factors That Cause the Overproduction of Skin Cells

- Factors That Cause Skin Cells to Stick Together

- What Can Be Done About It?

Let’s start by looking at the difference between skin renewal in normal skin vs. acne-prone skin.

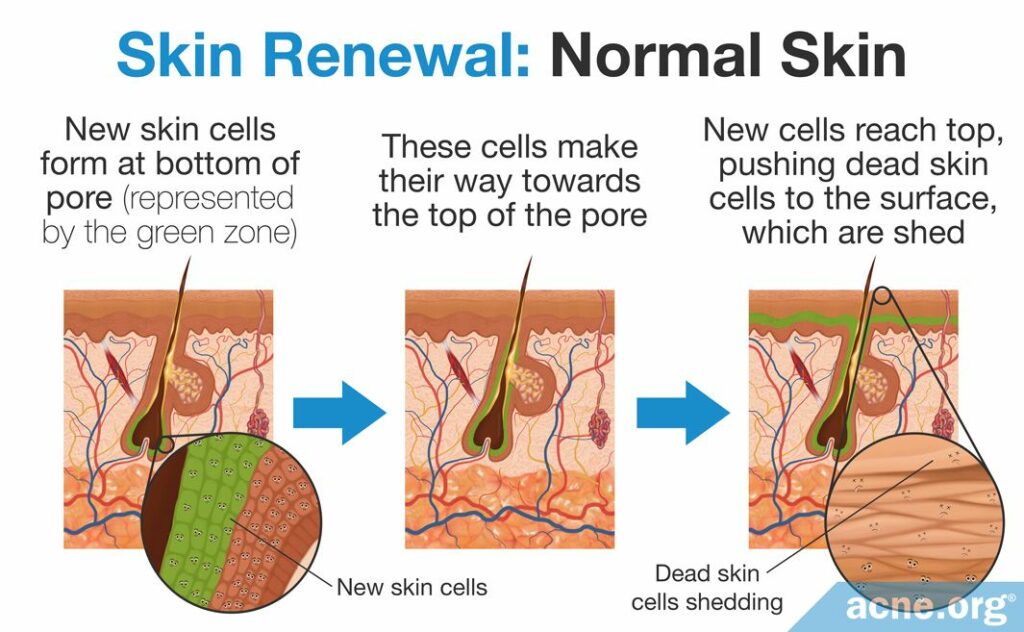

Skin Renewal in Normal Skin

In healthy skin, new skin cells, called keratinocytes, are constantly being produced in the deepest layers of the skin. As these skin cells age, they move towards the surface of the skin. Over the course of a couple of weeks, these skin cells will die and are then called corneocytes. The corneocytes remain for a few weeks and then shed from the skin.1

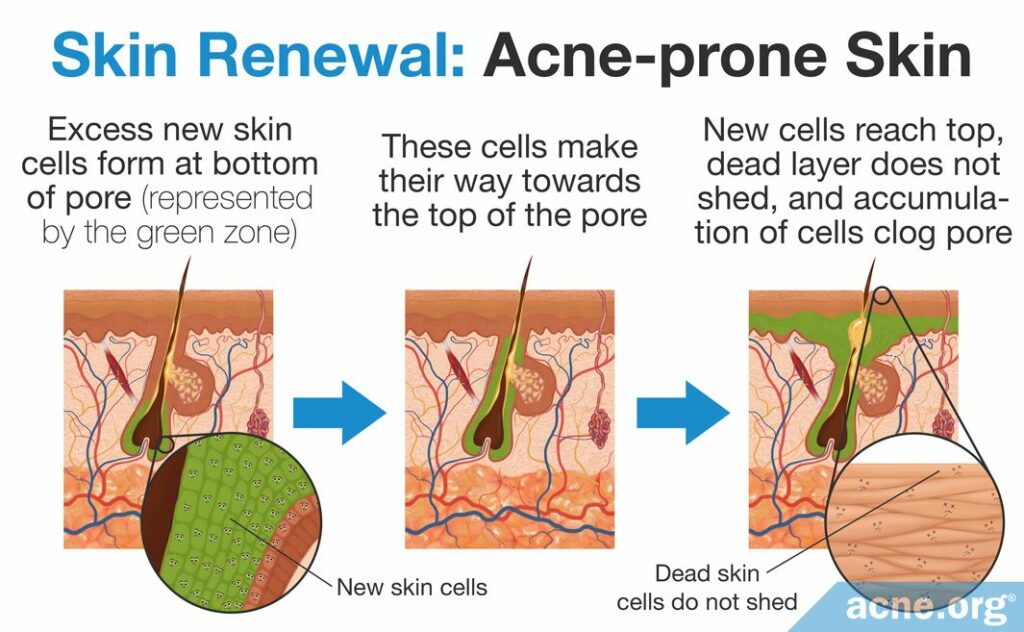

Skin Renewal in Acne-prone Skin

In acne-prone skin, skin cells are produced too fast, about 1.5 times as fast as in healthy skin.2 These skin cells are also stickier than they should be because they contain too much of a sticky protein called keratin. Once these skin cells die, the sticky keratin keeps them stuck together and they do not shed from the skin as they should, instead accumulating inside skin pores. This accumulation gives rise to clogged pores, which can develop into full-fledged acne lesions.

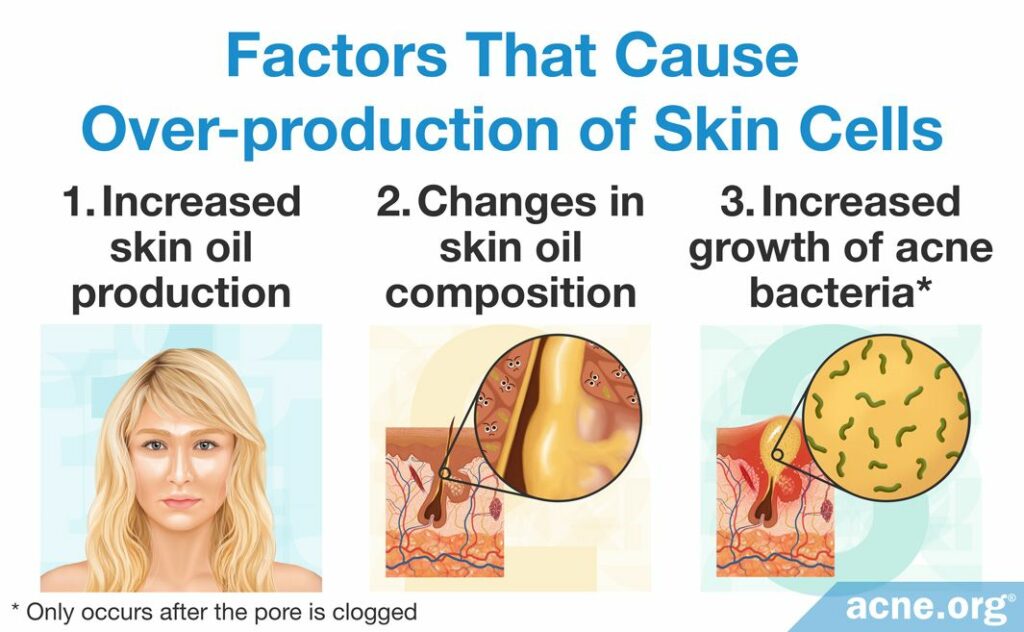

Factors That Cause the Overproduction of Skin Cells

There are three main factors that may stimulate the production of new skin cells:

- Increase in skin oil (sebum): Acne-prone skin produces too much skin oil, called sebum, which is thought to stimulate skin cell production.

- Different makeup of sebum: Sebum is made of a mixture of lipids (oils, waxes, and fatty acids). One main lipid present in sebum, called linoleic acid, seems to be lower in people with acne-prone skin. The low levels of linoleic acid in acne-prone skin may lead to the production of more skin cells.

- Increase in bacteria: A strain of bacteria found in acne lesions, called C. acnes, grows inside clogged pores and feeds on sebum. It is thought that the presence of too many C. acnes bacteria can trigger the production of more skin cells. However, it is important to note that this factor differs from the other two factors since the C. acnes bacteria only trigger the production of new skin cells after a pore has already clogged, in essence strengthening an already clogged pore.2-5

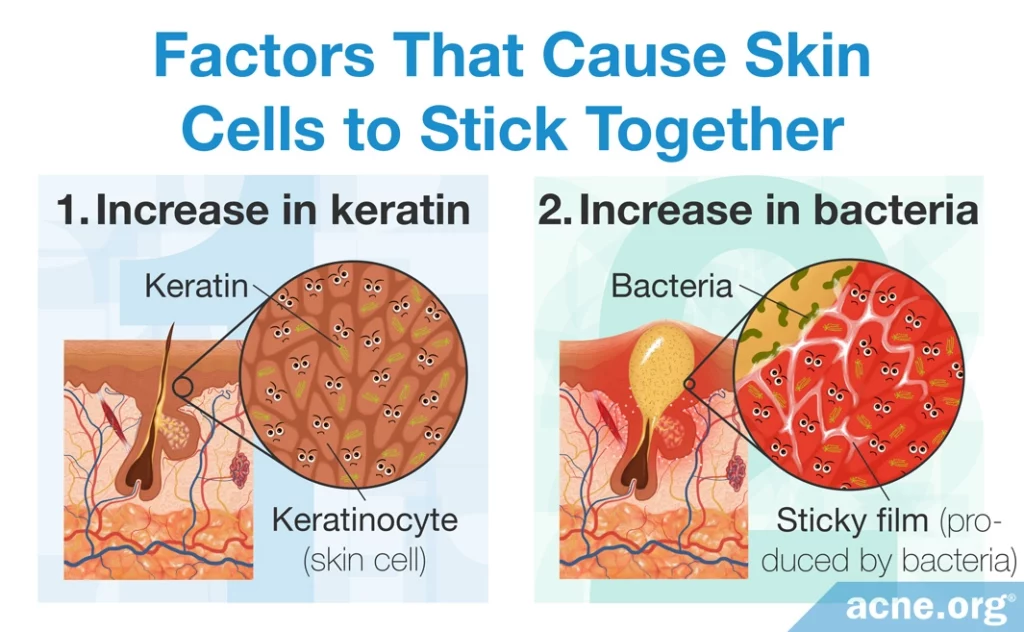

Factors That Cause Skin Cells to Stick Together

Once there are too many skin cells, the other problem is that these cells stick together and don’t shed as they should.

In normal skin, skin cells don’t stick together inside the pore, but in acne-prone skin, two main factors cause this to happen.

- Increase in keratin: In acne-prone skin, there is more of a sticky protein called keratin in the skin. The abundance of keratin results in dead skin cells sticking together.

- Increase in bacteria: When C. acnes grows inside the pore, it produces a sticky film all its own that further leads to skin cells sticking together instead of shedding as they should.2,3,6

What Can Be Done About It?

When it comes to counteracting the accumulation of dead skin cells, hydroxy acids like salicylic acid or glycolic acid can help. These acids stimulate exfoliation, which is the natural shedding of dead skin cells from the skin surface. Hydroxy acids loosen the connections between dead skin cells and make them less sticky, thus helping the cells to shed in a timely manner.6,7 While hydroxy acids on their own will not clear acne completely, they are an effective addition to an anti-acne medication regimen.

References

- Aldana, O. L., Holland, D. B. & Cunliffe, W. J. Variation in pilosebaceous duct keratinocyte proliferation in acne patients. Dermatology 196, 98 – 99 (1998). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9557240

- Knaggs, H. E., Holland, D. B., Morris, C., Wood, E. J. & Cunliffe, W. J. Quantification of cellular proliferation in acne using the monoclonal antibody Ki-67. J Invest Dermatol 102, 89 – 92 (1994). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8288915

- Das, S. & Reynolds, R. V. Recent advances in acne pathogenesis: implications for therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol 15, 479 – 488 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25388823

- Makrantonaki, E., Ganceviciene, R. & Zouboulis, C. An update on the role of the sebaceous gland in the pathogenesis of acne. Dermatoendocrinol 3, 41 – 49 (2011). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3051853/

- Duckney, P. et al. The role of the skin barrier in modulating the effects of common skin microbial species on the inflammation, differentiation and proliferation status of epidermal keratinocytes. BMC Res Notes 6, 474 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24245826

- Burkhart, C. G. & Burkhart, C. N. Expanding the microcomedone theory and acne therapeutics: Propionibacterium acnes biofilm produces biological glue that holds corneocytes together to form plug. J Am Acad Dermatol 57, 722-724 (2007). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17870436/

- Decker, A. & Graber, E. M. Over-the-counter acne treatments: A review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 5, 32-40 (2012). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22808307/

- Lekakh, O., Mahoney, A. M., Novice, K. et al. Treatment of acne vulgaris with salicylic acid chemical peel and pulsed dye laser: A split face, rater-blinded, randomized controlled trial. J Lasers Med Sci 6, 167-170 (2015). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26705462/

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products