Information on this Outdated and, at Best, Temporary Acne Treatment

The Essential Info

Antibiotics should only be used for a maximum of 3 months and they work to a moderate degree for only about 1/2 of people with acne. When they do work at all, they provide only temporary relief. They do not dramatically clear the skin on their own, and must always be combined with other treatments.

Perhaps even more concerning is the fact that antibiotics create strains of resistant bacteria that can last a lifetime and can be spread from person to person. For all of these reasons, doctors are prescribing antibiotics for acne less than in previous decades.

My Experience: When I was seeing doctors for my acne in high school and college, I was prescribed antibiotics, both oral and topical. The oral antibiotics did nothing for my acne and upset my stomach quite a bit. The topical antibiotic also did nothing. In fact, my acne was at its all time worst when I was religiously using clindamycin (a topical antibiotic). When I look back, I feel disappointed in those doctors for prescribing antibiotics, but I also understand that they really didn’t know what else to do. Luckily these days there are better treatments, and doctors are prescribing antibiotics less often.

The Science

- Why Antibiotics Don’t Work as Well as They Should

- Side Effects

- What to Do If Your Doctor Suggests Antibiotics for Your Acne

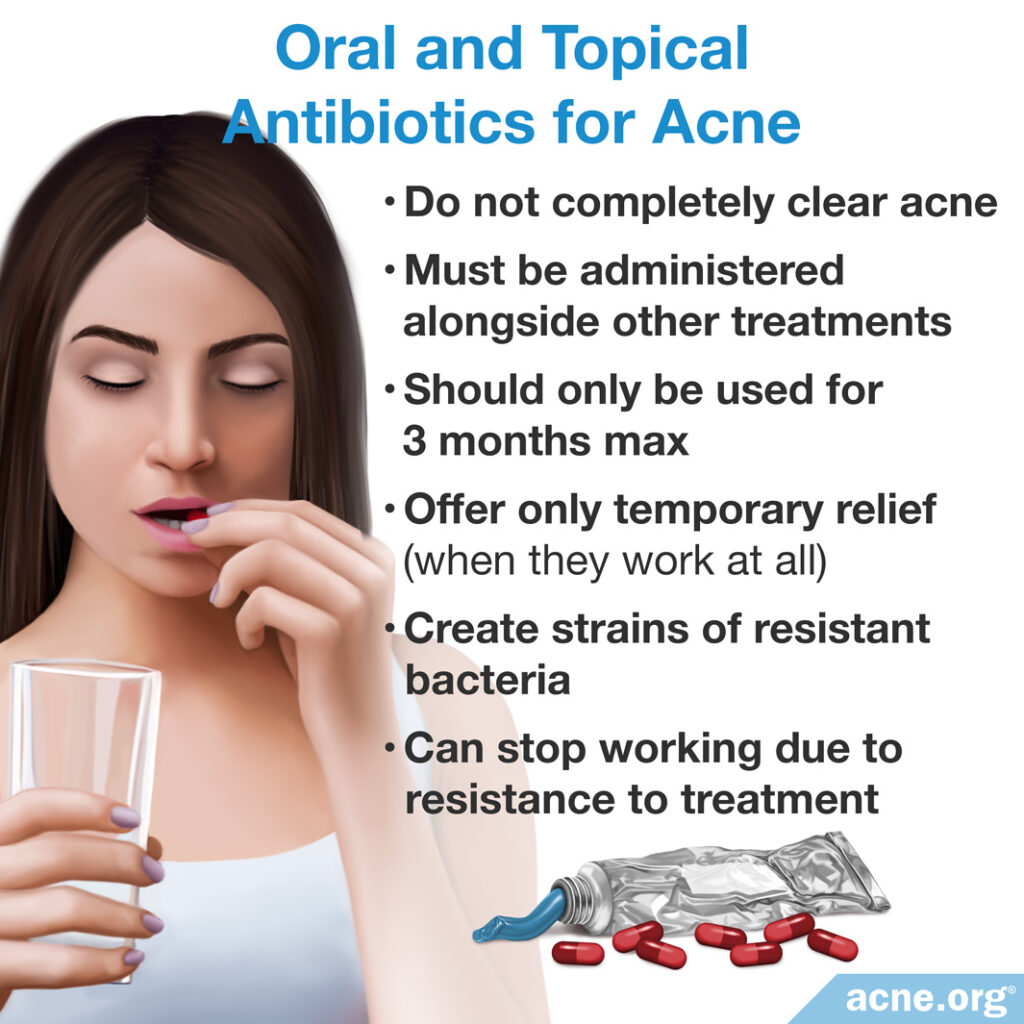

Oral and topical antibiotics have been a mainstay of acne treatment for decades, despite the fact that they:

- Never completely clear acne.

- Only work for about 1/2 of people with acne.

- Should only be used for a maximum of 3 months, thus only offering the hope of temporary relief.

- Must always be administered alongside topical treatments in order to limit their ability to create resistant strains of bacteria that can follow a user for the rest of their lives.1-6

- Come with a myriad of side effects.

As time marches on, however, both physicians and patients are realizing the limited effectiveness and potential drawbacks of antibiotics, and they are being prescribed less often than in the past.

Here’s how oral and topical antibiotics differ when it comes to treating acne:

- Oral antibiotics help kill acne bacteria (C. acnes) in people who are not resistant to their effects and also help reduce inflammation.7-10

- Topical antibiotics do not kill acne bacteria, but do help reduce inflammation.11

Note: Oral and topical antibiotics should never be used at the same time.

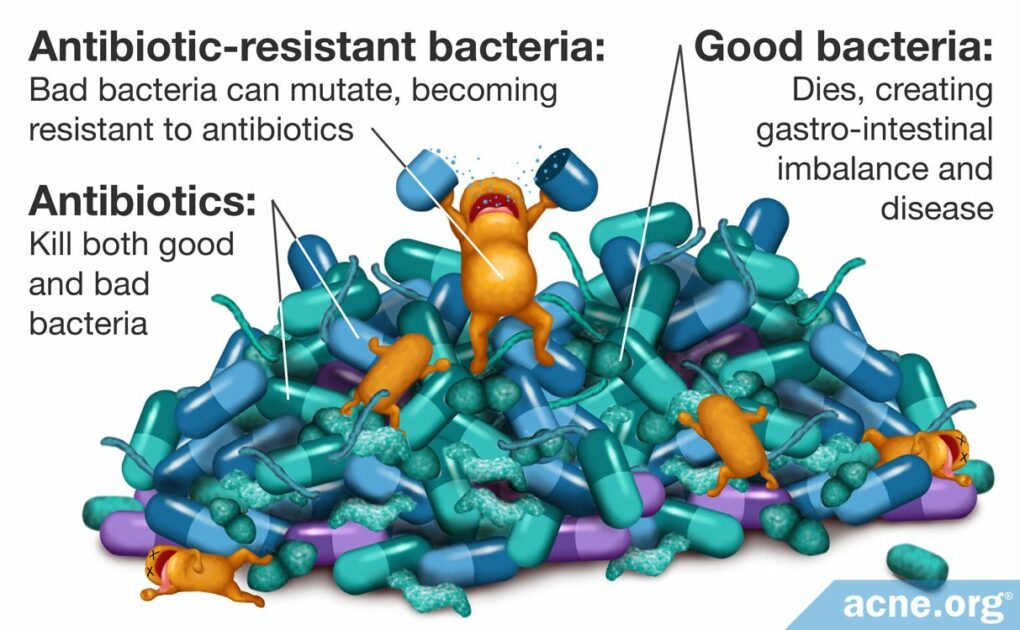

Why Antibiotics Don’t Work as Well as They Should

It has long been noted that antibiotics only work for about half of the population, and produce only moderate effectiveness.12 When they do help, they often only work for a short period of time. This is because acne tends to “get used to” both oral and topical antibiotic treatments and become resistant to it.7,13

As more research comes to light, it appears antibiotics are not helping clear acne as well as they once did. Researchers theorize this may be directly related to increased bacterial resistance across the entire population.13

It has become accepted practice that antibiotics must always be used in conjunction with other topical treatments because this helps reduce the chance for resistance, and because antibiotics do not work well enough on their own.

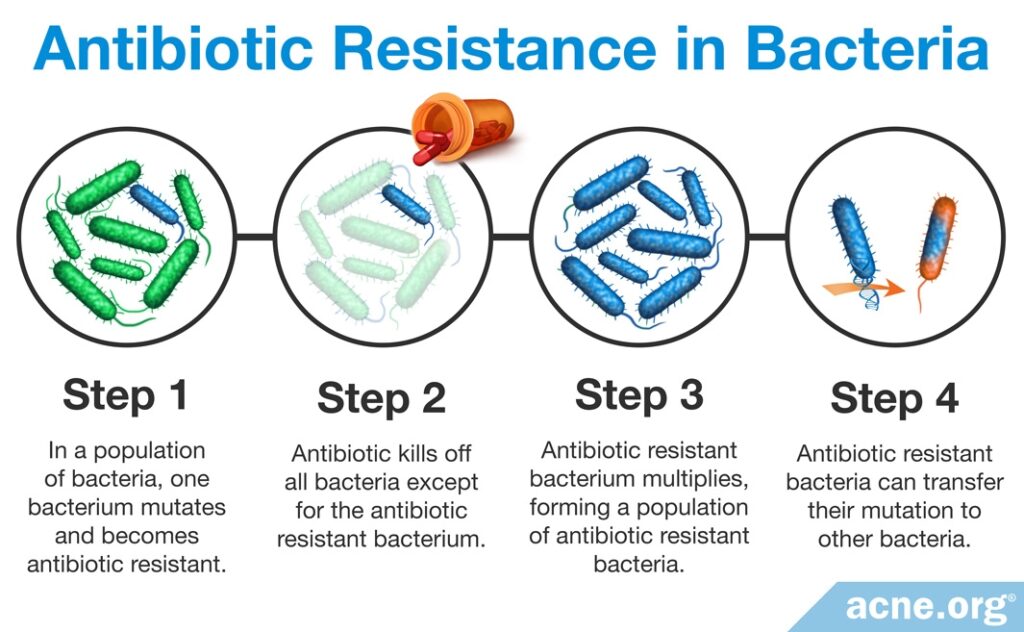

The following illustration shows how antibiotic resistance occurs.

A large study conducted by British Journal of Dermatology studied 4274 acne patients and found that since 1991 an average of 51% of patients harbored colonies of resistant bacteria.14

Other studies have shown similar levels of antibiotic resistant acne bacteria.15-20

Interestingly, researchers are finding similar levels of resistance in both patients treated with antibiotics and those untreated as well, although those untreated have somewhat lower levels of resistance.21 This is because it is quite easy to pass antibiotic resistant strains of bacteria to people close to you.22 All you have to do is touch your skin and then touch someone else. Voila.

All antibiotics are well known to create resistant strains of bacteria, and as mentioned, these resistant strains of bacteria now colonize upwards of half of the population.26-27 In response to the increasing threat of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, the World Health Organization (WHO) has issued guidelines to limit the use of antibiotics. However, doctors are lagging behind in following these recommendations.28

How do bacteria achieve such a feat? Bacteria are amazing tiny single celled creatures that were among the first living things on the earth. They have evolved to:

- Mutate their genes.

- Work together to produce a coating around themselves called “biofilms.”8,10,23-25

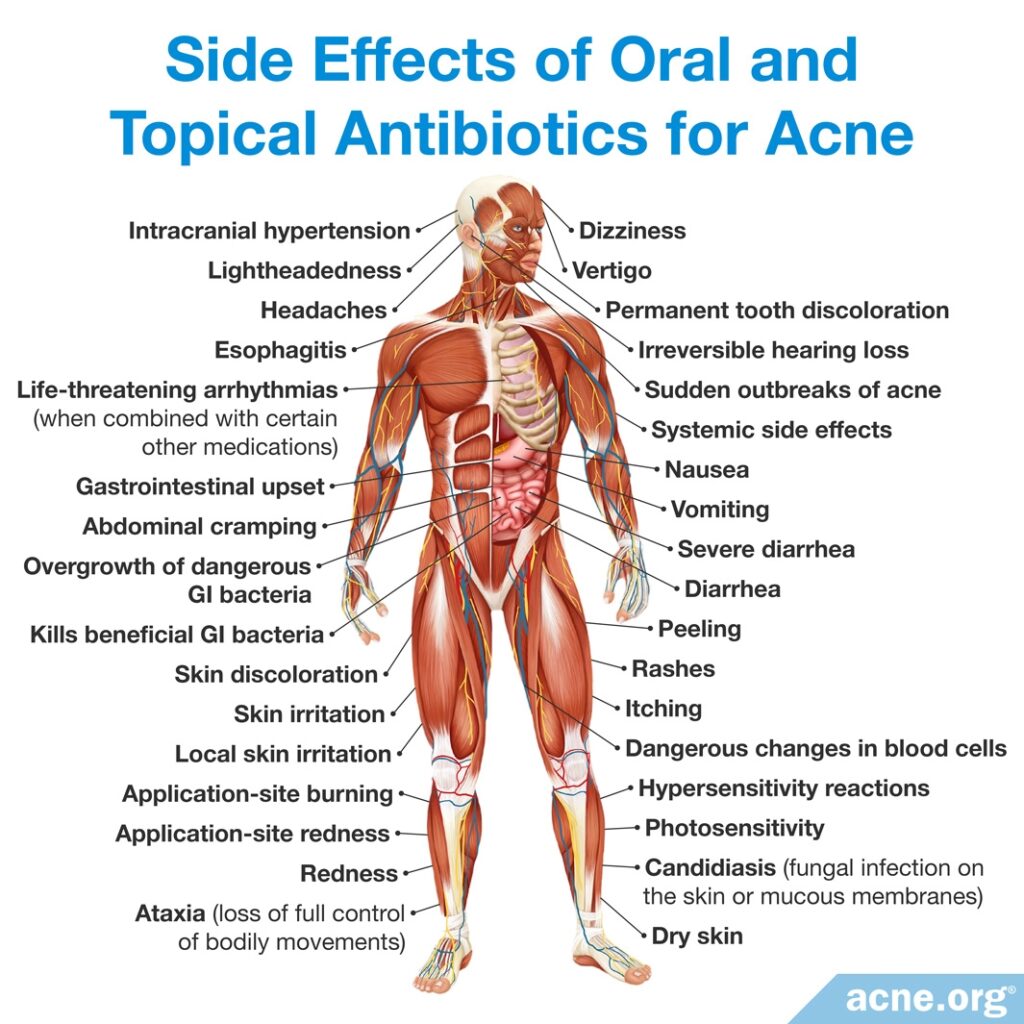

Side Effects

It is important to note that antibiotics have many side effects beyond creating resistant bacteria. If antibiotics worked well for acne, some of these side effects might be worth it, but when you consider how poorly they work for acne, the risk/reward of antibiotics starts to feel more heavy on the risk side.

Side effects of oral antibiotics

Oral antibiotics have more side effects than topical antibiotics and commonly cause:

- Gastrointestinal disorders (diarrhea, nausea, stomach cramps).

- Skin reactions (rash).

- Neurological problems (dizziness, vertigo).

- Photosensitivity (increased sensitivity to the sun).

Less frequent side effects include:

- Permanent bluish-gray discoloration of the skin.

- Permanent yellow/gray/brown discoloration of teeth.

- Sudden outbreaks of acne–exactly what we don’t want!

In rare cases, oral antibiotics can cause:

- Auto-immune diseases (i.e. lupus).

- Irreversible hearing loss.

- Heart problems which can lead to death.29-32

This is far from a full list of side effects. For a full list, click here.

Side effects of topical antibiotics

Topical antibiotics have fewer side effects but can also be absorbed through the skin and into the body and cause:

- Gastrointestinal problems.

Upon application, topical antibiotics commonly cause:

- Peeling.

- Skin irritation, including redness, dryness, and burning.22,29

Infections due to overuse of oral and/or topical antibiotics

Some beneficial bacteria in the body limit the spread of harmful bacteria. Because oral and topical antibiotics can kill these beneficial bacteria, they place the person at risk of infections unrelated to acne, such as throat infections. Some research suggests that the overgrowth of harmful bacteria, including antibiotic-resistant bacteria, can even spread to other individuals in the same household.28,33,34

Pregnancy: Neither oral nor topical antibiotics should be used while attempting to become pregnant, while pregnant, or while breast feeding unless specifically directed by a physician.29

What to Do If Your Doctor Suggests Antibiotics for Your Acne

First, ask her why she wants you to do this and if there are other options you can try instead.

If you are prescribed antibiotics from a doctor, do not stop your course before speaking with her about it since this can make it more likely that you will create resistant strains of bacteria that will be with you for the rest of your life.

References

- Costa, C. S. & Bagatin, E. Evidence on acne therapy. Sao Paulo Med. J. 18, 193-197 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23903269

- Leyden, J. J. Antibiotic resistance in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 73(6 Suppl), 6-10 (2004). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15228128

- Leyden, J. J., Wortzman, M. & Baldwin, E. K. Antibiotic-resistant Propionibacterium acnes suppressed by a benzoyl peroxide cleanser 6%. Cutis. 82, 417-21 (2008). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19181031

- Leyden, J. J. Effect of topical benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin versus topical clindamycin and vehicle in the reduction of Propionibacterium acnes. Cutis. 69, 475-480 (2002). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12078851

- Worret, W. I. & Fluhr, J. W. [Acne therapy with topical benzoyl peroxide, antibiotics and azelaic acid]. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 4, 293-300 (2006). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16638058

- Kircik, L. H. Ther role of benzoyl peroxide in the new treatment paradigm for acne. J. Drugs Dermatol. 12, s73-76 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23839205

- Leyden, J. & Levy, S. The development of antibiotic resistance in Propionibacterium acnes. Cutis. 67(2 Suppl), 21-24 (2001). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11236211

- Leyden, J. J. Current issues in antimicrobial therapy for the treatment of acne. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 15 Suppl 3, 51-55 (2001). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11843235

- Ochsendorf, F. Systematic therapy of acne vulgaris. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges.4, 828-841 (2006). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17010172

- Thevarajah, S., Balkrishnan, R., Camacho, F. T., Feldman, S. R. & Fleischer, A. B. Jr. Trends in prescription of acne medication in the US: shift from antibiotic to non-antibiotic treatment. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 16, 224-228 (2005). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16249143

- Dreno, B. Topical antibacterial therapy for acne vulgaris. Drugs. 64, 2389-2397 (2004). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15481998

- Ozolins, M. et al. Randomised controlled multiple treatment comparison to provide a cost-effectiveness rationale for the selection of antimicrobial therapy in acne. Health Technol. Assess. 9, iii-212 (2005). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15588555

- Eady, A. E., Cove, J. H. & Layton, A. M. Is antibiotic resistance in cutaneous propionibacteria clinically relevant? : implications of resistance for acne patients and prescribers. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 4, 813-831 (2003). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14640775

- Coates, P. et al. Prevalence of antibiotic-resistant propionibacteria on the skin of acne patients: 10-year surveillance data and snapshot distribution study. Brit. J. Dermatol. 146, 840-848 (2002). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04690.x

- Luk, N. M. et al. Antibiotic-resistant Propionibacterium acnes among acne patients in a regional skin centre in Hong Kong. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 27, 31-36 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22103749

- Nakase, K. Nakaminami, H., Noguchi, N., Nishijima, S. & Sasatsu, M. First report of high levels of clindamycin-resistant Propionibacterium acnes carrying erm(X) in Japanese patients with acne vulgaris. J. Dermatol. 39, 794-796 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22142418

- Narahari, S., Gustafson, C. J. & Feldman, S. R. What’s new in antibiotics in the management of acne? G. Ital. Dermatol. Venereol. 147, 227-238 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22648324

- Chon, S. Y. et al. Antibiotic overuse and resistance in dermatology. Dermatol. Ther. 25, 55-69 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22591499

- Toyne, H., Webber, C., Collignon, P., Dwan, K. & Kljakovic, M. Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes) resistance and antibiotic use in patients attending Australian general practice. Australas. J. Dermatol. 53, 106-111 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22571557

- Dreno, B., Reynaud, A., Moyse, D., Habert, H. & Richet, H. Erythromycin-resistance of cutaneous bacterial flora in acne. Eur. J. Dermatol. 11, 549-553 (2001). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11701406

- Del Rosso, J. Q., Leyden, J. J., Thiboutot, D. & Webster, G. F. Antibiotic use in acne vulgaris and rosacea: clinical considerations and resistance issues of significance to dermatologists. Cutis. 82(2 Suppl 2), 5-12 (2008). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18924545

- Oudenhoven, M. D., Kinney, M. A., McShane, D. B., Burkhart, C. N. & Morrell, D. S. Adverse Effects of Acne Medications: Recognition and Management. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 16, 231-242 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25896771

- Ishida, N. et al. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Propionibacterium acnes isolated from patients with acne vulgaris. Microbiol. Immunol. 52, 621-624 (2008). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19120976

- Ross, J. I. et al. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of antibiotic-resistant Propionibacterium acnes isolated from acne patients attending dermatology clinics in Europe, the U.S.A., Japan and Australia. Br. J. Dermatol. 144, 339-346 (2001). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11251569

- Coates, P. et al. Efficacy of oral isotretinoin in the control of skin and nasal colonization by antibiotic-resistant propionibacteria in patients with acne. Br. J. Dermatol. 153, 1126-1136 (2005). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16307647

- Eady, E. A., Gloor, M. & Leyden, J. J. Propionibacterium acnes resistance: A world wide problem. Dermatology. 206, 11-16 (2003). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12566805

- Ross, J. I. et al. Antibiotic-resistant acne: lessons from Europe. Br. J. Dermatol. 148, 467-478 (2003). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12653738

- 67th World Health Assembly. WHA67.25. Antimicrobial Resistance. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_R25-en.pdf

- Tripathi, S. V. et al. Side effects of common acne treatments. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 12, 39-51 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23163336

- McMullan, B. J. & Mostaghim, M. Prescribing azithromycin. Australian Prescriber Web. 38, 87-90 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26648627

- Turowski, C. B. & James, W. D. The Efficacy and Safety of Amoxicillin, Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole, and Spironolactone for Treatment-Resistant Acne Vulgaris. Adv. Dermatol. 23, 155-163 (2007). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18159900

- Gillies M, et al. Common harms from amoxicillin: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials for any indication. CMAJ. 187, E22-E31 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25404399

Further reading:

- Bojar, R. A. & Holland, K. T. Acne and Propionibacterium acnes. Clin. Dermatol. 22, 375-379 (2004). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15556721

- Del Rosso, J. Q. Selection of therapy for acne vulgaris: balancing concerns about antibiotic resistance. Cutis. 82(5 Suppl),12-16 (2008). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19202773

- Dr Kno B. General antibiotic therapy in acne. [Article in French] La Revue du praticien. 52, 841-843 (2002). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/11319570_General_antibiotic_therapy_in_acne

- Garner, S. E., Eady, E. A., Popescu, C., Newton, J. & Li, W. A. Minocycline for acne vulgaris: efficacy and safety. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1, CD002086 (2003). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12535427

- Leyden, J. J., Del Rosso, J. Q. & Webster, G. F. Clinical considerations in the treatment of acne vulgaris and other inflammatory skin disorders: a status report. Dermatol. Clin. 27, 1-15 (2009). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18984363

- McInturff, J. E. et al. Granulysin-derived peptides demonstrate antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects against Propionibacterium acnes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 125, 256-263 (2005). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16098035

- Mills, O. Jr, Thornsberry, C., Cardin, C. W., Smiles, K. A. & Leyden, J. J. Bacterial resistance and therapeutic outcome following three months of topical acne therapy with 2% erythromycin gel versus its vehicle. Acta Derm. Venereol. 82, 260-265 (2002). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12361129

- Oprica, C. et al. Antibiotic-resistant Propionibacterium acnes on the skin of patients with moderate to severe acne in Stockholm. Anaerobe. 10, 155-164 (2004). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16701513

- Qureshi, A. Survival of antibiotic-resistant Propionibacterium acnes in the environment. 14th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2004, Prague, poster presentation. Abstract number: 902_p818. Accessed online on the 8th of April, 2009.

- Zouboulis, C. C. & Piquero-Martin, J. Update and future of systemic acne treatment. Dermatology. 206, 37-53 (2003). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12566804