While Chemically Similar, They Have Differences: Retinol Is Over-the-counter, Weaker, and Comes with Less Side Effects, Whereas Retinoids Are Prescription, Stronger, and Come with More Side Effects

The Essential Info

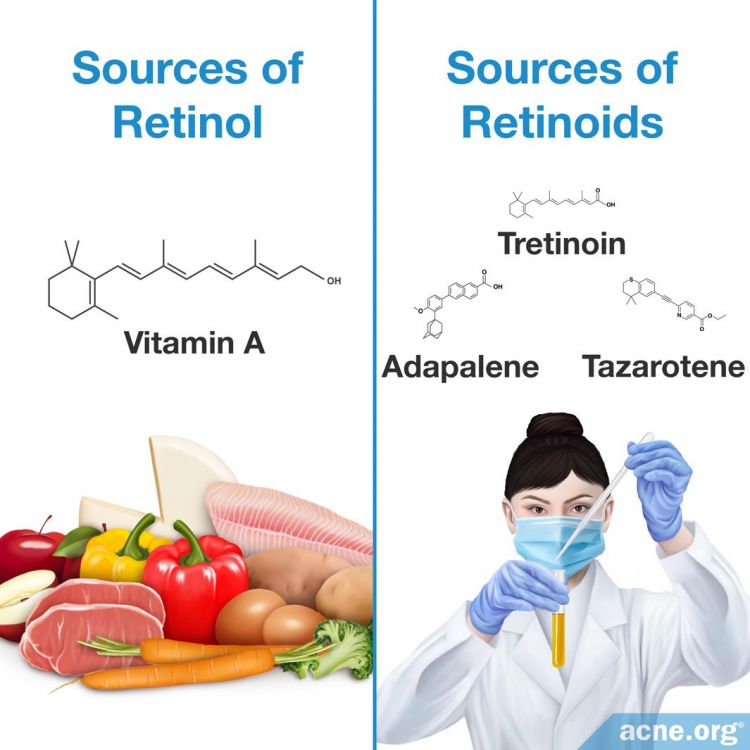

You have probably heard commercials for anti-aging creams touting the benefits of retinol. You may also have heard about prescription anti-acne gels/creams that contain retinoids (tretinoin, adapalene, tazarotene).

The names “retinol” and “retinoids” sound similar, and that’s because they are chemically similar compounds that are derived from vitamin A. However, they have subtle yet important differences that result in unique therapeutic effects.

Retinol:

- Available over-the-counter

- Weaker than retinoids

- Work on mild-to-moderate acne to some degree

- Mainly used for cosmetic purposes, particularly anti-aging

Retinoids:

- Available only as a prescription (except for 0.1% adapalene)

- Stronger than retinol

- Work on mild-to-moderate acne to some degree (more than retinol)

- Mainly used as anti-acne treatments, but often prescribed for cosmetic purposes as well, particularly anti-aging

The Science

Retinol and retinoids are compounds derived from vitamin A that are often confused with one another because they sound similar and are frequently used to treat the same skin conditions. Both retinol and retinoids are usually formulated into topical products, so for the purposes of this article, I’ll discuss the topical versions of these compounds.

Research investigating the effectiveness of retinol and retinoids has shown that both are effective for treating skin ailments like mild-to-moderate acne, rosacea, psoriasis, and skin cancers, as well as helping fade stretch marks, aiding in wound healing, and combating aging.1-9 However, retinol and retinoids come from different sources, have distinct chemical structures, and work differently in the skin, and ultimately, even though both work, retinol is weaker. Let’s have a look at how they differ.

Retinol (over-the-counter): An inactive form of vitamin A. The body must convert retinol into its active form after it is applied to the skin. It is available in many over-the-counter anti-aging creams and some over-the-counter acne treatments.

Retinoids (prescription): An active form of vitamin A. It is available in the prescription medications tretinoin, adapalene, and tazarotene. (One exception–the lowest 0.1% strength form of adapalene is now available in over-the-counter products as well.)

Expand to learn about sources of retinol & retinoids

Retinol: Retinol is a type of vitamin A that living organisms create through eating fruits, vegetables, and certain animal proteins. Scientists can also create retinol in a laboratory setting.

Retinoids: Specific derivatives of vitamin A that are created in a laboratory setting.

However, classification of retinol and retinoids leads to confusion because both have similar chemical structures, and are therefore grouped into a large family of chemical compounds termed retinoids. Consequently, scientists classify retinol as a retinoid because its chemical structure is similar to that of other substances in the retinoid family. However, retinol is a unique member of the retinoid family because it is naturally created.10-13 For the purposes of clarity, this article defines retinol as the vitamin A substance that is produced naturally and retinoids as all members of the retinoid family that scientists synthesize in a laboratory.

Expand to learn about creation and synthesis of retinol & retinoids

Retinol: Creation occurs in the body when the liver converts beta-carotene, or other similar chemicals found in colorful fruits and vegetables, into retinol after consumption. The liver can also convert animal sources of retinol, including organ meat like the kidney or liver, and also eggs, which contain chemicals like retinyl ester, into retinol.13

Retinoids: For retinoids, scientists begin synthesis with a glucuronidation molecule isolated from animal liver. After isolation, scientists then chemically modify and convert glucuronidation into the desired retinoid chemical compound.14,15 After the chemical modification process is complete, pharmaceutical companies add the synthesized retinoid to creams, gels, or other solutions which doctors can then prescribe to patients to treat various skin conditions.

Expand to learn how retinol & retinoids work inside skin cells

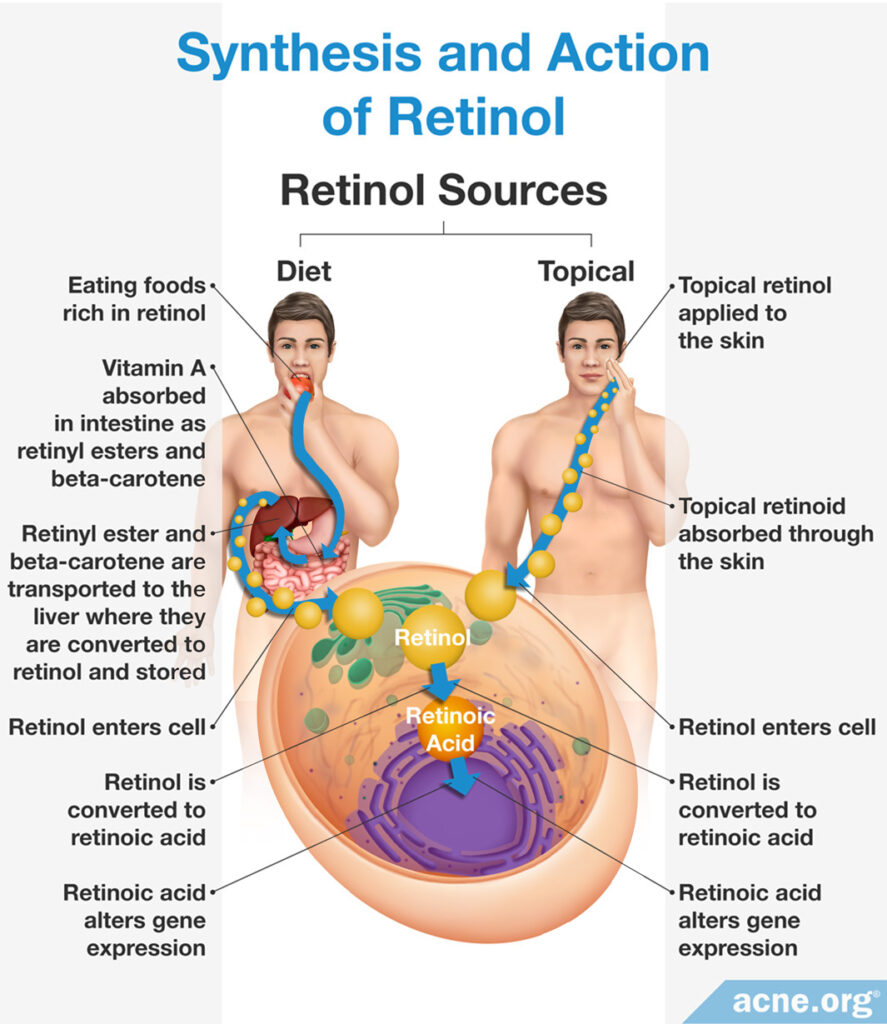

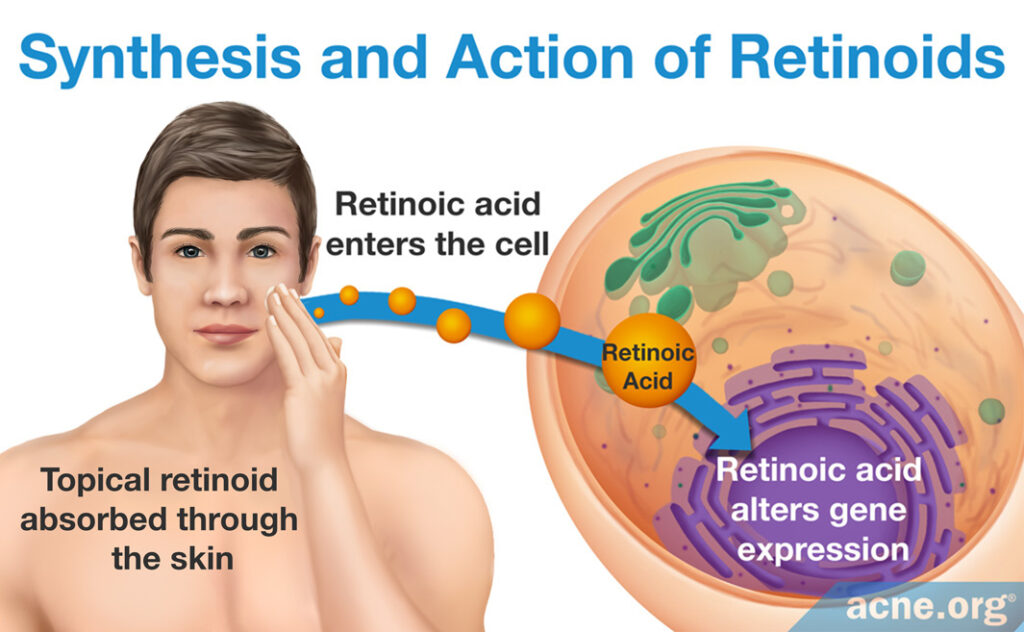

In order to treat skin conditions, both retinol and retinoids must be introduced into skin cells. How retinol or retinoids enter skin cells depends on its source.

Retinol: In response to bodily signals, retinol synthesized and stored in the liver is released into the bloodstream in order to travel to skin cells. Skin proteins on the surface of the cell absorb retinol once it arrives. If a person applies topical skincare products containing retinol, skin proteins on the surface of the cell absorb the substance. Once inside the cell, retinol signals for and alters the expression of certain genes, which provides the associated therapeutic effects.

Retinoids: When a person applies topical skincare products containing retinoids, skin cells absorb the retinoids. Once inside the cell, much like retinol, retinoids signal for and alter the expression of certain genes, which provides the associated therapeutic effects. The difference in the mechanism of action between retinol and retinoids is largely due to the specificity of each for a different set of skin proteins, which triggers difference in skin gene expression.1,13,16-26

Expand to learn about the chemical structural differences of retinol & retinoids

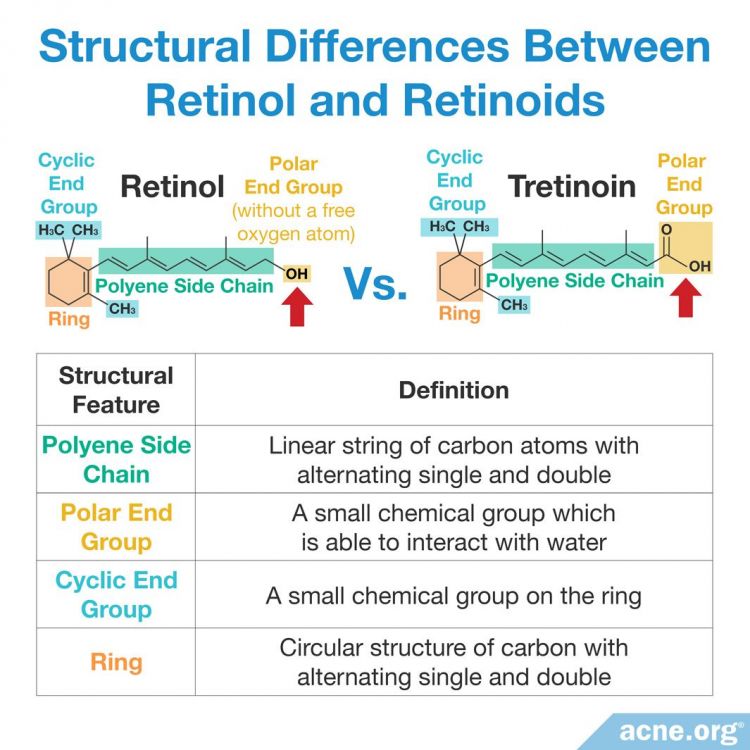

Like all other organic (carbon-containing) molecules, the chemical structure of the family of retinoids–including retinol–contains a foundation of carbon atoms. To form organic chemicals, multiple carbon atoms are bonded together to form linear strings or circular rings, which provide the molecule with different functions.4,27,28

Retinol: Contains four specific molecular structural features. However, it lacks a single oxygen atom on the structural feature known as the polar end group, which is present in all other retinoids.

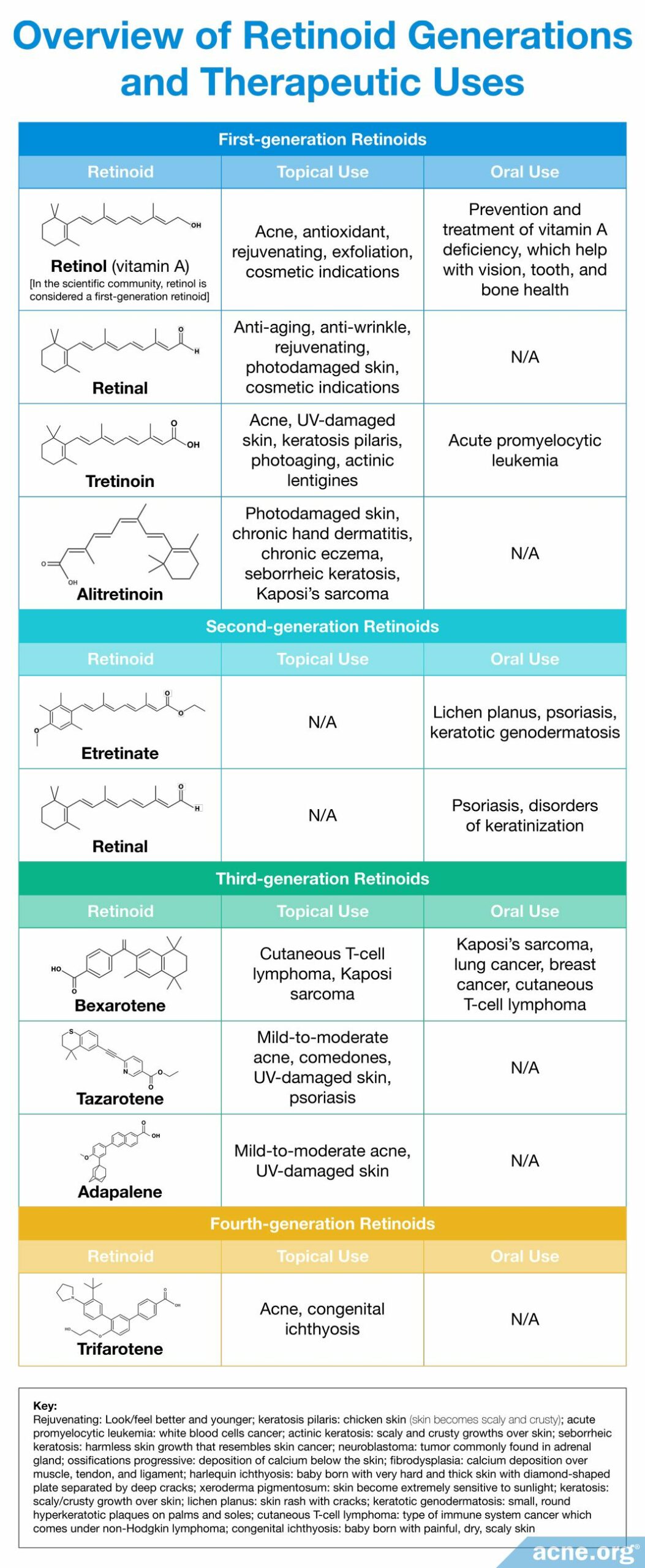

Retinoids: Contain the same four specific molecular structural features which, when altered, allow for the creation of new retinoid derivatives. Over time, scientists have slightly altered these foundational elements in order to create new laboratory-synthesized retinoids with improved efficacy. Four generations of retinoids have been created based on their molecular structure and time of discovery.4,12,13,29,30 Each generation differs slightly in structural changes within one or more of the foundational elements that provide it with an altered mechanism of action and therapeutic effect.2 For example, when scientists altered the positions of the single and double bonds within the polyene side chain, it allowed for retinoids to bind to a more diverse set of skin proteins and differentially affect skin gene expression.4,27,28 The chemical structures and therapeutic effects of different synthesized retinoids are summarized below.

Side Effects of Retinol & Retinoids

As with any medication, patients using retinol or retinoids to treat various skin conditions can develop side effects.

Retinol: People using topical retinol treatments can develop skin irritation like itching, burning, and rashes.

Retinoids: Patients applying topical retinoid treatments can develop irritation, scaling, and redness on the skin. For retinoid therapy, a medical professional monitors patients, and therefore controls or prevents side effects by altering the type or dosage of the retinoid therapy.4,31-34

References

- Elewa, R. M. & Zouboulis, C.C. Vitamin A and the skin. In Nutrition and Skin: Lessons for Anti-Aging, Beauty and Healthy Skin 7 – 23. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9781441979667

- Zouboulis, C. C. Retinoids – which dermatological indications will benefit In the near future? Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol 14, 303 – 315 (2001). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11586072/

- Rathi, S. K. Acne vulgaris treatment: The current scenario. Indian J Dermatol 56, 7 – 13 (2011). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3088940/

- Mukherjee, S. et al. Retinoids in the treatment of skin aging: an overview of clinical efficacy and safety.Clinical Interv Aging l, 327 – 348 (2006). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2699641/

- Rittie, L., Fisher, G. J. & Voorhees, J. J. Retinoid therapy for photoaging. Springer Berlin Heidelberg 143 – 153. http://eknygos.lsmuni.lt/springer/426/143-156.pdf

- Brandaleone, H. & Papper, E. The effect of the local and oral administration of cod liver oil on the rate of wound healing in vitamin A-deficient and normal rats. Ann Surg 114, 791 – 798 (1941). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1385826/

- Ehrlich, H. P. & Hunt, T. K. Effects of cortisone and vitamin A on wound healing. Ann Surg. 167, 324 – 328 (1968). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5638517/

- Bollag, W. & Holdener, E. E. Retinoids in cancer prevention and therapy. Ann Oncol 3, 513 – 526 (1992). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1498071/

- Ross, C. Retinoid production and catabolism: Role of diet in regulating retinol esterification and retinoic acid oxidation. J Nutr 133, 291s – 296s (2003). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12514312/

- Roos, T. C. et al. Retinoids metabolism in the skin. American Soc Pharmacol Exp Ther 50, 315 – 329 (2012). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9647871/

- Rastinejad, F. Retinoids. Medical Pharmacology Faculty University of Virginia. 1 – 10. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.655.2386&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Ishida, S. et al. Clinically potential subclasses of retinoid synergists revealed by gene expression profiling. Mol Cancer Ther 2, 49 – 58 (2003). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12533672/

- Vitamin A (retinol) (Mayo Clinic, 2013). https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements-vitamin-a/art-20365945

- Vitamins and minerals (National Health Service UK). https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vitamins-and-minerals/

- Jensen, N. C. & Bobroff, L. B. Facts about Vitamin A. Report No. FCS8639, (University of Florida IFAS Extension). https://journals.flvc.org/edis/article/download/116006/114200

- O’Byrne, S. M. & Blaner, W. S. Retinol and retinyl esters: biochemistry and physiology. J Lipid Res 54, 1731 – 1743 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3679378/

- Raverdeau, M. & Mills, K. H. Modulation of T cell and innate immune responses by retinoic acid. J Immunol 192, 2953 – 2958 (2014). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24659788/

- Blomhoff, R. & Blomhoff, H. K. Overview of retinoid metabolism and function. J Neurobiol 66, 606 – 630 (2005). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16688755/

- Adamo, A. et al. Mode of action of retinol. J Biol Chem 256, 3279 – 3287 (1979). https://www.jbc.org/content/254/9/3279.full.pdf

- Kafi, R. et al. Improvement of naturally aged skin with vitamin A (retinol). JAMA Dermatol 143, 606 – 612 (2007). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17515510/

- Omori, M. & Chytil, F. Mechanism of vitamin A action. J Biol Chem 257, 14370 – 14374 (1982). https://www.jbc.org/content/257/23/14370.full.pdf

- Fisher, G. J. & Voorhees, J. J. Molecular mechanisms of retinoid actions in skin. FASEB J 10, 1002 – 1013 (1996). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8801161/

- Fisher, G. J., Datta, S. C. & Voorhees, J. J. Retinoic acid receptor-γ in human epidermis preferentially traps all-trans retinoic acid as its ligand rather than 9-cis retinoic acid. J Investig Dermatol 110, 297 – 300 (1997). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022202X15400363

- Tsukada, M. et al. 13-cis retinoic acid exerts its specific activity on human sebocytes through selective intracellular isomerization to all-trans retinoic acid and binding to retinoid acid receptors. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology 115, 321 – 327 (2000). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10951254/

- Rolewski, S. L. Clinical review: Topical retinoids. Dermatology Nurs 15, (2003). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14619325/

- Decker, A. & Graber, E. M. Over-the-counter acne treatments: A review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 5, 32 – 40 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3366450/

- Fuse809. (ed Structure of Retinoids) (Wikipedia, 2014). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Retinoid

- Ishida, S. et al. Class prediction of synthetic retinoids and synergists. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2, 49-58 (2003). https://mct.aacrjournals.org/content/molcanther/2/1/49.full.pdf

- Therapeutic Class Review: topical retinoids (University of Massachusetts Medical School, 2012). https://www.medicaid.nv.gov/Downloads/provider/Topical Retinoids 2012 12.pdf

- Tan, J. & Miklas, M. A novel topical retinoid for acne: Trifarotene 50 μg/g cream. Skin Therapy Lett. 25, 1‐2 (2020). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32196146/

- Kang, S. et al. Application of retinol to human skin in vivo induces epidermal hyperplasia and cellular retinoid binding proteins characteristic of retinoic acid but without measurable retinoic acid levels or irritation. J Investig Dermatol 105, 549 – 556 (1995). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7561157/

- Chien, A. L. et al. Treatment of acne in pregnancy. J Am Board Fam Med 29, 254 – 262 (2016). https://www.jabfm.org/content/29/2/254

- Ehrlich, S. D. Vitamin A (Retinol) (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 2020). https://www.mountsinai.org/health-library/supplement/vitamin-a-retinol

- Tantibanchachai, C. Retinoids as teratogens. In The Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2014). https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/retinoids-teratogens