All Races and Ethnicities Get Indented Acne Scars. There Is Not Enough Data to Tell If Any Ethnic Group Is More Prone to These Types of Scars.

The Essential Info

Indented (so-called atrophic) scars are the most common type of acne scars. Research shows that people of all ethnic and racial backgrounds can develop these scars. However, very few studies have compared people of different ethnicities to see whether some are more prone to indented scars than others.

What we do know is that once scars develop, they are impossible to fully remove, so treating active acne is the best thing a person of any ethnicity can do to prevent future scars.

The Science

Over 90% of people with acne experience some degree of scarring in their lifetime.1 The more severe the acne, the more severe the scarring tends to be as well.2,3

Having visible scars, especially on the face, can be distressing and can sometimes damage self-esteem and even produce anxiety or depression. Unfortunately, left to their own devices, scars don’t necessarily fade over time.

When it comes to treating scars, while a variety of treatments can improve scars to some degree, none can fully remove them. Therefore, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, and the best prevention is to treat acne at an early stage.

Let’s take a quick look at why acne scars form and what distinguishes indented scars from other types of acne scars. Then we’ll delve into the evidence on which ethnicity is more prone to indented scars. Spoiler: We don’t know if any ethnicity is more likely to develop indented scars, but it’s clear no ethnic group is exempt.

A 30-second Crash Course on Why Acne Scars Form

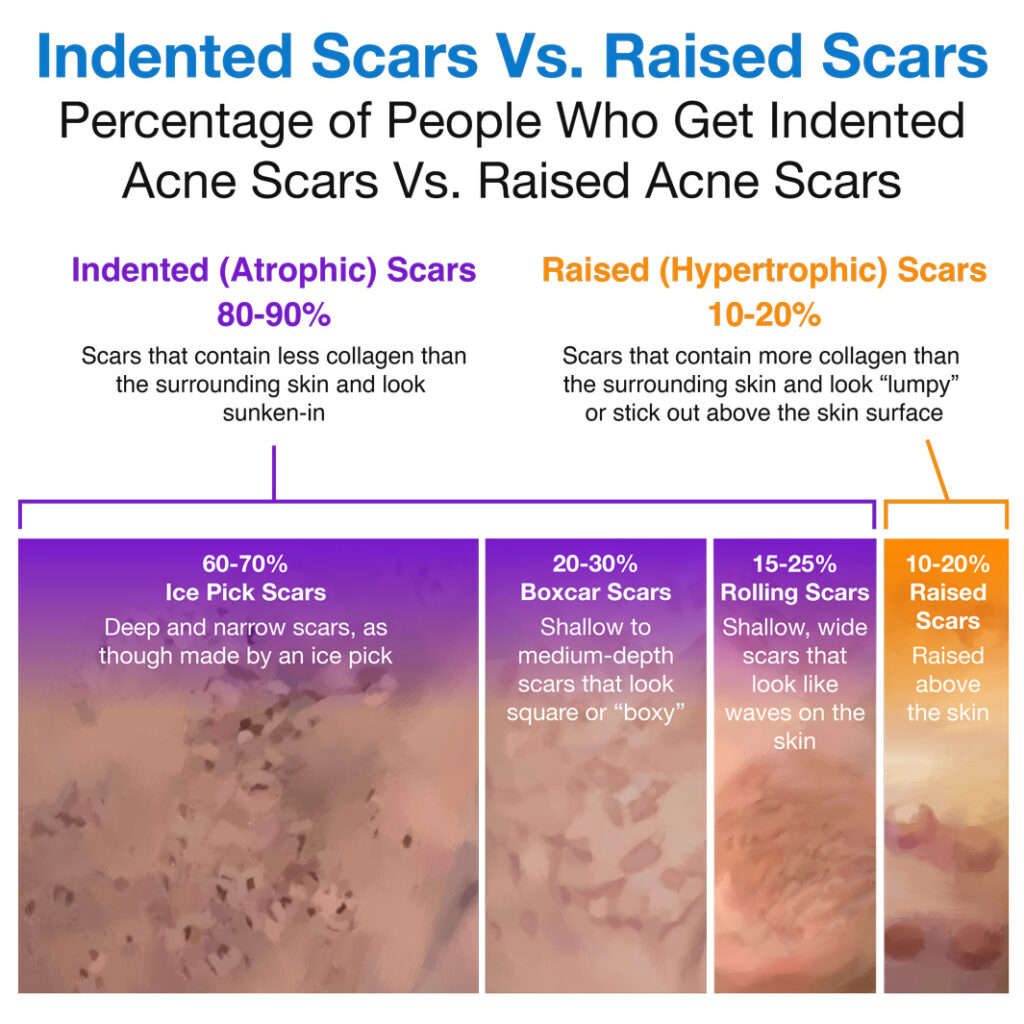

An acne scar forms anytime an acne lesion heals imperfectly. Normally, the body aims to replace acne lesions with new, healthy skin tissue consisting of skin cells and a protein called collagen. If something disrupts this healing process, the new skin can end up with either too little collagen or too much collagen, resulting in a visible scar.

Scientists speculate that what disrupts the healing process may be inflammation that goes on too long. A short period of inflammation is a normal part of the healing process, seen as redness, swelling, and soreness whenever any type of cut or lesion first starts to heal. However, in people with acne, inflammation is constantly brewing in the skin, and the more severe the acne, the more inflammation can go into overdrive. This prolonged inflammation may explain why the healing process often goes off-track, resulting in scars.2,3

Now let’s take a look at the research on how common indented acne scars are in different ethnic groups.

Studies Comparing Acne Scarring in Different Ethnic Groups

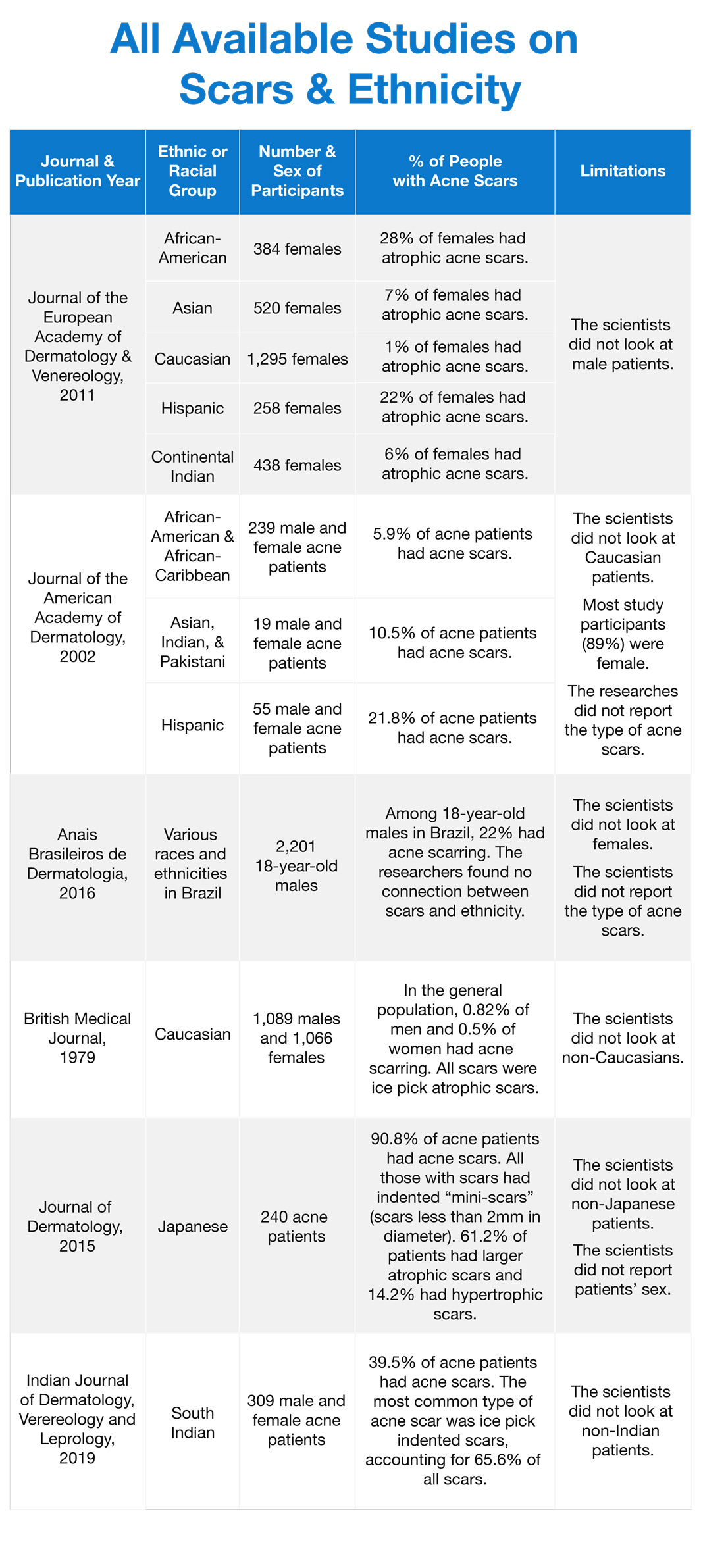

The results of the research so far are contradictory. Two studies that have compared acne scarring in multiple ethnicities have agreed only on one thing: that Hispanic females may be among the most prone to indented scars. However, when it came to other ethnicities, the studies came up with contradictory findings.

Several other studies have only looked at one or two ethnicities at a time. These studies found that people of each ethnicity had some acne scars, but couldn’t answer the question of whether any one ethnicity was more prone to scars than others. Let’s take a closer look at the research.

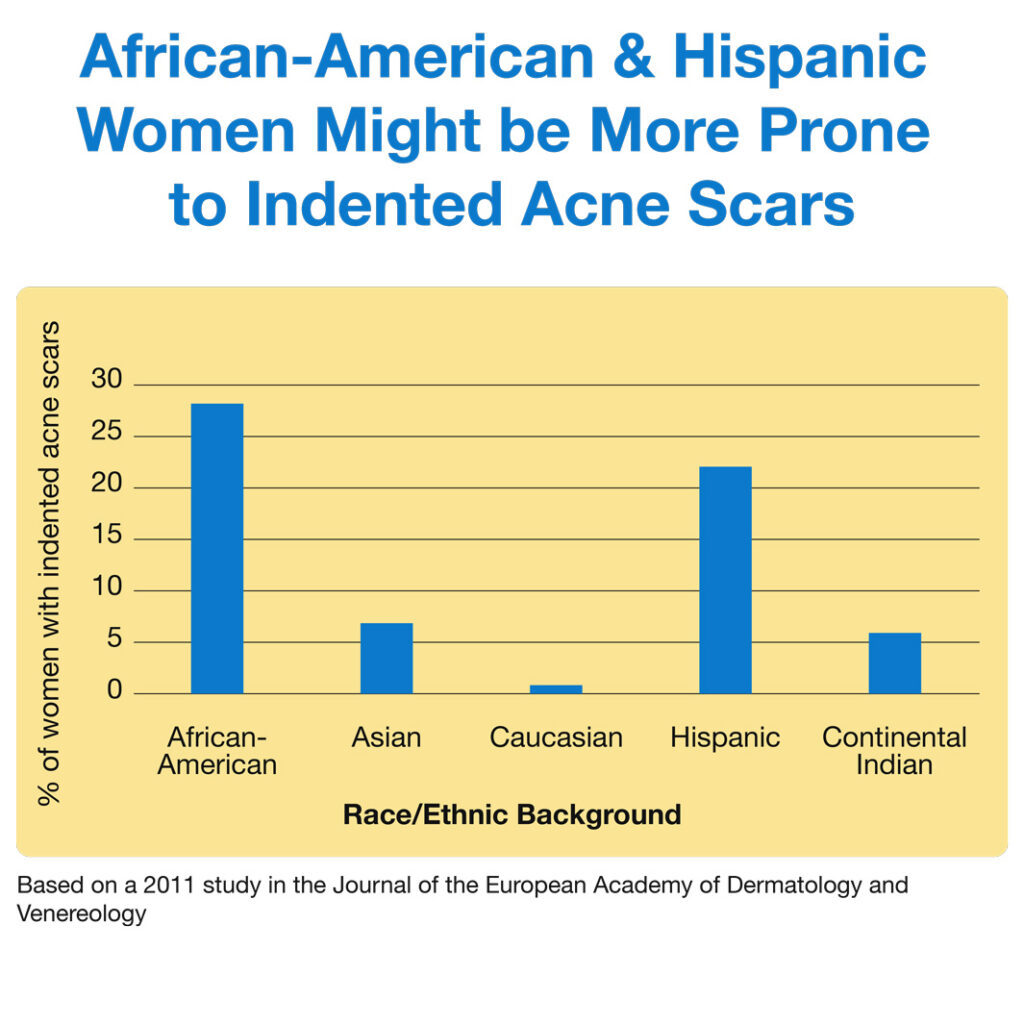

One study, published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology in 2011, has performed a comprehensive comparison of all the major racial groups to see how common acne scars are in each group. This study only looked at women and concluded that African-American and Hispanic women tend to develop more indented scars compared to women of Asian and Indian descent and Caucasian women.6

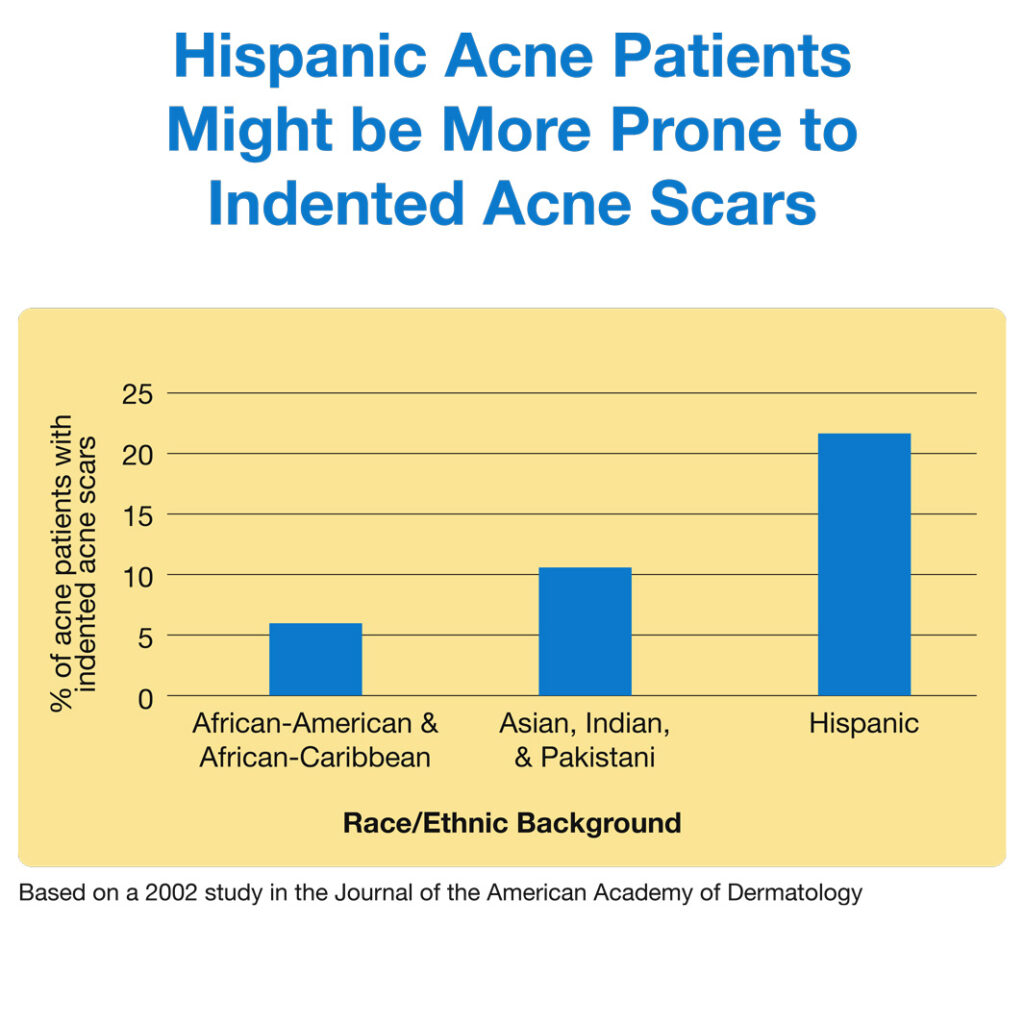

Another, smaller study that did not look at all ethnicities, was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in 2002. This study also looked at mostly women but did include a few men.

Unlike the previous study, this study found that people of Hispanic background were most prone to indented acne scars. People of Asian, Indian, and Pakistani background, who were grouped together, came in second, followed by people of African-American and African-Caribbean descent. Unfortunately, the study did not include any Caucasian participants. We should also note that there were only 19 total participants of Asian, Indian, and Pakistani background, which is far too few for us to draw any conclusions about an entire racial group.7

Since the two studies above contradict each other, it is hard to reconcile their findings to come to any overall conclusion. Both studies do suggest that Hispanic females might be relatively prone to indented acne scarring compared to some other ethnicities.

Several other studies have looked only at one or a few specific ethnicities.8-11 As we will see, each study looked at different types of participants:

- Some studies examined only acne patients, while others looked at people in the general population.

- Some studies included only females, while others looked at both sexes.

This makes comparisons between the studies very difficult, so we cannot say whether people of any particular ethnic background are more prone than others to indented acne scars. All we can say for sure is that no ethnic or racial group is exempt: everyone can develop indented acne scars to some degree.12,13

The table below summarizes the findings of all the studies we have on this topic to date. The takeaway is that females of Hispanic background may be among the most prone to indented scars, but the jury is still out on how other ethnicities rank in terms of scarring.

Treating Indented Acne Scars

Whatever your ethnicity, finding the right treatment for your acne scars can be a daunting task. There are many treatment options available, which can be combined for better results. Scar treatments fall into three classes:

- Resurfacing treatments: These procedures produce a controlled injury to the skin in order to stimulate the skin to produce new collagen. Examples of resurfacing treatments include laser therapy, chemical peels, and dermabrasion.

- Lifting treatments: These procedures aim to smooth out the skin by introducing material like fat into deeper layers of the skin. Examples of lifting treatments include filler injections and fat transfer.

- Excisional treatments: These procedures aim to remove the scarred skin completely so that the body produces new skin to replace it. An example of excisional treatments is punch excision, a technique in which a doctor cuts out each scar using a special tool and stitches together the edges of the hole left over from the scar.1,2

Certain treatments work better for specific scar types. Since most people tend to have more than one type of scar, it may be necessary to combine several different treatments for best results. However, no treatment can completely remove scars. Therefore, it is important to treat acne at an early stage. Preventing lesions from becoming more severe is the best thing you can do to minimize future scarring.

References

- Fife, D. Practical evaluation and management of atrophic acne scars: tips for the general dermatologist. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 4, 50-7 (2011). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21909457/

- Hession, M. T. & Graber, E. M. Atrophic acne scarring: a review of treatment options. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 8, 50-8 (2015). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25610524/

- Connolly, D., Vu, H. L., Mariwalla, K. & Saedi, N. Acne scarring – pathogenesis, evaluation, and treatment options. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 10, 12-23 (2017). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29344322/

- Gozali, M. V. & Zhou, B. Effective treatments of atrophic acne scars. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 8, 33-40 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4445894/

- Fabbrocini, G., Annunziata, M. C., D’Arco, V., De Vita, V., Lodi, G., Mauriello, M. C., Pastore, F. & Monfrecola, G. Acne scars: pathogenesis, classification and treatment. Dermatol Res Pract. 2010, 893080 (2010). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20981308/

- Perkins, A. C., Cheng, C. E., Hillebrand, G. G., Miyamoto, K. & Kimball, A. B. Comparison of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris among Caucasian, Asian, Continental Indian and African American women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 25, 1054-60 (2011). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21108671/

- Taylor, S. C., Cook-Bolden, F., Rahman, Z. & Strachan, D. Acne vulgaris in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 46 (2 Suppl Understanding), S98-106 (2002). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11807471/

- Cunliffe, W. J. & Gould, D. J. Prevalence of facial acne vulgaris in late adolescence and in adults. Br Med J. 1, 1109-1110 (1979). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1598727/?page=1

- Lauermann, F. T., Almeida, H. L. Jr, Duquia, R. P., Souza, P. R. & Breunig, Jde A. Acne scars in 18-year-old male adolescents: a population-based study of prevalence and associated factors. An Bras Dermatol. 91, 291-5 (2016). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27438194/

- Hayashi, N., Miyachi, Y. & Kawashima, M. Prevalence of scars and “mini-scars”, and their impact on quality of life in Japanese patients with acne. J Dermatol. 42, 690-6 (2015). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25916427/

- Adityan, B. & Thappa, D. M. Profile of acne vulgaris–a hospital-based study from South India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 75, 272-8 (2009). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19439880/

- Heng, A. H. S. & Chew, F. T. Systematic review of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Sci Rep. 10, 5754 (2020). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32238884/

- Silverberg, J. I. & Silverberg, N. B. Epidemiology and extracutaneous comorbidities of severe acne in adolescence: a U.S. population-based study. Br J Dermatol. 170, 1136-42 (2014). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24641612/

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products