Inflammation Plays a Central Role in All Stages of Acne Development

The Essential Info

The body’s immune system is responsible for creating inflammation. It does this in response to anything that it sees as “foreign” or as an “invader.” This is normally a good thing because the inflammation serves to heal tissue damage or fight off infection. In acne, however, the immune system does not work as it should, and produces inflammation in the wrong places at the wrong times.

It turns out that inflammation is the starting point for acne lesion formation right at the start of an initial clogged pore, and inflammation remains present throughout the entire cycle of acne lesion development and healing.

Because inflammation is now known to be so ubiquitous in acne, scientists now consider acne a chronic inflammatory disease.

The Science

The Role of Inflammation in the Development of Acne

There are two major theories of acne formation.

- The newer theory points to inflammation as the main factor in acne development. The more we learn, the more this theory asserts itself.

- The traditional theory contends that inflammation plays a much less important role. The more we learn, the more outdated this theory becomes.

Research in recent years has led to more scientific support for the newer theory, and to the classification of acne as a chronic inflammatory disease. The development of acne is a complex process that involves several steps, beginning with inflammation in the skin even when no acne is yet present. This article will explore the role that inflammation may play, according to the newer theory, in each of these steps.

Caution: Deep science ahead! This is interesting stuff, but it will get involved.

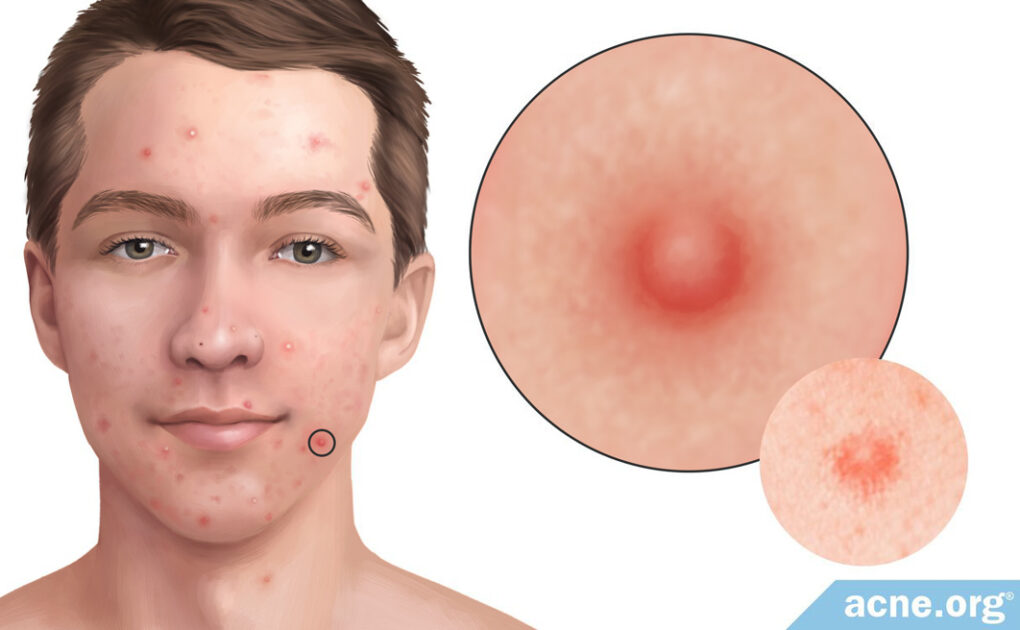

Inflammation is present even in areas of the skin with no acne

Acne begins with small amounts of inflammation near skin pores. An increasing amount of scientific evidence suggests that there are several inflammatory molecules present at the onset of acne formation. In other words, inflammation is present even before the acne lesion begins to form, and this inflammation triggers the earliest steps in the formation of acne.

In a study in which scientists examined the skin of people with mild-to-moderate acne, the researchers found that in at least 28% of the 25 acne patients studied, acne lesions developed from healthy-looking skin. This discovery led the researchers to assume that acne development begins with an inflammatory process that is undetectable to the naked eye.

In short, all acne is inflammatory. Historically, doctors have used the term “non-inflammatory acne” to describe acne lesions that have no redness in or around them (whiteheads and blackheads). Our new understanding of the development of acne shows that this term is inaccurate, but the medical community still uses this term to distinguish mild acne breakouts without red, sore lesions.1

A 2018 article in the medical journal Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery noted, “‘Noninflammatory acne’ is thus a misnomer; it appears that all primary acne lesions are inflammatory.”1

To determine exactly what inflammatory processes occur in early acne lesions, several research studies have identified a number of inflammatory indicators that show up near pores that eventually become acne lesions. These include:2,3

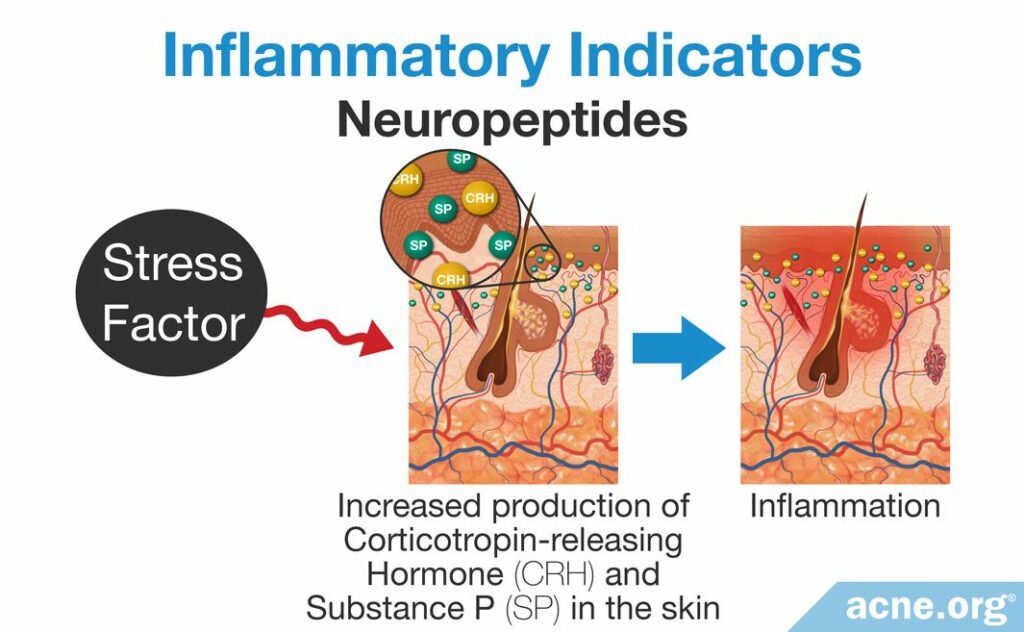

Study 1 – Neuropeptides: Neuropeptides are proteins found in the body’s nerves and nervous system. There are several types of neuropeptides, but only two are associated with early acne development.

- Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH)

- Substance P (SP)

The body increases the amount of CRH and SP in the blood in response to stress. Stress can be either mental or physical. This means that if a person is particularly stressed, or if the body is under duress due to an infection or a wound, then the nervous system will increase the levels of these substances in the blood. Researchers have hypothesized that this may lead to more CRH and SP in the skin, both of which can trigger an inflammatory response that may result in acne. To support this idea, researchers have found that acne-prone skin possesses higher levels of CRH and SP than the skin of non-acne patients. Scientists believe that their presence in the skin may trigger the earliest inflammation involved in the acne lesion.4

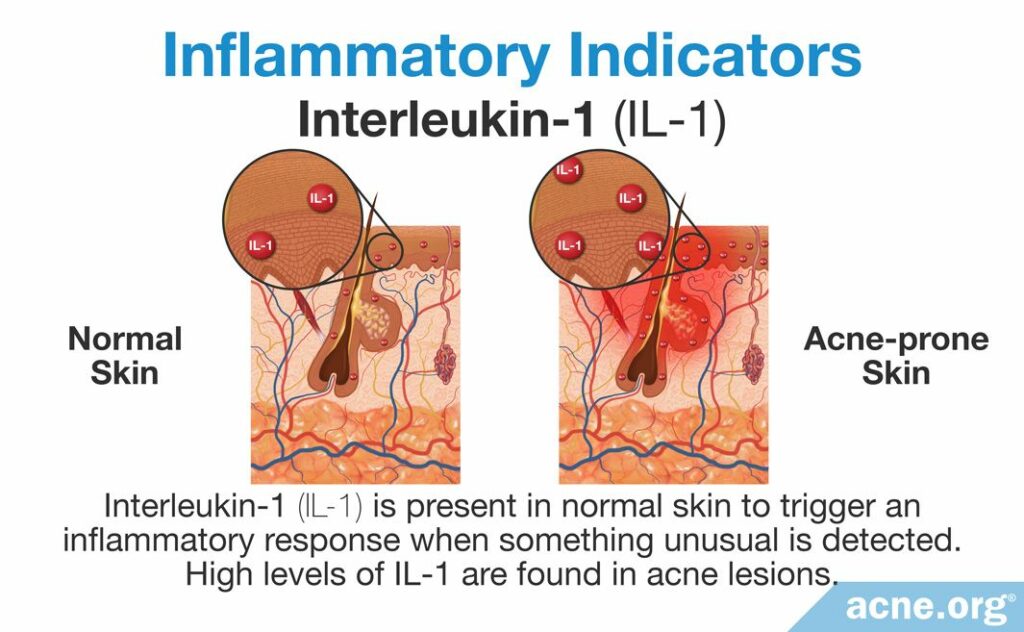

Study 2 – Interleukin-1: Interleukin-1 (IL-1) is a type of inflammatory molecule called a cytokine. It is released from skin cells and skin oil-producing glands, which are attached to the sides of skin pores. Normally, IL-1 acts like a patrolling soldier by traveling throughout the skin, looking for bacteria that could cause an infection.

IL-1 is always present in the skin and is always ready to respond and trigger a large inflammatory response if it detects anything unusual. In acne, high levels of IL-1 are found in early acne lesions. In fact, some studies have found that up to 76% of acne lesions contain elevated IL-1 levels. This suggests that it may be responding to a perceived threat near the early acne lesion, and triggering a small inflammatory response–which may trigger the development of a comedone.4

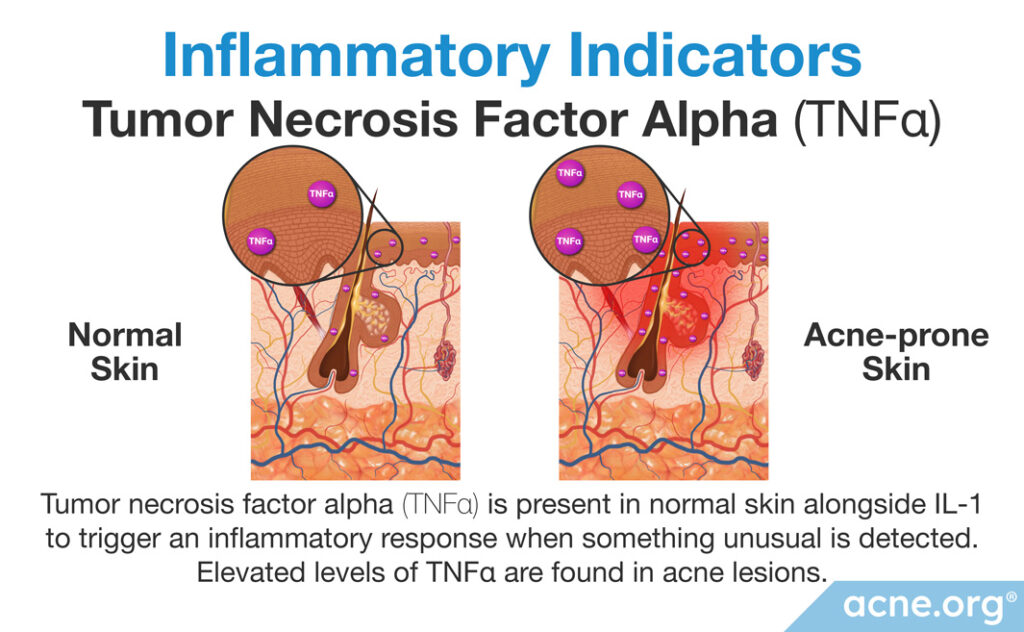

Study 3 – Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα): TNFα is another inflammatory cytokine that works with IL-1 to activate the immune response.5 Normally, skin oil glands release a certain amount of TNFα, but research shows that this amount is significantly higher in the skin of people with acne. This increase in TNFα may be the body’s way of responding to a perceived threat, such as increased growth of acne bacteria (C. acnes) in skin pores.6 As with other signs of inflammation, scientists find that elevated levels of TNFα are present in all kinds of acne lesions, even so-called “non-inflammatory” lesions.7

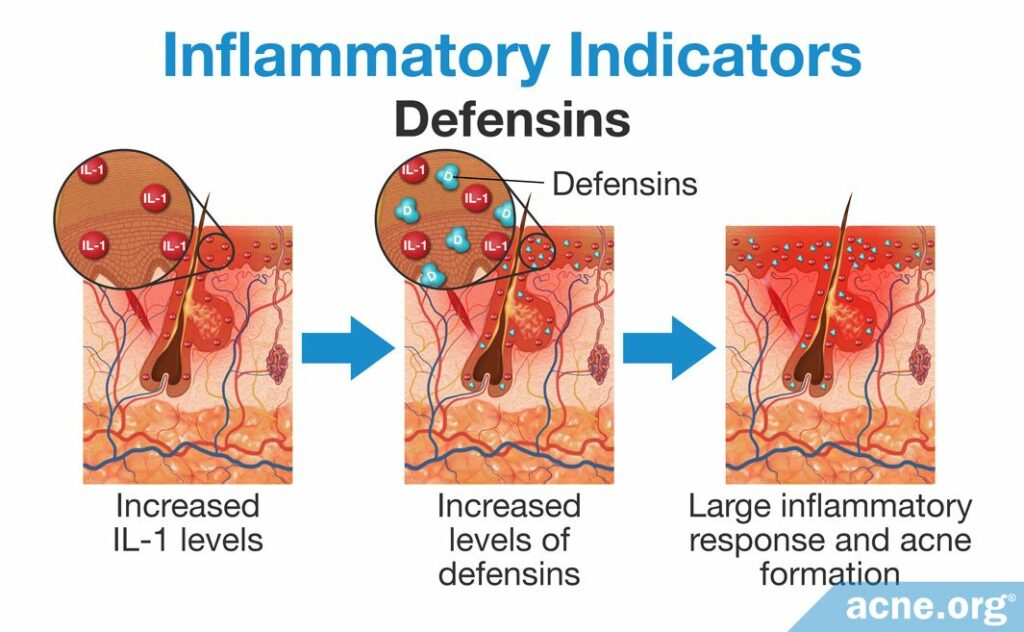

Study 4 – Defensins: Often, when IL-1 levels increase due to a perceived threat, the activity and concentration of defensins, another inflammatory molecule that helps protect the skin from bacteria, are also upregulated. In other words, defensins are a secondary response to the initial increase in IL-1. When activated, they then trigger a larger inflammatory response, which could bring about acne.4

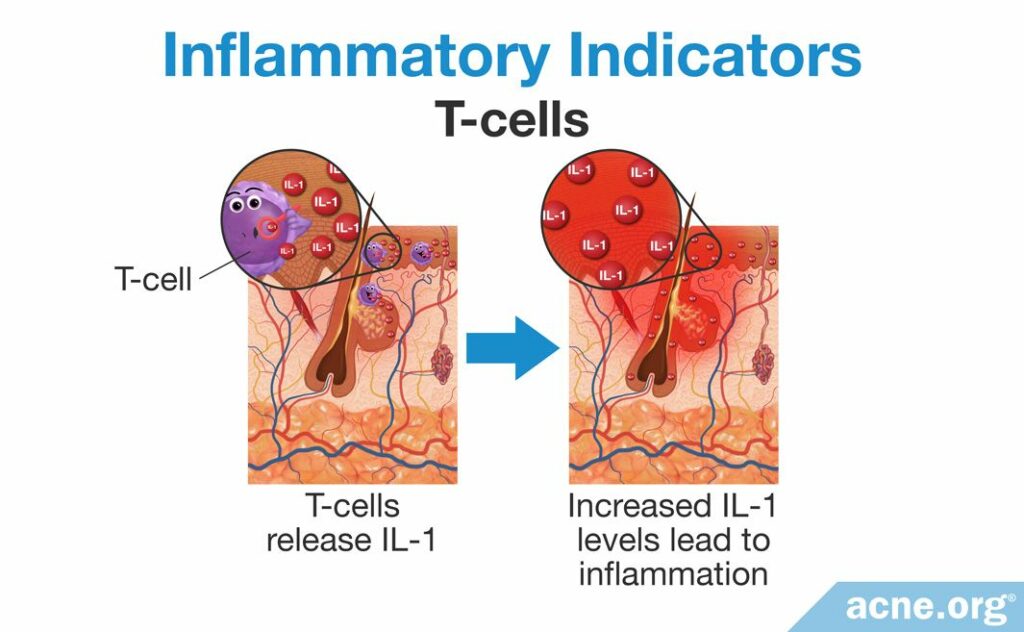

Study 5 – T Cells: T cells are a specific type of white blood cell that contributes to inflammation by releasing IL-1 and also triggers other inflammatory responses. Researchers have found that T cells surround clogged pores and hypothesize that they may contribute to them.8

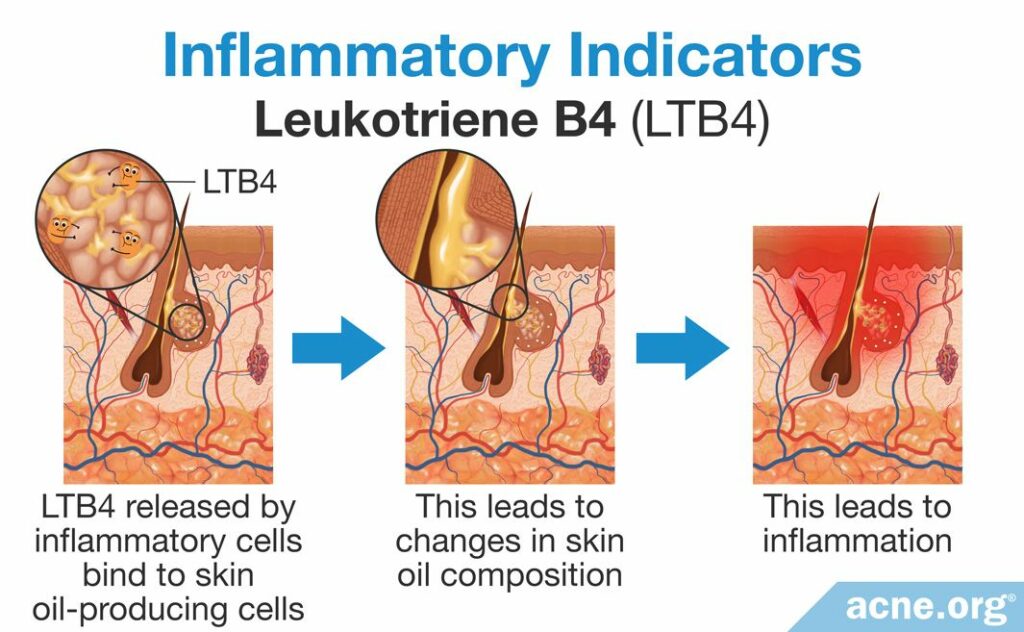

Study 6 – Leukotriene B4: Leukotriene B4 is an inflammatory molecule that works by changing how skin oil cells, called sebocytes, function. It attaches to sebocytes and triggers them to change the composition of skin oil. Research has found that changes to the composition of skin oil can trigger inflammation. Therefore, the changes in skin oil triggered by leukotriene B4 can lead to more inflammation in the earliest acne stage.8

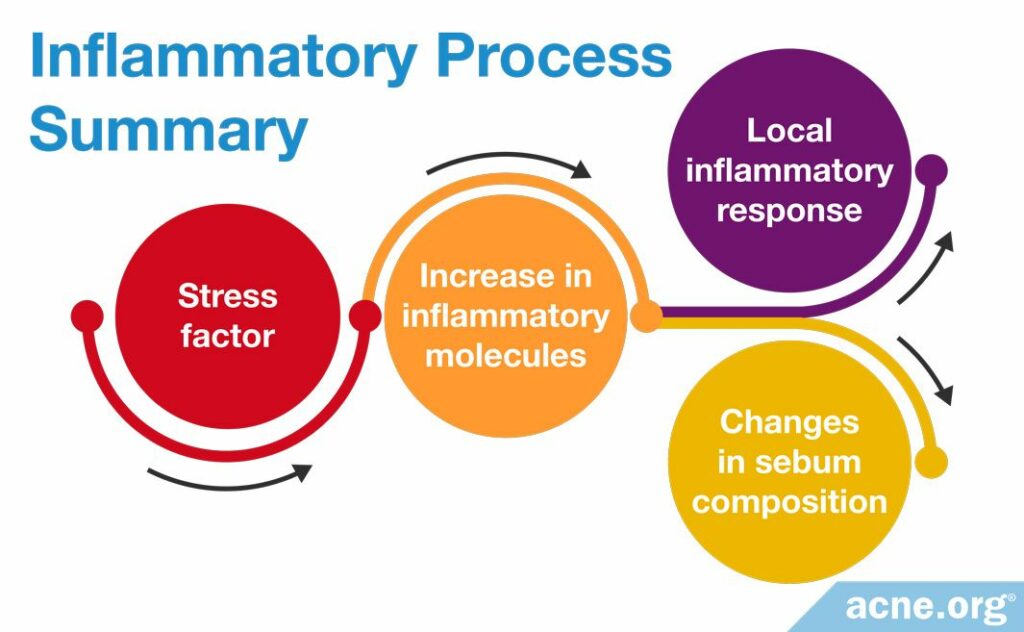

To sum it up, stress may increase the levels of CRH and SP, which triggers the cytokines IL-1 and TNFα to activate defensins, which, in conjunction with T cells and leukotriene B4-induced sebum changes, may result in a clogged pore and eventually, an acne lesion.

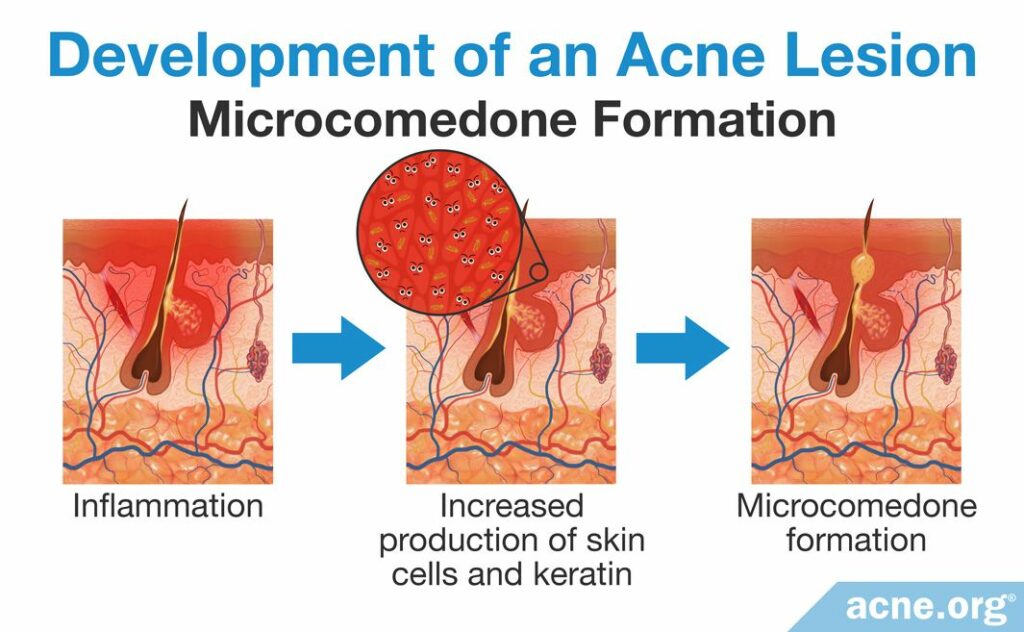

Once inflammation is present, it triggers the formation of a clogged pore (comedone)

Once inflammation begins in the skin, it triggers a process called hyperkeratinization, which occurs when the skin produces too many skin cells (keratinocytes) and too much protein (keratin). This causes the pore to narrow and clog initially, forming the very first type of clogged pore in acne, called a microcomedone.8

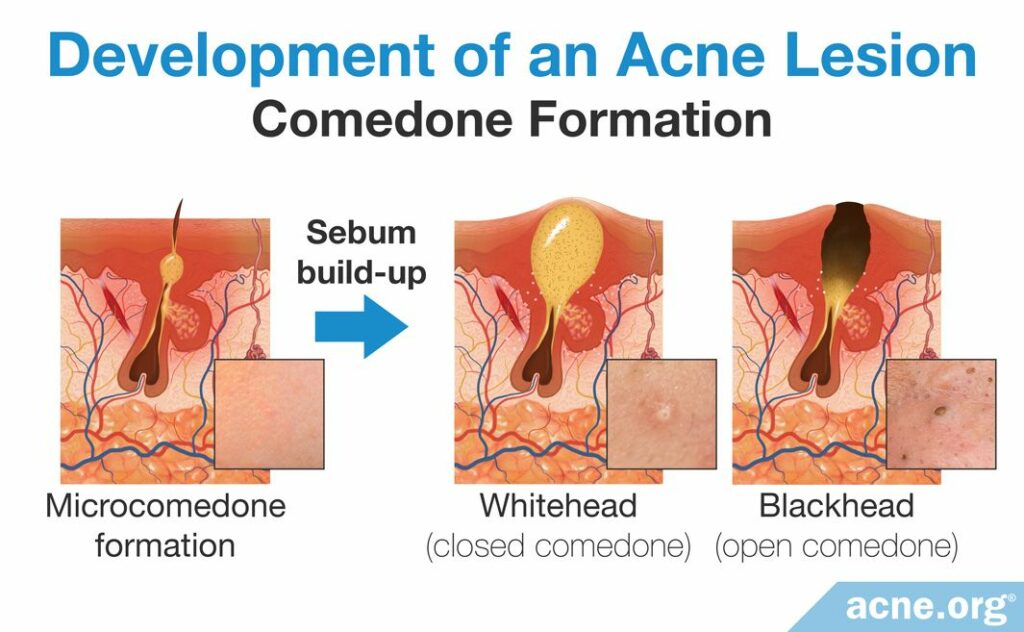

A microcomedone then leads to a buildup of skin oil (sebum) inside the pore

When a pore is clogged, skin oil, called sebum, begins to build up inside of it. When there is a large enough buildup, it becomes visible to the naked eye. At this point, the acne lesion is called a comedone, more commonly known as a whitehead or blackhead.

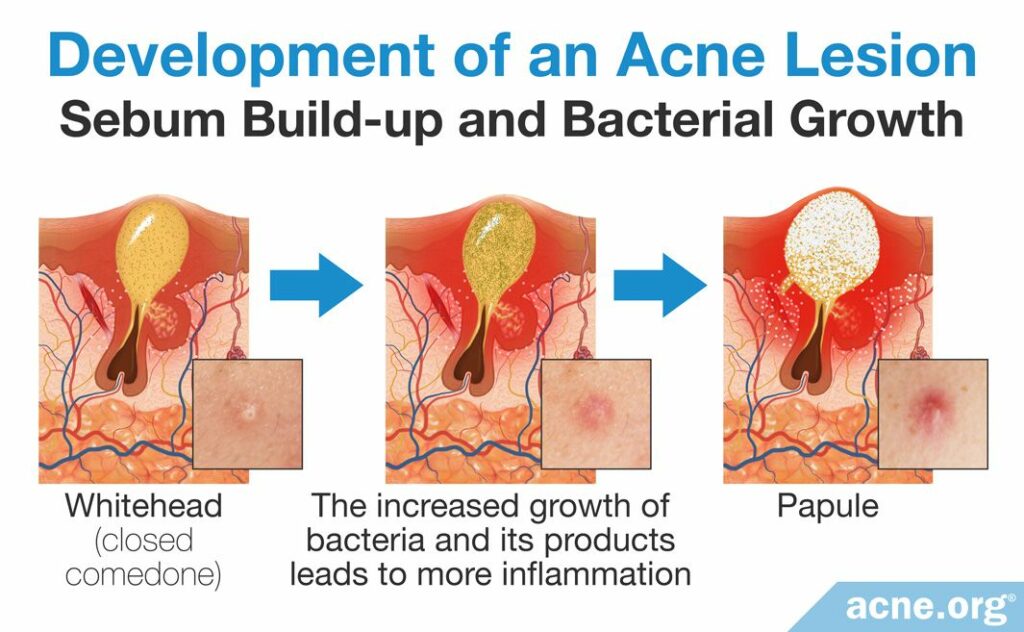

Sebum buildup leads to bacterial growth and additional inflammation

Inside of a comedone is little or no oxygen, because the clog prevents the entrance of it. The low-oxygen environment allows for acne bacteria, called Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes) to grow rapidly. The immune system views the overgrowth of these bacteria as “invaders,” which in turn worsens inflammation in the acne lesion. The immune system reacts with:

- Release of interleukins (IL-6, IL-8, and IL-12): These interleukins are inflammatory molecules similar to IL-1 that play a slightly different role in the skin. They are released when the rapidly growing C. acnes bacteria attach to the immune cells that surround the comedone. In other words, C. acnes attaches to immune cells when it overgrows, and this triggers the immune cells to release IL-6, IL-8, and IL-12. When released near the comedone, these 3 types of interleukins recruit other immune cells, called neutrophils, which begin attacking the comedone. The neutrophil attacks may cause the pore wall to rupture, which dramatically increases inflammation.8-10

- Release of bacterial metabolites: When bacteria is abundant, it releases a large amount of waste products, called bacterial metabolites. C. acnes metabolites include chemicals and proteins that can trigger a more severe inflammatory response in and around the growing acne lesion. The increase in inflammation near the comedone attracts more neutrophils to the area, which attack its wall. The neutrophil attacks may cause the pore to rupture, leading to dramatically increased inflammation.8

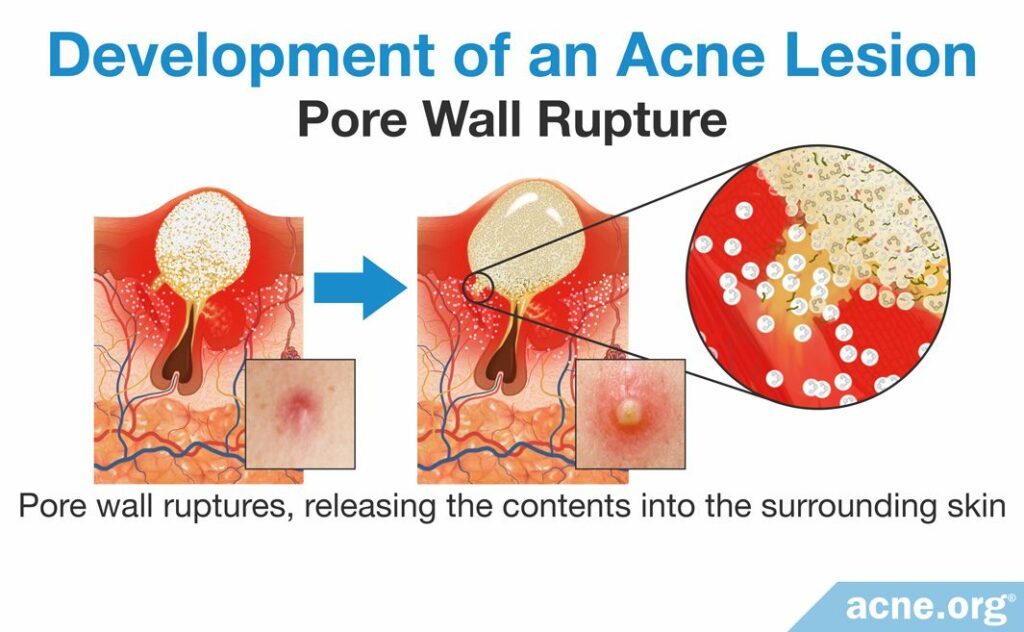

Pore wall rupture leads to dramatically increased inflammation

When the pore wall ruptures, it releases the contents of the pore into the surrounding skin. The release of sebum and bacteria into the skin causes additional inflammation, which results in red, inflamed acne lesions like papules, pustules, nodules, and cysts.

Conclusion

Inflammation plays a central role in every stage of acne development. A growing body of scientific evidence indicates that inflammation may even be present from the onset of acne development, which begins with inflammatory molecules present around pores. Inflammation then stimulates an overproduction of skin cells. This narrows the pore, causing a comedone. As the comedone fills with sebum and C. acnes, the inflammation in and around the pore grows larger, and eventually causes the pore wall to break. At this point the pore’s contents are released into the surrounding skin, which causes even more inflammation–resulting in red and painful papules, pustules, nodules, and cysts.

References

- Tan, J. K. L., Stein Gold, L. F., Alexis, A. F. & Harper, J. C. Current concepts in acne pathogenesis: Pathways to inflammation. Semin Cutan Med Surg 37, S60 – S62 (2018). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30192343

- Danby, F. Ductal hypoxia in acne: Is it the missing link between comedogenesis and inflammation?J Am Acad Dermatol 70, 948 – 949 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24742839

- Do, T. et al. Computer-assisted alignment and tracking of acne lesions indicate that most inflammatory lesions. arise from comedones and de novo. J Am Acad Dermatol 58, 603 – 608 (2008). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18249468

- Tanghetti, E. The role of inflammation in the pathology of acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 6, 27 – 35 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3780801/

- Ott, L. W., Resing, K. A., Sizemore, A. W., Heyen, J. W., Cocklin, R. R., Pedrick, N. M., Woods, H. C., Chen, J. Y., Goebl, M. G., Witzmann, F. A. & Harrington, M. A. Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha- and interleukin-1-induced cellular responses: coupling proteomic and genomic information. J Proteome Res 6, 2176-2185 (2007). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17503796/

- Kurokawa, I., Danby, F. W., Ju, Q., Wang, X., Xiang, L. F., Xia, L., Chen, W., Nagy, I., Picardo, M., Suh, D. H., Ganceviciene, R., Schagen, S., Tsatsou, F. & Zouboulis, C. C. New developments in our understanding of acne pathogenesis and treatment. Exp Dermatol 18, 821-832 (2009). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19555434/

- Ozkanli, S., Karadag, A. S., Ozlu, E., Uzuncakmak, T. K., Takci, Z., Zemheri, E., Zindancı, I., Akdeniz, N. A comparative study of MMP-1, MMP-2, and TNF-α expression in different acne vulgaris lesions. Int J Dermatol 55, 1402-1407 (2016). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27421059/

- Degitz, K., Placzek, M., Borelli, C. & Plewig, G. Pathophysiology of acne. JDDG 5, 316 – 323 (2007). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17376098

- Kim, J. Review of the innate immune response in acne vulgaris: activation of toll-like receptor 2 in acne triggers inflammatory cytokine responses. Dermatology 211, 193 – 198 (2004). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16205063

- Cruz, S., Vecerek, N. & Elbuluk, N. Targeting inflammation in acne: Current treatments and future prospects. Am J Clin Dermatol 24, 681-694 (2023). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37328614/

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products